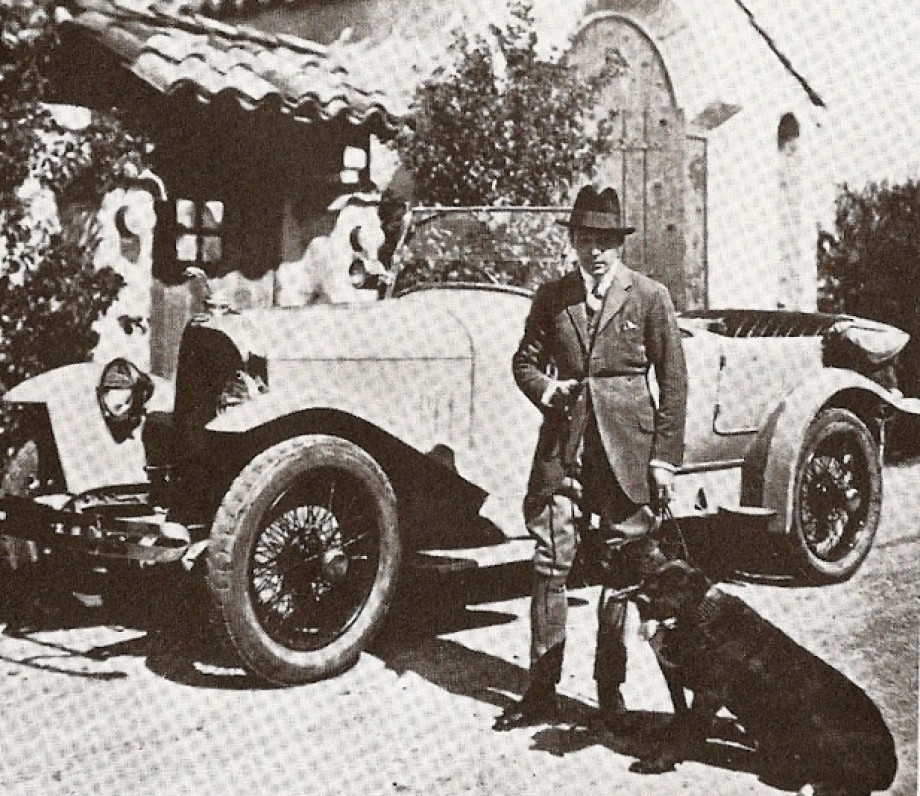

Late in 1921, our advertising copywriters took off their gloves, spit on their hands and hammered out some remarkable advice to the public. By this time all readers over forty, and doubtless most of those under, will have guessed the rest. The picture was, of course, The Sheik, with Rudolph Valentino. Top billing went not to Valentino but to the leading lady, Agnes Ayres. Valentino was twenty-six years old and had been in Hollywood for several years, dancing as a professional partner and sometimes playing bit movie parts, chiefly as a villain. Recently he had gained attention as a tango-dancing Argentine in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, made by another company. When we hired him for The Sheik we expected that he would perform satisfactorily, but little more. We certainly did not expect him to convulse the nation. Valentino was as strange a man as I ever met. Before going into his personality, however, it would seem worthwhile, taking into account what happened afterward, to review The Sheik. The story was taken from a novel of the same title by Edith M. Hull, an Englishwoman. After publication abroad the book became a sensational best seller in America. We paid $50,000 for the screen rights, a very large sum for the time, with the idea that the novel’s popularity would assure the picture’s success. The story gets underway with Diana Mayo (Agnes Ayres), a haughty English girl visiting in Biskra, remarking that marriage is captivity. Since Diana is a willful adventurous girl who dislikes the restraining hand of her cautious brother, one knows that trouble is brewing the moment she spots Sheik Ahmed Ben Hassan (Rudolph Valentino) and their eyes meet. The distance between them is roughly 150 feet, yet she quails, to use understatement, visibly. One might have thought he had hit her on the head with a thrown rock. There was nothing subtle about film emotion in those days. Learning that non-Arabs are forbidden at the fete the Sheik is holding in the Biskra Casino that night, Diana disguises herself as a slave girl and wins admission. The Sheik discovers her identity as she is about to be auctioned off along with other slaves. He allows her to escape, but later that night appears under her window singing “I’m the Sheik of Araby, Your love belongs to me. At night when you’re asleep into your tent I creep. Valentino moved his lips hardly at all when he sang. As a matter of fact his acting was largely confined to protruding his large, almost occult eyes until vast areas of white were visible, drawing back the lips of his wide sensuous mouth to bare his gleaming teeth, and flaring nostrils. But to get back to the film story. Next day, the Sheik attacks Diana’s caravan and packs her off to the desert oasis camp. Though he regards her as his bride, she fends off his advances. Yet it is soon apparent that she is falling in love with him. After a week of virtual slavery Diana begins to like it at the camp. Then she learns that Raoul de Saint Hubert, a French author and friend of the Sheik is coming to visit. Ashamed to be found in her slave like condition by a fellow European, Diana stampedes her guard’s horse while riding in the desert and makes a dash for freedom. Her horse breaks a leg and she staggers across the sand toward a distant caravan. This is the caravan of the dread bandit Omair (Walter Long). Omair makes her a captive for plainly evil reasons. But soon the Sheik having been informed of Diana’s escape by the stampeded guard, attaches the caravan and rescues her. The French author (Adolph Menjou) rebukes the Sheik for what seems to him a selfish attitude toward the girl. Next day while Diana and the Frenchman are riding in the desert, Omair swoops down, wounds the author, and carries the girl off to his strong-hold. The Sheik gathers his horsemen and rides to the rescue. Meanwhile at the strong-hold, Omair pursues the “white gazelle” as he calls Diana, around and around a room in his harem house. One of the bandit’s wives is fed up with him, has advised Diana to commit suicide rather than become the brute’s victim. But Diana, having faith in the Sheik, fights gamely The Sheik and his horsemen assault the strong-hold’s walls. Once inside, the Sheik bests Omair in a hand-to-hand struggle. But at the moment of victory, a huge slave hits him a terrible blow on the head. For some day’s he lies at deaths door. Now the Frenchman tells Diana the true story of the Sheik. He is no Arab at all, but of English and Spanish descent. When a baby he was abandoned in the desert. An old sheik found him, reared him, had him educated in France, and eventually left him in command of the tribe. And so the story draws to a happy ending. The Sheik recovers and the two lovers set off for civilization and marriage. The public, especially the women, mobbed the theaters, and it was not very long before the psychologists were busying themselves with explanations. The simplest, I gathered, was that a surprisingly large number of American women wanted a mounted Sheik to carry them into the desert. Doubtless, for only a short stay, as in the case of Diana, after which they would be returned to civilization in style. Adult males were inclined to regard The Sheik with some levity. But the youths began to model themselves on Valentino, especially after he had appeared in Blood and Sand for us. In the latter picture, playing a Spanish bullfighter, he affected sideburns, sleek hair, and wide bottomed trousers. Soon thousands of boys and young men had cultivated sideburns, allowing their hair to grow long, plastered it down, and were wearing bell-bottomed pants. Lads in this getup were called “sheiks”. Thus two of Valentino’s roles were combined to get a modern sheik. As audience today viewing The Sheik laughs at the melodramatic story, the exaggerated gestures, and Valentino’s wild-eyed stares and heaving panting while demonstrating his affection for Diana. Yet some of the impact of his personality remains. He created an atmosphere of otherworldliness. And with reason, for there was much of it about him. Valentino born Rodolph Guguliemi in the village of Castellaneta in southern Italy of a French mother and an Italian father. When 18 he went to Paris and a year later migrated to New York City. It is known that he worked as a dishwasher, landscape gardener, paid dancing partner or gigolo. After a couple of years, he secured occasional vaudeville work as a partner of female dancers of more reputation than his own. Improvident by nature with expensive tastes, Valentino lived from day to day as best he could. All his life he was in debt, from $1. To $100,000, according to his status. Being fully convinced that a supernatural “Power” watched over him he did not worry. Mortal men found this power of Valentino’s hard to deal with. We raised his salary far above the terms of his contract. That seemingly only whetted the power’s appetite. It became downright unreasonable after Blood and Sand, with the lads of America imitating Valentino and women organizing worshipful cults. Evidently the power had mistakenly got the notion that we had agreed to make Blood and Sand in Spain any rate the idea crept into Valentino’s head. He became dissatisfied with his dressing quarters, wishing to be surrounded, apparently in the splendor of a powerful sheik of the dessert. Valentino rarely smiled on the screen and off, and I cannot recall ever having seen him laugh. It is true he could be charming when he wished. In dealing with a lady interviewer for example, he would give her a sort of look as if aware of something quite special in her, and treat her in an aloof but nevertheless cordial manner. On the other hand, he could be extremely temperamental. Harry Reichenbach, the public relations genius who had reversed Sam Goldwyn’s buzzer system, was now working for us. One day he called at Valentino’s dressing room to discuss publicity matters. “Does he know you”? a valet inquired. “Well”, Reichenbach replied “he used to borrow two or three dollars at a time from me and always knew to whom to bring it back”. The valet went away but soon returned with a word that his master was resting. It was my custom, as it had been in the old Twenty-sixth Street Studio, to go out on the sets every morning when in Hollywood. This provided an opportunity to get better acquainted with the players and technicians. Besides putting me closer to production, I hoped that such visits would make everybody feel that the business office was more than a place where we made contracts and counted money. The fact was that we kept as close tabs on the human element as on box-office receipts. Also, I was secretly envious of those who had an intimate hand in production, and, making myself inconspicuous, often watched activities. One day, I was privileged to see a Valentino exhibition such as I had been hearing about. He was arguing with an assistant director what about I did not know, and did not inquire. His face grew pale with fury, his eyes protruded in a wilder stare than any he had managed on the screen, and his whole body commenced to quiver. He was obviously in or near, a state of hysteria. I departed as quietly as I had come. The situation grew worse instead of better, and finally Valentino departed from the studios, making it plain that he had no intention of returning. We secured an injunction preventing him from appearing on the screen for anybody else. This did not bother him very much. He went on a lucrative dancing tour and was able to borrow all the money he needed. Valentino was married but the relationship had not lasted long, although it was still in technical force. Now he was in love with a beautiful girl named Winifred O’Shaughnessy. Her mother married Richard Hudnut, cosmetics manufacturer, and Winifred sometimes used his surname. She preferred, however, to be known as Natacha Rambova, a name of her own choosing. She was art director for Alla Nazimova, the celebrated Russian actress who was one of our stars. Like Valentino, Natacha believed herself to be guided by a supernatural power. They were married before Valentino’s divorce decree was final, and he was arrested in Los Angeles for bigamy. He got out of that by convincing authorities that the marriage was never consummated, and the ceremony was repeated as soon as legal obstacles were cleared away. Natacha Rambova appeared, as Valentino’s business agent wrote later, “cold, mysterious, oriental.” She affected Oriental garb and manners. Yet she had served Alla Nazimova competently, was familiar with picture making, and we felt she would be a good influence on Valentino. At any rate she brought him back to us. Now, as it turned out, we had two powers to deal with. She was the stronger personality of the two, or else her power secured domination over his. It was our custom to give stars a good deal of contractual leeway in their material. Natacha began to insert herself into the smallest details and he backed her in everything. His new pictures, Monsieur Beaucaire and The Sainted Devil, were less successful than those which had gone before. The Valentino cults continued to blossom, but his publicity was not always good. Newspapers poked fun at the sleek hair and powered faces of the “sheiks”. The situation was not helped when it became known that Valentino wore a slave bracelet. Many people believed it to be a publicity stunt. But the fact was that Natacha Rambova had given it to him. Any suggestion that he discard it sent him into a rage. A book he published, titled Day Dreams caused raised eyebrows. Both he and his Natacha believed in automatic writing and it seems that the real author was his power, or the combined powers, working through him. An item titled “Your Kiss” is a good sample.

Your kiss A flame Of Passions fire, The sensitive Seal Of love In the desire, The Fragrance of Your Caress; Alas At times I find Exquisite bitterness in Your kiss.

We did not care to renew Valentino’s contract, particularly since he and his wife wanted even more control over his pictures. He made arrangements with a new company, founded for the purpose, and work was begun on a film titled variously The Scarlet Power and The Hooded Falcon, dealing with the Moors in early Spain. Author of this story was Natacha Rambova. After the two had spent 80,000 traveling in Europe for background material and exotic props, the story was put aside. Another Cobra, was substituted with Natacha in full charge. It did poorly and the venture with the new company was at an end. Joseph Schenck was now handling the business affairs of United Artists, and he took a chance with Valentino being careful to draw the papers in a manner keeping decisions out of the hands of either Valentino or Natacha. Valentino accepted the terms, though reluctantly. Not long afterward the couple separated and Natacha sued for divorce. United Artists filmed The Son of the Sheik, which as it turned out, was the celebrated lover’s final picture. Valentino’s publicity became increasingly less favorable. He called his Hollywood home Falcon Lair, which opened him to some ridicule. The fun poked at the “sheiks” increased as the title of his new picture became known. He was in Chicago when the Chicago Tribune carried an editorial headed “The Pink Powder Puffs”. One of the editorial writers, it seems, had visited the men’s rest room of a popular dance emporium and there was a coin device containing face powder. Many of the young men carried their own powder puffs, and the could hold it under the machine and by inserting a coin get a sprinkle of powder. The editorial, taking this situation as its theme, viewed the younger male generation with alarm. Most of the blame was placed on “Rudy” the beautiful gardener’s boy, and sorrow was expressed that he had not been drowned long ago. IN an earlier editorial the Tribune made fun of his slave bracelet. Valentino’s “face paled, his eyes blazed, and his muscles stiffened” when he saw it according to the later account of his business manager. Seizing a pen, Valentino addressed an open letter “To the Man (?) Who Wrote the Editorial Headed “The Pink Powder Puffs” he handed it to a rival newspaper. “I call you a contemptible coward” Valentino had flung at the editorial writer, inviting him to come out from behind his anonymity for either a boxing or wrestling contest. After expressing hope that “I will have an opportunity to demonstrate to you that the wrist under the slave bracelet may snap a real fist into your sagging jaw,” he closed with “Utter Contempt”. That was in Aug 1925 Valentino came on to New York, and I was surprised to receive a telephone call from him inviting me to lunch. “It is only that I would like to see you” Valentino said “No business”. I would have agreed in any circumstance, but I was sure that he was telling the truth about not coming with a business proposition, since he was well set with United Artists. “Certainly, I answered where”? “The Colony” I had already guessed his choice since The Colony was probably New York’s most expensive restaurant. He liked the best. We set the time. Valentino and I had barely reached The Colony when it became apparent that every woman in the place having the slightest acquaintance with me felt an irresistible urge to rush to my table with greetings. Though overwhelmed, I remained in sufficient command of my senses to observe the amenities by introducing each to Valentino. He was 31 at this time, apparently in the best of physical condition, and, in this atmosphere at least was relaxed. I do not know whether his divorce decree was yet final, but Natacha Rambova was in Paris. Recently, Valentino’s name had been linked with that of Pola Negri one of our major stars. “I only wanted to tell you,” Valentino said after things had quieted down, “that I’m sorry about the trouble I made – my strike against the studio and all that. I was wrong and now I want to get it off my conscience by saying so”. I shrugged, “It’s water over the dam. In this business if we can’t disagree, sometimes violently, and then forget about it we’ll never get anywhere. You’re young. Many good years are ahead of you.” And so we dropped that line of talk. Valentino truly loved artistic things. He spoke of his ambition, when the time of his romantic roles was over, to direct pictures. I had the feeling that here was a young man to whom fame and of a rather odd sort had come too rapidly upon the heels of lean years, and he hadn’t known the best way to deal with it. “Telephone me any time”, I said as we parted, and we’ll do this again. I enjoyed myself”. And I had. A day or two later I picked up a newspaper with headlines that Valentino had been stricken with appendicitis. At first it was believed that he was in no danger. But he took a turn for the worse, Joseph Schenck and his wife Norma Talmadge came to our home to wait out the crisis. Schenck was bringing encouraging reports from the hospital, when suddenly there was a relapse. Valentino died half an hour past noon on August 23, 1925. It was a week to the minute since our meeting for lunch. I, for one, was stunned by the hysteria which followed Valentino’s death. In London, a female dancer committed suicide. In New York, a woman shot herself on a heap of Valentino’s photographs. A call came through to me from Hollywood “Pola Negri is overwrought, and she’s heading to New York for the funeral”. “Put a nurse, and a publicity man on the train,” I said, and “ask Pola to guard her statements to the press”. After Pola’s arrival, my wife and I called at her hotel to offer condolences. Though very much upset, she intended to remain in seclusion as much as possible. Valentino’s body was laid in state at Campbell’s Funeral Home at Broadway and 66th Street, with the announcement that the public would be allowed to view it. Immediately, a crowd of 36,000 mostly women gathered. Rioting described as the worst in the city’s history began as police tried to form orderly lines. Windows were smashed. A dozen mounted policemen charged into the crowd time and time again. After one retreat of the crowd, 28 women’s shows were gathered up. Women then rubbed soap on the pavement to make the horses slip. The funeral home was now barred to the public. Those who got in had nearly wrecked the place by snatching souvenirs but next day another crowd gathered when news spread Pola Negri was coming to mourn. She was spirited in through a side door. Word came out that she had collapsed at the bier, which she had and for some reason it excited the crowd. On the day of the funeral 100,000 persons, again mainly women lined the street in the neighborhood of the church in which it was being held. I was an honorary pallbearer, along with Marcus Loew, Joseph Schenck, Douglas Fairbanks, and others from the industry. Natacha Rambova was not present, being still abroad. But Valentino’s first wife Jean Acker, collapsed, and Pola Negri heavily veiled, was for many moments on the point of swooning once more. As the funeral procession left the church, the throngs fell silent except for subdued weeping of many of the women. The body was sent to Los Angeles for burial. The Valentino Cult, I am told, is still in existence. At any rate, enough women visit his grave every year to have provided the grave keeper with enough material for a book about them.

Resource

Adolph Zukor (1953). The Public is Never Wrong, Chapter 17, Putnam Publishers, New York.

You must be logged in to post a comment.