The other day, I saw in the theater section of my favorite newspaper a headline “THE SHEIK RIDES AGAIN” over a story about the recent revival of interest in the late Rudolph Valentino. The story reminded me of my embarrassing embroilment in the riots which followed the movie idol’s sudden death in 1926. In fact, I was arrested at Valentino’s wake, after a brisk morning battle with the NY Mounted Police. Finally collared and jailed, I was dragged into court to face charges of 1 knew not what misdemeanors and felonies. It is a true story; yet it occurs to me that its details may seem to verge on the implausible. The death of the handsome young movie star was surely a sad event. And his wake—when his body lay in state in Campbell’s Funeral Home, so that his admirers might file by and pay their last respects to their hero—should have been a solemn occasion. Why then the riots and the clanging ambulances and the mounted police charging in at the gallop? Why should I, a reasonably respectable and peaceable young man, with no special interest in the late sheik of the silent screen, have become so entangled in his obsequies? And why should the mourners have ceased their keening to cheer my defiance of law and order? Obviously, if I am to emerge from this recital with my reputation to veracity intact, some explanation is in order. Note that my mishaps occurred during what Westbrook Pegler has termed the Era of Wonderful Nonsense. In the mid-‘2O’s Coolidge Prosperity was well under way. Another world war was inconceivable; serious depressions, according to eminent authorities, were a thing of the past. The public, having no major crises to worry about, concentrated its attention on what Frederick Lewis Allen called “a series of tremendous trifles” Millions worked up a head of emotional steam about whether Floyd Collins would escape from the cave where he was trapped, whether Gertrude Ederle would swim the English Channel, whether there would be acquittal or conviction in the gaudy Hall-Mills murder case. It was a time of contagious mass excitements. Crowds flocked to the Scopes trial in Tennessee to hear William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow debate whether men were descended from monkeys. Others thronged to watch couples in a dance marathon totter toward exhaustion, or to see how long Shipwreck Kelly could perch atop his flagpole. Among these excitements, and longer lasting than most, was the Valentino craze. The nation’s more susceptible womenfolk, from flappers to grandmothers, were under the spell of the young Italian-American star who had brought a new torridity to cinematic amour. The mania began with the first showing of a silent film called The Sheik in 1921. Valentino played the lead: a romantic Arab chieftain, passionate, masterful, and irresistible. He snatched Agnes Ayres from her steed. “Stop struggling you little fool,” flashed the subtitle. Hot stuff. Overnight he became a star. Millions of women began to idolize him. The adoration increased with each succeeding film of the great lover. With the appearance of The Son of The Sheik in the summer of 1926, the Valentino worship became feverish. On the morning of August sixteenth came the shocking news, on the front page of even the staid New York Times, that the handsome thirty-one-year-old silent film star had been rushed to a hospital in New York for critical surgery—appendix and ulcers. In the next few days the bulletins were reassuring. Then, front page again: PERITONITIS FEARED, CONDITION ALARMING. On Monday, August twenty-third. huge headlines: VALENTINO DEAD THOUSANDS OUTSIDE HOSPITAL WEEP AND PRAY. The stories from Hollywood said that Pola Negri who recently had announced her engagement to Valentino, was prostrated by grief, with two physicians trying to control her hysteria. Valentino’s management said the body would lie in state for several days so that mourners could have another look at their hero. This announcement set off a saturnalia of sentimentality that lasted for two weeks, quieting down only after poor Valentino was at last laid to rest in an elaborate Hollywood Mausoleum. Many of the strange, typical celebrities of the day got into the act with lavish manifestations of grief. Among them were Mrs. Frances (Peaches) Browning, whose marital adventures with “Daddy” Browning had provided a field day for the artists of the Daily Graphic. Also, Mrs. Richard R. Whittemore, still in mourning for her husband, the bandit hanged for murder after a sensational trial. Strangest of all was a small, earnest looking man who introducing himself as Dr. Sterling Wyman, Miss Ncgri’s New York physician, bustled into the headlines as impresario of the complex funeral arrangements. He was gracious and accessible to the press. He discoursed learnedly on the details of Valentino’s fatal illness. The authoritative identified him as “the author of Wyman on Medico-Legal Jurisprudence.” A few days later he was exposed as a notorious impostor and fraud, with a long record of arrests and convictions, and fancy aliases such as Ethan Allen Weinberg and Royal St. Cyr. His proudest coup had been engineered in 1921 when, posing as an officer of the U.S. Navy, he had escorted the Princess Fatima of Afghanistan to Washington and introduced her to President Harding. (He drew eighteen months for that one.) 1 have sketched in this unlikely but authentic background of events with the hope that today’s readers, thus inured to the improbable doings of the 192O’s, will give credence to my own peculiar part in the proceedings. In that summer of 1926 I had paid only casual attention to the Valentino headlines. I was not one of his fans. Besides, I was preoccupied with my own concerns, which had reached a turning point. For nearly four years I had been practicing corporation law in Wall Street, with a pleasantly rising income but growing dissatisfaction. I suffered from a yearning to write, and the drafting of 200-page corporate mortgages was not my idea of vibrant prose. Early that spring I had met Grace Cutler. With a rare flash of good sense I fell in love with her immediately and permanently. She was a young newspaper reporter, doing modestly paid night assignments for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The only way I could pursue my courting was to accompany Grace on her assignments. This was a new and fascinating world to me. Why couldn’t I, too, be a reporter? Grace approved of the idea. After we were married on May twenty first, I became more cautious. Now I had a husband’s responsibilities. A cub reporter in those days got only twenty or twenty-five dollars a week to start. Had I not better delay my plunge into journalism until we had saved up SIO.OOO or so from my legal earnings? My bride was brave and wiser than I. She argued that if I really wanted to make the change, the sooner the better. We were young and could stand a spell of living on a shoestring. Each year, we put it off the decision would be harder, with new excuses for prudent delay. By the end of July she had so bucked up my courage that I applied for a job with the New York Herald Tribune. The city editor, after warning me of my folly agreed to give me a try as a reporter at twenty-four dollars a week, beginning at the end of August. Thus, when the news of Valentino’s death hit the headlines on Monday, August 23. 1926, I was serving my last week with the law firm of Chadbourne, Hunt, Jackson and Brown. It was still my custom to accompany Grace on her evening assignments, not only for pleasure but to learn something more of my new trade. On that Tuesday evening, Grace and I met for dinner in a small Italian restaurant in Greenwich Village. We had scaloppini, washed down with what was called “red ink.” This was supposed to be a wine of the Chianti family, but the kinship was not close. Cheered by the wine, I looked forward to an entertaining and instructive evening. “Well, Grace,” I said, “what’s the journalism lesson for tonight?” “I’m afraid it’s pretty gruesome,” she said. They’ve got poor Valentino laid out for public view in the Gold Room at Campbell’s Funeral Home—Broadway and 66th. They’ve rigged him up in full evening dress in a fancy silver casket. My city editor says the fans are putting on a regular mob scene outside, scuffling to get in. The pressure of the crowd pushed in one of Campbell’s big plate-glass windows. Three cops, a photographer and some of the women were cut so badly by the glass that they had to be taken to the hospital. It sounds kind of ghastly—I don’t want to drag you into this.” It also sounded kind of dangerous, I said. A girl could get hurt in a mob like that. This was the very time she needed a man’s strength and judgment. “I will protect you,” I said. On our way to the subway 1 remembered that the Aliens and the Fowlers were coming to our apartment for dinner the next evening. “They like rum swizzles. I reminded Grace. “Let’s drop by Henry’s joint and buy a couple of pints of his fine, five-day-old Bleecker Street rum.” We did, and I tucked a pint bottle of the potent stuff into each of my hip pockets. While we walked on toward the subway it began to rain, and I was glad I had brought my umbrella. We took the Inter-borough Line to Broadway and 72nd Street. As we came up from the subway, we saw a dense column of people, mostly women, shuffling southward along the cast side of Broadway toward the funeral parlor six blocks away. Police kept them in line. From the other side of the street an even larger crowd, straining against (he police lines, was struggling to dash across and break into the column which was approaching the Mecca of mourning. Every now and then a group of frantic women would elude the foot patrolmen and make a wild rush, only to be turned back by mounted police. With Grace holding aloft her reporter’s police card as a passport, we made our way southward down the cleared space. The rain had stopped, but the paving gleamed wet under the arc lights. It was 8:30 P.M. As we neared Campbell’s, the thwarted crowds on the west side of Broadway grew more turbulent. The cops were having a hard time. Here and there the street was littered with women’s shoes, trampled hats, and bits of torn clothing— evidence of forays which had failed. Now a veteran sergeant of foot police intercepted us. “Where you think you’re going?” he demanded. Grace showed him her reporter’s card. He softened. “The Brooklyn Eagle, huh? I was born and raised in Flatbush. Whole family used to read the Eagle. What can I do for you?” “The editors want me to go into the Gold Room where the casket is,” Grace said apologetically. “You know—get the atmosphere.” “It’s awful in there, miss,” said the sergeant gloomily. “Women screeching and fainting. No place for a nice young lady like you. But—well, seeing you’re from the Eagle, I guess I can slip you in. How about this guy—er—this gent’man with you. He a reporter?” “Not yet.” Grace said. “He’s my husband.” Then he can’t go in—sorry—not unless he goes back about ten blocks and stands in line three or four hours. Then you might not find him again all night, not in this mob. Tell you what, mister,” he said, turning to me. “You stand on the northeast corner over there, in that space we’ve cleared by the lamppost. You got my permission. Stay right there until your wife gets back.” 1 took my place as directed, and the sergeant escorted Grace toward the maelstrom around the entrance. That was the last I saw of the kindly sergeant. Alone on the corner 1 was in an exposed position, a sort of no-man’s land. On one side, ten feet away, trudged the south-bound column, silent now except for a subdued moaning as it approached its grim goal. Across the street the mob was bigger and noisier than ever. The weeping and wailing were mingled with shrill imprecations directed at the mounted cops. Hysterical women, foiled in every rush by the hard-working horsemen, regarded them as personal enemies. “Cowards!” they screamed. “Cossacks!” For ten minutes or so 1 stood on my corner, leaning on my umbrella and trying to look inconspicuous. Then the mounted patrolman guarding my sector, cantering back after helping repel another feminine charge a half block to the south, spotted me. He reined in his horse and glared. “Hey, you!” he shouted. “How’d you sneak over there? Get back across the street.” “I’m waiting here for my wife,” I yelled back, standing firm. The ridiculous excuse seemed to exasperate him. He touched the flank of his horse and rode straight at me. I dodged instinctively and dashed out into the street. The cop wheeled his horse and followed. I flourished my umbrella, feinted to the left, dodged to the right, and made an end run back to my corner. The cop rode at me again. “I got permission to stand here!” I yelled. “From the sergeant.” I’m not sure he heard me above the tumult. If he did, he paid no heed. Again I dodged, ran, feinted, ducked. As a former track man I was still fast on my feet, and the horse was more handicapped than I by the wet, slippery asphalt. As 1 once more sprinted safely back to my post, I heard a louder roar from the crowd. They were cheering me. There were cries of “‘Ray! . . . Attaboy! . . . That’s showing ’em. Mister!” They were all for me; I was the first person successfully to defy the hated “Cossacks.” There is something stimulating in the cheers of the multitude, however irrational. I caught my second wind and went on with the game. My triumph did not last long. As I dodged and weaved, 1 heard the ominous clop-clop of hoofs converging from north and south—reinforcements coming up. For perhaps another ten seconds 1 managed to out maneuver them all. Then just as I darted back to my corner, I felt the tap of a night stick across my brow. It didn’t hurt me, but it splintered the right lens of my horn-rimmed glasses and threw me off stride. A hand reached down and grabbed my coat collar, tearing the fabric halfway down the back. My original pursuer, whom I shall call Patrolman John Jackson of Troop B, vaulted down from his saddle and handed the reins of his foam-lathered charger to one of the fellow troopers who had helped in the roundup. He seized my arm. “You’re under arrest,” he growled. As he led me away, the crowd booed. At this moment Grace reappeared, justifiably concerned. “Oh, dear, are you hurt?” she cried. “Not a bit,” I reassured her. “Just rumpled. I feel fine.” Actually 1 did not feel fine at all. With the excitement of the chase over, I realized 1 was in a bad spot. 1 remembered now those two infernal pints of rum in my hip pockets. They would be discovered when I was frisked at the West 68th Street Police station. “Possession and transportation of intoxicating liquors ” The New York police were usually lenient toward liquor violations, but I had heard that if they were angry enough they would sometimes throw the book at a defendant. And the hand gripping my arm was trembling with rage. Fortunately the paddy wagon had not been summoned. Maybe on the walk to the station house I could talk my way out or out—or part way out—of the hole I was in. I began by politely asking the officer his name, which I jotted down. Then I handed him my legal card, showing me as an associate of the imposing firm of Chadbourne, Hunt, Jackson and Brown. Covertly mopping my brow, I began: “Mr. Jackson,” I said gravely, “I’m afraid you’ve got yourself in real trouble” “Trouble!” he snorted. “How about you? Disorderly conduct, resisting arrest, fugitive from justice, dangerous weapon—the spike of your umbrella might have put my horse’s eye out.” “Nobody hurt your horse,” I retorted. “I’m the one who’s been injured. I am a member of the bar in good standing. I was present on proper business, escorting my wife, who is an accredited newspaper reporter. A sergeant, your superior officer, gave me specific permission to stand on that corner until my wife returned. I told you that, but you tried to ride me down. Then you and your mounted pals took out after me, cornered me, tore my coat, clubbed me, and smashed my glasses. It’s a blessing I still have my eyesight. All this—and the terrible humiliation of public arrest—before thousands of people.” “I never heard you about the sergeant,” Jackson said in a low voice. “So you say now. You know what false arrest means? It means the arrest, without proper inquiry, of a citizen who you for damages and probably the Police Department besides. This was false arrest with bells on, and the damages, from what I know of juries, will be heavy.” As I held forth further in this vein I almost convinced myself that the arrest had been a travesty of justice, a blot on the proud escutcheon of New York’s Finest. Orating thus. I felt Jackson’s grip slackening. I looked at him as he strode beside me, his eyes fixed on the ground. He was a sandy-haired, well-built, nice looking man. But now he seemed dead tired, bewildered, and uneasy. He was sweating. I felt a twinge of sympathy. Maybe I was carrying my bombast too far. Grace, trotting along beside us, had also, noticed Jackson’s dejection. Speaking purely out of kindness, she struck what turned out to be the right note. “Now. Beverly,” she said, “Officer Jackson was only trying to do his duty. With all that mob of women screeching at him, anybody could make a mistake.” “That’s right, ma’am,” said Jackson eagerly. “It was enough to drive a man nuts. I was bucking those crazy women from nine o’clock this morning—twelve hours without a letup. It was the worst day I ever had on the force. Those women were clear out of their heads. All ages, schoolgirls to real old tough biddies about seventy,” “I saw some men there too,” said Grace, defending her sex. “All the less excuse for them,” said Jackson, “unless maybe their wives drug ’em there.” “That’s why my husband was there,” Grace said. “I got him into this. He came along to protect me.” “Protect you, huh?” Jackson started to grin. Then his face clouded as he remembered the serious situation. “Oh, my! If I’d only of known. Why did I have to stick my fool nose into this?” Sensing the friendlier atmosphere, I hastened to help it along. “Listen. Mr. Jackson,” I said. “I was just hot under the collar when I talked about suing you. I wouldn’t do that. You were doing the best you could under tough conditions. Forget it.” “You really mean that, Mr. Smith” Jackson asked. “That’s what 1 call decent. I didn’t mean any harm. You didn’t mean any harm.” He paused for a minute in thought. “Honest, I’d tum you lose now if I could. I turned in my horse. If I show up empty-handed at the station, there will be hell to pay. I got to take you in. But I’ll go easy on you, and you go easy on me, and we’ll both come through O.K. Don’t you and the Missus worry.” All three of us had been more tense than we realized. Now, with surging relief, we became as chummy as old friends. I complimented Jackson on his horsemanship. He told Grace her husband was the slipperiest eel he ever tried to catch, then improved the doubtful compliment by saying 1 was “a regular Red Grange for broken-field running.” “Red Grange with an umbrella,” Grace said. She and Jackson laughed. I didn’t join in because just then the green lamps of the police station came into sight. The incriminating pints grew heavy in my pockets. Time was running out. I decided to entrust my Fate to our new Friend. “Mr. Jackson,” I said. “I’ve got a little problem. We’re expecting guests, so I stopped off in the Village and bought a couple of little pints of rum to take home, I’ve got them in my hip pockets now. When they search me Patrolman Jackson stopped, frowned and pondered. “Well, now,” he said judicially, “1 don’t see anything so bad in taking a little alcoholic beverage home. For consumption strictly on the premises of your own domicile. Personally, that is. But some bluenose sour-puss—we got a Few of that kind on the Force—is liable to get technical on you. That could be bad. Tell you what. Right now—I’m not looking, see—if you was to slip those two pints to the little lady here, she can put them in that big handbag of hers no sooner said than done. At the police station I was booked and put through the routine. Patrolman Jackson hemmed and hawed and said he guessed there had been some disorderly conduct, but it was kind of complicated and maybe there was some sort of misunderstanding and the desk officer cut him short. “Never mind that now, Jackson,” he said. “Captain Hammill called up about this case ten minutes ago, from the scene of the disturbance. Says you should take your prisoner down to Night Court.” Uneasy again, Jackson, Grace and I caught a taxi to Night Court on West 54th Street. Grace waited in the courtroom for my case to be called. I was turned over to attendants who locked me in a room among a lot of other prisoners. They were the dregs of the city’s night life: pickpockets, panhandlers, canned heat derelicts, petty thieves. In this depressing atmosphere my apprehensions returned. Were Jackson’s superiors preparing to make a Fuss about the case? Would they sway Jackson’s had said, adding that he had had a trying day, and that the screaming of the mourners had evidently kept him from hearing my shouts about “permission.” “How did your coat get torn, sir?” asked the magistrate. (I was cheered by the “sir.”) “Just an incident of the general rioting. You’re Honor,” I said. He thought for a moment, evidently puzzled but amused. “An unusual case,” he said. “I don’t quite see how it reached this court. Apparently there was an honest misunderstanding. Charges dismissed, with no reflection on Mr. Smith or Patrolman Jackson.” Jackson, Grace and 1 left the courtroom and strolled down 54th Street, walking on air. “Some day!” exclaimed Jackson. “Now I better get home to the Family, but first, Mr. Smith, you got to let me pay for the broken glasses and the tailor repairs for your coat.” Grace and I joined in assuring him this was impossible; we would just charge it off to experience. On this cordial note, and with warm handshakes all around, we parted. Grace and I took the subway to Brooklyn and went into the Eagle; she still had her story to write. After a general lead about the riotous wake, she concocted an ingenious story. It told of a henpecked young husband—anonymous—who had been dragged into the rumpus by his foolish wife, a rabid Valentino Fan. Determined to see the body, she parked her spouse on a corner and fought her way into Campbell’s. On her return she found her husband being led away by the police. And so forth. Grace wrote the story discreetly. There was no mention of the Demon Rum, and there was a special tribute to the skill and patience of the mounted officer who had Jackson, Grace and 1 left the courtroom and strolled down 54th Street, walking on air. “Some day!” exclaimed Jackson. “Now I better get home to the family, but first, Mr. Smith, you got to let me pay for the broken glasses and the tailor repairs for your coat.” Grace and I joined in assuring him this was impossible; we would just charge it off to experience. On this cordial note, and with warm handshakes all around, we parted. Grace and I took the subway to Brooklyn and went into the Eagle; she still had her story to write. After a general lead about the riotous wake, she concocted an ingenious story. It told of a henpecked young husband—anonymous— who had been dragged into the rumpus by his Foolish wife, a rabid Valentino Fan. Determined to see the body, she parked her spouse on a corner and Fought her way into Campbell’s. On her return she found her husband being led away by the police. And so forth. Grace wrote the story discreetly. There was no mention of the Demon Rum, and there was a special tribute to the skill and patience of the mounted officer who had made the arrest. Evidently the editors Found it amusing: they gave it a big two column play under a fine photograph of the police struggling with the mob. The next day Grace got a call from thc city editor of the New York Daily News. He had been delighted with her story (which was exclusive) and offered her a job at twice her pay on the Eagle. She took it. And so we lived happily ever after.

Monthly Archives: Aug 2015

14 Sep 1926 – Eagle’s Newsbeat Reporter Explained to Radio Fans By Reporter

An account of how “The Brooklyn Eagle” scored a beat on all the other metropolitan papers was the subject of the weekly current events talk last night by Marjorie Dorman over Radio Station WOR. Miss Dorman took her radio audience behind the scenes of a modern newsroom as she explained in detail how she had ferreted the story in detail of Dr. Sterling Wyman, the most chivalrous of imposters. Miss Dorman had personally covered all the details of the funeral of Rudolph Valentino. The story which came to her attention stated that Dr. Sterling C. Wyman, Brooklyn declared that Pola Negri was never affianced to Valentino. Her suspicions were aroused because out of all the details familiar to her when she covered the Valentino Funeral she could recall a Brooklyn Physician by that name or called in to give evidence. She told how from there on the whole story of the grandiose fraud by “Wyman of Many Aliases” was exposed

23 Aug 2015- 88th Annual Valentino Memorial Service Review

23 Aug 15, Hollywood Forever Cemetery, was the location for the annual memorial service that I attended for a second year. What a difference from last year to this year, I felt it was a meeting of old friends and with Mr. Tracy Terhune’s genius in putting together another memorable tribute.

This years tribute was the 90th anniversary of Rudolph Valentinos movie “The Eagle”. The montage and the clips from the movie were very moving. The featured singers the talented “The Wegter Family” were once again a true delight to listen to. Mr. Ellenberger spoke of Historical Valentino Sites was very interesting. However, hearing Mr. Zachary Kadin talk about the story behind the Valentino Eagle Coin was new and insightful.

I wanted to take a moment to give a personal thank you to Mr. Tracy Terhune for his continued kindness, Mr Christopher Riordan for being gracious to a fan of his, to Ms. Sylvia Valentino-Huber for taking time for a photo with me and especially to everyone else I had the pleasure of meeting for the first time. I will see you all again next year at the 89th.

2015 Valentino Memorial Service

It’s time for the 88th Annual memorial service… I’m here attending for the second year and I am quite excited to attend…

30 Aug 1926 – Valentino Commentary

It was with boiling indignation that I read the letter of “Disgusted”. It was full of disrespect to the late Rudolph Valentino, yet your correspondent stated, “Far be it from me to say anything disrespectful of one who has passed through the great divide.” We women know what was at the bottom of the letter – pure jealousy. then he states that the flapper must save some excitement. Let me tell him that if his life has been as clean as was that of Valentino then he has something to be proud of.

Marie Crossett, Adelaide.

18 Oct 1926 – Weinberg Imposter Sued on Forgery Charge

Posed as a personal friend at Valentino funeral is now mixed up in a civil suit involving a charge of forgery. Weinberg could not be located this morning. His wife answered the telephone, stated that she did not know where he was, and that he had told her nothing about his latest escapade. Weinberg, who passes as “Dr. Sterling C. Wyman” and lives at 556 Crown Street, Brooklyn, was served with a restraining order as he entered his home Thursday night. The papers restrain him from assigning to anyone a $10,000 mortgage on the beautiful $50,000 home of Mrs. Pierre Roos at New Rochelle. Mrs. Roos through her attorneys, Butchers, Tanner & Foster, asserts that she never signed Weinberg’s mortgage. She signed an application for a mortgage, according to her attorneys. But an actual mortgage bearing her signature was recorded at 9:00 a.m. on 23 July. Last at the Westchester County Clerk’s office, according to the attorneys. Two hours later a mortgage of $20,000 on the same property was recorded by Butcher, Tanner & Foster with the same clerk. The restraining order that was served on Weinberg on Thursday was granted by Justice Morschauser of the Worchester Supreme Court on Wednesday last. The injunction hearing is scheduled for 22 Oct in the Westchester Supreme Court.

2015 Valentino Still Appreciated

This year as the anniversary of the death of Rudolph Valentino approaches I am reminded that he is still adored by fans the world over. In these modern times, there is a true appreciation of his acting as an art form. During his lifetime Rudy dealt with many battles to show the world that he took his profession seriously. In 1923, he said “feeling and not acting is what lifts a love scene from commonplace to the realms of realism and romance”.

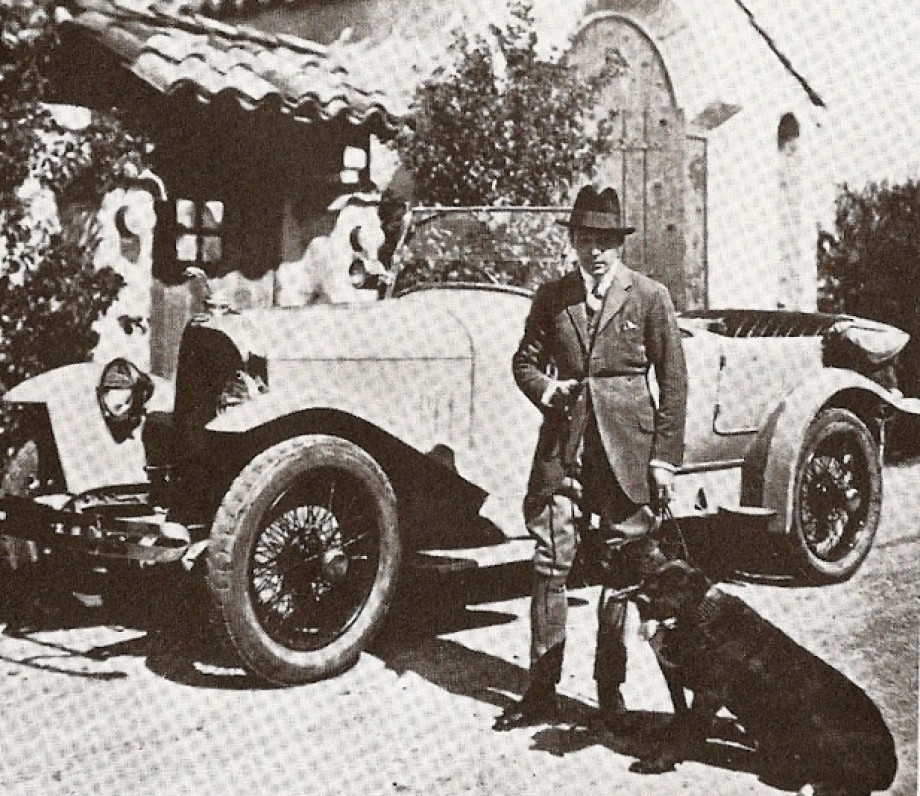

5 Sep 1926 – Dupe Shows Up Again – Acts as Manager for S. George Ullman, Former Manager of the Late Rudolph Valentino

Ethan Allen Weinberg, ex-convict and leading quick change artist has now added S. George Ullman, business representative of the late Rudolph Valentino to his long list of dupes. Mr Ullman believing Weinberg’s statement that he is both an M.D. and a member of the NY Bar, has permitted Weinberg to represent him at the offices of the Manhattan District Attorney where this Baron Munchausen of Brooklyn spent an hour yesterday discussing the demands of the anti-Fascist element for an autopsy on Valentino’s body. As one of Weinberg’s dupes Ullman is in excellent company. When not hob-knobbing with the representatives of the District Attorney’s Office the last few days, Weinberg has been issuing statements to the press explaining that he has been in charge of Pola Negri’s hysterics and denying that she and Rudy were affianced. A letter bearing the imprint of S. George Ullman and signed with his name in ink, reached the newspaper offices yesterday. Mr. Ullman thanked the press for its co-operation and asked that the diagnosis of Valentino’s preoperative condition made by Dr. Harold D. Meeker, be given publicity. This was made to offset the cause of death had been foul play of some sort. The letter was dated 23 Aug and apparently dictated by Ullman before he left for Hollywood. At the bottom of the letter was written, above Mr. Ullman’s initials: “This report was concurred in by three reputable surgeons who were consulted this a.m. together with the legal aspects by Sterling C. Wyman, medico-legal expert who was a dear friend of Valentino”. The last straw to break the camel’s back of “Dr.” Wyman’s identity was furnished by the man himself. His suspicion aroused by questions the writer had addressed to him over the telephone early yesterday, Wyman-Weinberg called up the office of “The Eagle” sometime later to assure the City Editor that really everything was quite as it should be. Of course, he said, he was a doctor, he was a lawyer also, and he combined the two professions by engaging in the legal or judicial aspects of medicine. But he certainly was a doctor, with a degree. Why, he was on staff of the Flower Hospital, Manhattan, from which he was telephoning at that very moment. No, he added, he would not remain at the hospital very long. He was going out of town would leave in a few minutes. Whereupon the hospital officials were questioned about him. Over the telephone, a minor clerk said, yes, there was a Dr. Wyman on the hospital staff, and only a few minutes ago he had left word he was going out of town and would not be back until Wednesday. But a personal inquiry at the hospital on E. 64th Street considerably modified this first bit of information. Hospital officials looked up their records and found no Wyman or Weinberg on their list of doctors. “He comes here frequently to visit with one of our interns” she explained. “Everybody knows him as Dr. Wyman and I suppose that’s why whoever answered the telephone was under the impression that he was on our staff. But he’s not on the staff. “Would you”, she was asked, “recognize him from a picture”? She thought she could and a photograph of Stephen Weinberg as he looked when convicted in the Brooklyn Federal Court for impersonating a Naval Officer was shown her. “That’s he”, she said. That’s Dr. Wyman. At 556 Crown Street, a 32 family apartment house a block from the Carson C. Peck Memorial Hospital, “Wyman” has been a man of mystery for the past two and a half years. He is known as Sterling Clifford Wyman to tenants of the house, but there are many residents of the section who recall him as the Ethan Allen Weinberg, whose gigantic hoaxes have kept him before the public ever since his peculiar abilities manifested themselves years ago. The man who has been so many times in the toils of the law is even buffaloing the Police Department at present. Posing as a physician and getting the necessary letters of introduction, he boasts a police card which permits him to sail past traffic signals in his three motor cars, when the coveted P.D. sign is attached. According to neighbors in the house ‘Wyman” advertised last autumn for a chauffeur, and engaged one only after he had kept 40 applicants for the job waiting all day in the lobby and on the sidewalk. “He went to the Valentino funeral looking like a million dollars” said one neighbor. “He hired a Rolls Royce for the occasion and was gotten up in the most expensive funeral attire he could secure”. This was done to impress Joseph Schenck, Ullman, Norma Talmadge, Douglas Fairbanks, Richard Dix, and all the other celebrities who gathered at the Actors Chapel St Malachy for the funeral services of Weinberg’s “dear friend” Valentino. The fact that Brooklyn’s indefatigable Baron Munchausen has popped up again in the self-styled role of dear friend of Valentino in the not to be wondered at. According to physicians, who have examined Weinberg on the many occasions of his clashes with the police, has “ideas of a grandiose nature” whenever a celebrity bobs into the limelight also. When the venerable Austrian surgeon Dr. Lorenz, came to NY Weinberg called on him, represented himself as Dr. Clifford Wyman, and said he called as the personal representative of Health Commissioner Copeland and wanted to co-operate at the clinics. Lorenz offered him a salary as his secretary. Acting as go-between in the clinic waiting room. It was an easy matter to extract a $5 dollar bill from a mother eager to get place and preferment for her crippled child. Copeland exposed the imposter and “Wyman” dropped out of sight. Calling at the Waldorf with his accustomed savoir faire, he presented himself as Lt. Com. Ethan Allen Weinberg to the Princess Fatima of Afghanistan. The lady with the emerald coquettishly set in her nose was delighted with the persuasive man in naval uniform. He offered her what appeared a perfectly good letter of introduction and said he could get her an audience with President Harding. If her credentials were satisfactory. In a flutter the lady offered them, as well as an expense account, to the ingratiating officer of gallant address. He actually introduced her to the President at a private three minute audience. As Weinberg was leaving the White House, however, he was nabbed by Secret Service Agents impersonating ordinary individuals may not be a jail offense if no fraud, larceny or forgery results, but impersonating an officer is a very different matter. Weinberg got 15 months in Atlanta Penitentiary and was released Feb 1924. One of is most amusing pranks with the press was when the Harold McCormickes returned from Europe a few weeks before they were divorced in Chicago. Weinberg got a pass for the revenue cutter which went down the bay, telling the ship news men he was attached to the McCormick retinue. This time he again used the first name of Sterling, dropped the last name of Weinberg and was Capt Sterling Wyman he was using with George Ullman. He told the ships newsmen he could officially deny the rumored McCormick divorce and was sure it would never take place. He told the McCormick’s he was a reporter. At the Manhattan Hotel where Harold McCormick stayed for 24 hours the Brooklyn fraud managed to stay for 24 hours before McCormick booted him out. Representatives of the Kings County Medical Society, reading in Manhattan newspapers of a “Dr. Sterling C. Wyman, of 553 Crown Street, who had been in constant attendance” on Pola Negri declared yesterday there is no physician by that name. In the telephone book Wyman fails to use his alleged medical title. Weinberg in duping his victims uses a long list of aliases. When he was sentenced in an Atlanta Prison for 18 months in 1922 for impersonating a naval officer he was charged by the Federal judge in Washington D.C. as Stephen Weinberg, alias Stephen Wyman, alias Ethan Allen Wyman, alias Clifford G. Wyman, alias Sterling Wyman. It was as Dr. Sterling C. Wyman, that he duped Ullman. It was as Capt. Sterling Wyman that he once rode for 24 hours in the rolls royce of Harold McCormick. Posing alternately as lawyer, physician, or officer of the Navy or Army this chameleon of Brooklyn has now gotten into the limelight again. His methods never vary. He is always interviewed by the press and enjoys for a time all the éclat of the limelight which his victims enjoy. Then he is discovered, he disappears and bobs up six months later under a change of alias, smiling and debonair, suave in a way really likeable. His nerve is truly great. “He has ideas of a grandiose nature” said the physician. This accounts for the fact that Weinberg never tricks anyone except a celebrity, swaggers up to reporters and gives out interviews which are sure to reveal his identity to anyone familiar with his case and maintains placidity when he is thrown out, only to bob up later in the society of some other notable. He remained in Dannemora from Oct 1917 to April 1919, having been sent there from Blackwell’s Island, to which he was committed on the charge of forging the name of Senator William Calder to a bank recommendation. Asked yesterday, if he were any connection of the man of the many aliases, Dr Sterling Wyman indignantly replied he was a Brooklyn M.D. in good standing and the author of “Wyman on Medical Jurisprudence”. At Kings County Medical Society, however, he stated that he certainly is nothing of the sort and that his name fails to appear in the directory of the American Medical Association as a doctor in good standing anywhere in the United States. Weinberg appears happy only when he is near the great. He forges and impersonates apparently for this reason only. He is in his own way a genius. He got himself before the Republican National Convention with a letter expressing the hope that his “efforts would meet with unrivaled victory” and he got a letter from Senator Pat Harrison which carried him before the Democratic National Committee. He knows nothing whatever about medicine. But he once convinced the Foundation Underpinning Co. that he did, and on his forged credentials that sent him to Peru where for three months he practiced medicine on the employees of the company before his deception was discovered. Weinberg was born in Brooklyn in 1893, the eldest of six children. He graduated from P.S. 18 and from Eastern District High School, from which he was graduated with honors in 1903. Somewhere he has acquired the Phi Beta Kappa Key sign of the honor of the fraternity to which only a few brilliant scholars are eligible. In November, of the same year Francis Cushman whose term expired in May 1903, appointed the young man as his personal page in the House of Representatives. Returning to Brooklyn, Weinberg blossomed forth as an orator in the cause of woman suffrage. He was made secretary of the Brooklyn Organization and was the only male delegate to the National Council of the American Woman Suffrage Association in 1909. At this time, he resided at 71-a Maurer Street and his mother was proud of him. The following year he was appointed Consular Agent to Port de Aubres, in Northern Africa, by the U.S. Minister to Morocco, who became acquainted with Weinberg when he was a page in the House. But Weinberg never got to Morocco, instead, at eh earnest request of his father, he was sent to Bellevue Hospital for observation. Employed as a demonstrator for airships in a Manhattan Department Store, living in a comfortable home, he had for some inexplicable reason taken a camera and flash powder from the store. From this time on Weinberg never again ran straight. In 1913, he was arrested for posing as “Lt Com Ethan Allen Weinberg, King’s Guard Consul General for Romania. In this capacity he tendered a dinner at the Hotel Astor to Dr. Alfonso Quinores, Vice President of San Salvador, and was arrested the next day for violating his parole from Elmira Reformatory, to which the man of many parts had been sent at earnest behest of his distracted parents. His next offense was the forging of former Senator Caider’s name. No man living has gotten away with the grand gesture more often than Weinberg, who in his way, is an artist. Impossible to cross his vivid trail again and again and no take off one’s hat to the man’s persistent nerve, audacity and aplomb. It is doubtful if there is anyone who under certain circumstances would not “fall” for the persuasive address of the man who in his own novel way is one of the famous personages of this borough.

New Yorks Greatest Imposter

Stephen Jacob Weinberg, otherwise known as S. Clifford Weinberg, Ethan Allen Weinberg, Rodney S. Wyman, Sterling C. Wyman, Stanley Clifford Weyman, Allen Stanley Weyman, C. Sterling Weinberg, and Royal St. Cyr, was the greatest impostor of the age. His feats seem breathtaking even today, and he became a true popular hero, the darling of the multitudes. Anyone who questions the extent of his fame can only reflect that a new feat of Weinberg’s got more space in the New York press of the day than the funeral ceremonies of Rudolf Valentino. Each article that will be posted here reveals a piece of his life. By the time, your finished reading all you will be amazed by how much he truly got away with.

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.