There is nothing the matter with the movies that cannot be remedied. This is indeed fortunate–for the movie has earned an important place in the life of the American public. No one will deny that motion pictures have been helpful, instructive, and entertaining. No one doubts that they can be a great influence for good–or evil. And everyone knows they are too big to be ignored. They have assumed such importance as to incur a proportionate responsibility. And yet those entrusted with their development choose to close their eyes to the writing on the wall. The principal trouble with the motion picture today is that it is an industry, not an art. It has been too highly commercialized for its own good. Of course, the businessperson is necessary to the motion picture, but not to the exclusion of the artist. It is right and good that Fords and locomotives and adding machines and safety razors and lead pencils shall be standardized and turned out according to hard and fast specifications–and that quantity production shall cut down overhead. It is also good business that the distributing station be standardized and handle the usual full line of equipment at standard prices. But those methods are bad medicine for motion pictures. The film made to the dollar-ruled specification, turned out on a quantity production basis, added to the cut-and-dried program, and then released throughout the trust-controlled theatres is, without doubt, a specimen of efficient industrial production–but as an artistic entertainment it is a sad failure. No one doubts that pictures can be produced under this highly efficient business method much cheaper and faster than by the old “hit-or-miss” artistic way–and that these pictures can net their producers and distributors a much larger return per dollar invested than those handicapped by artistic requirements. But, after all, what are you spending your money in your local moving-picture theatre for? To see artistic, fascinating pictures or to build fortunes for those in control of the industry? There the heart of the problem is exposed–the average motion picture is made to fatten purses, not to entertain the public. Commercial motion pictures have their rightful usage, as have also less artistic films of entertainment, just the same as commercial art has its proper place, and commercial music and jazz, and advertising and cheap vaudeville and burlesque. But how would you like to discover the powers that be insisting that you must take your art and your music and your literature “according to our program.” Suppose you went to the Grand Opera and heard a little factory-produced opera, then a little jazz and then a half hour of song “plugging” flavored with ten minutes of Galli-Curci or Chaliapin singing a nursery rhyme. Or suppose when you purchased a set of Shakespeare you found every other page devoted to advertising or publicity writing or that your evening to Ethel Barrymore was four-fifths taken up by an act of cheap melodrama, a little burlesque, a bit from the minstral and an acrobatic squad. Suppose that when you attempted to buy pictures for your home you discovered they could only be shown in connection with commercial drawings. Yet you get just about such a hodgepodge when you attend a motion picture theatre running trust-controlled programs. And with the trust growing stronger every day the independent exhibitor is being driven farther and farther into the corner. All of which is very fine for efficiency and profit, but very bad for art and entertainment. In my opinion, 75 per cent of the pictures shown today are a brazen insult to the public’s intelligence. The other 25 per cent are produced by such experts as D. W. Griffith, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, the Talmadge interests–and a few other independent stars and producers who realize that the making of pictures is an art, not an industry. Such splendid features as “Broken Blossoms,” “Way Down East,” “Tolerable [sic] David,” “Little Lord Fauntleroy,” “Robin Hood,” “The Kid,” “When Knighthood was in Flower,” along with a few other productions which rank among these, have invariably been received in such a way as to prove that the American public wants and appreciates artistic productions. The next thing to do is demand them. The public always gets what it _demands_. All of these pictures were produced by independent companies who loathe to follow the factory cut-and-dried methods perfected by the picture trusts. The various stars and directors who have fought and dared to produce films of real merit are keeping faith with you in spite of the handicaps they face. They are courageously battling the interests that are monopolizing not only the production but the exhibition of motion pictures. They deserve your unqualified support. The only hope for the future of the moving picture lies with them. Support them and you will enjoy pictures made by conscientious producers, from real stories, pictures in which the artists have an opportunity to give you the best they have. Under the present system the actor is treated like a factory hand–is driven helter-skelter through a picture by a director who is afraid of the slave-driving studio manager who, in turn is spurred to increased production by producers. And these producers have but a single motive–profit. Such producers established themselves by imitating, in a superficial and insincere way, the artistic productions of D. W. Griffith, Mary Pickford and others by cashing in on their creative genius. Then they were merely parasites. Now they are infinitely worse. Instead of merely imitating, they are attempting to crush the conscientious producer. And their method of crushing is efficient–as is every other business scheme they have worked out. The blade with which they are trying to knife the producer of artistic pictures cuts two ways. First it hamstrings him and then it cuts off his lines of distribution. Process No. 1 is to discredit the stars that work with him and at the same time reduce to a minimum the value of the production on which he is working. The most efficient way to discredit stars is to make them common–to belittle their work; to prevent them from expressing their own interpretation of art; to compel them to perform poorly. Name over to yourself a dozen of your favorite stars. When you think of moving picture stars you think of them. Now suppose that eight of that dozen were hired by powerful syndicates and put to work on cheap pictures. Suppose that the pictures they made were weak and their work was unconvincing. Suppose each of them made four pictures, or even six or ten pictures, to every picture one of the other four made. In other words, suppose that of every ten pictures featuring your favorite stars nine were weak and and the stars’ work most disappointing. Wouldn’t you begin to feel that, after all, it was not the star but the picture that counted? And the method of discrediting artistic feature pictures is as simple. D. W. Griffith produces a marvelous spectacle–the work of countless months of time and the genius of true artists. It impresses you mightily. You must see the next spectacle of that kind when it is released. So, the “industrial” producers figure. Before D. W. Griffith can produce another masterpiece, they flood the theatres with dozens of cheap imitations, each heralded as the peer of Griffith’s best work. So grossly are they misrepresented, so flagrantly are they mis-advertised and so miserably do they fall below your expectations that you naturally “swear off” spectacles for the rest of your life. “Who suffers?” The conscientious producer. No matter how good it may be his next production is almost guaranteed a failure, now. Meanwhile the imitator flits to the next artistic production and proceeds to copy it, cheaply. In doing so he shackles a star to a weak part and then rushes him through the picture, thus, killing two birds with one stone. For the public feels it has been hoodwinked by stars and features. As real stars and real productions are all the independent producer with the conscience has to offer, he suffers once again. Do you wonder then that a moving-picture actor whose hope? for the future lies in his work of today repudiates an unfair contract rather than be a party to the ruination of good pictures? That is why I have refused to work for picture butchers at $7,000 a week on cut-and-dried program features and have offered to return to work for twelve hundred and fifty dollars a week if a competent, conscientious director directs my work in worth-while features. The trusts method of curtailing the independent producer’s distribution is also very efficient. This is accomplished through its distributing mediums. Again, we find its methods twofold. They sell complete programs, a trick by which the small exhibitor must show a whole year of their pictures in order to get any at all–and then he must take the whole program, just as it is turned out of the mills. The other method is to secure interest or ownership in theatres and permit them to show only trust pictures. So, it is not always the fault of the exhibitor who runs the theatre you patronize if the ordinary program pictures you see day in, and day out are not up to your expectations. He is not to blame any more than is the artist who appears in the picture you take exception to. The poor exhibitor, in order to secure a few good pictures with box-office value, is forced to sign the trust’s entire output for the year. And so, he must contract to rent eighty-two or more pictures, though he knows full well that some will be so impossible he will have to refrain from showing them and simply pocket his loss. That is what is the matter with the movies–and that is why the American public spent only one half as much on pictures last year as they did the year before. And that is why they will spend even less next year if something is not done to remedy the situation. The American public wants good pictures and is entitled to them. The conscientious producers want to produce good pictures and should be supported in doing it. The real artist-actor wants to give you the best there is in him. In order to do this, he must be allowed to act in high-grade pictures and take sufficient time to make them. Art is the only weapon with which the conscientious producer and the artist, or star, can fight the commercialism of the trust producers. Naturally, the trust wants to discredit art and lower the public’s idea of what the standard of pictures should be. The lower the standards, the cheaper the pictures can be made, the lower the overhead, the more the profit. Now you can understand why Rudolph Valentino is not making pictures. The merciless cutting of “Blood and Sand” threw me into grave doubts. My experience in “The Young Rajah” verified my fears. I realized that I was not going to be permitted to act in real pictures or give the necessary time and study to me work. Art? What did that mean to the commercial producers? They wanted film–thousands of feet of film. And they wanted it quickly. The quicker the film was made the less the overhead, and the sooner the release. So, we hurried through. Night after night we worked–sometimes until daylight. We actually finished the picture August 10, at three in the morning. Apparently, those producers were convinced that midnight oil is conducive to genius. I’m not going to hurry through any more pictures, and I’m not going to be cast to parts that are unworthy of a novice or a worn-out ham. Other movie actors have taken this stand. Some have fallen by the way. Some have emerged victorious–Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, the Talmadge girls, and now comes Harold Lloyd. Forget Valentino and his little squabble–but keep your eyes on the independent producers and on these stars. Compare them productions with those of trust-controlled producers. Remember that your money is the deciding vote whether the independent producer prospers and gives you real pictures or whether the trust monopolizes the whole industry and feeds you what profits it best. You are to be the judge. I know what your verdict will be. I have been asked why the producers so mercilessly hacked “Blood and Sand.” When the film was completed, it went to the business office. It was measured. It was too long–the most heinous offense known to the trust–a full six hundred feet too long. Its extra length meant a little less profit. So, to the butchering rooms it went. Of course, certain parts of it could be re-acted and condensed and thus keep the continuity clear. But that meant more time, more money, and less profit. So, clip, clip, clip. And the very heart of the film was cut out. How much that saved, I do not know, but it saved money. What if the public was a little confused and disappointed here? and there? The picture would get by. Everybody knew it was good. Why quibble about a scene or two? As a matter of fact, the picture was a lot stronger than it needed to be. And making pictures too good was simply piling up trouble for the future. It was spoiling the public. The better you give them the better they want. The thing to do was to standardize picture quality. Then they wouldn’t always be demanding the world and all for the price of one admission. With that philosophy in mind, they made “The Young Rajah”–and I quit. Maybe I’m temperamental because I refuse to caper through rot on the strength of what reputaion I may have earned. But this I know–the “Rajah” picture was the first step down. After that the descent would have been steady–and not so slow, either. Maybe, it is unbusinesslike to repudiate a contract that involves you in producing films in which you cannot possibly give the public what it is paying for, and in a process of cheapening that would mark one as a puppet rather than as an actor. If it is, then I’m unbusinesslike. It just happens that I have ideals–and hopes. I am sorry I ever acted in “The Young Rajah.” I will never act in another picture like it. The public wants art in pictures, and I believe I can put it there. Doug and Mary and Charlie and D. W. have done it and I’m going to try.

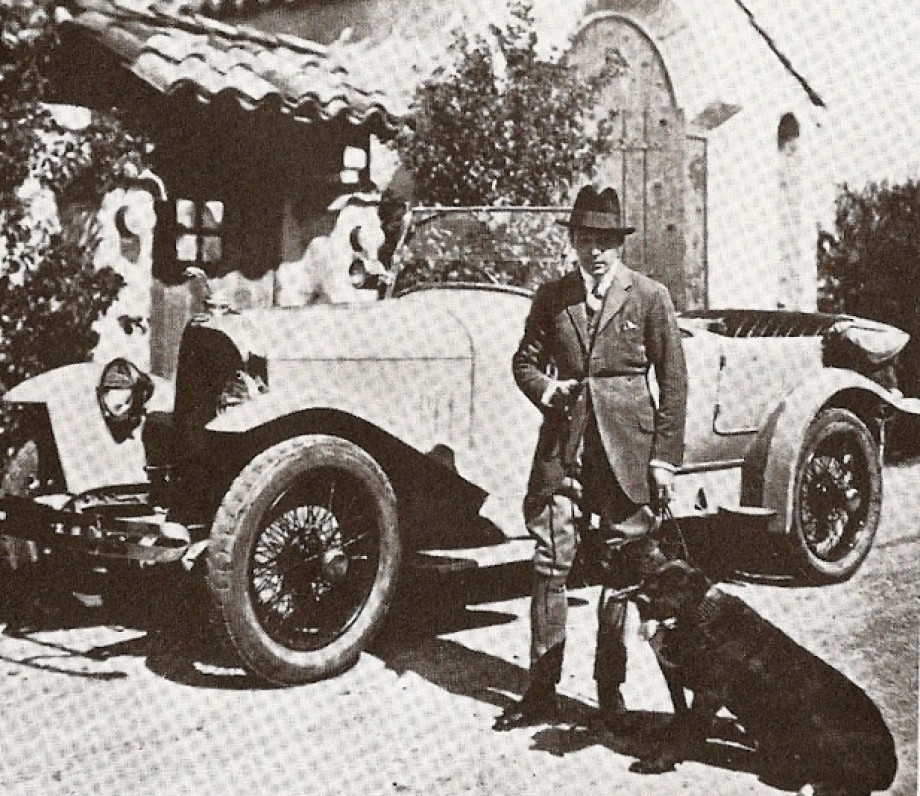

May 1923 – WHAT’S the MATTER with the MOVIES? by RUDOLPH VALENTINO

Categories: Uncategorized

Tags: Rudolph Valentino