Monthly Archives: Nov 2023

29 Nov 1923 – Mineralava Beauty Contest News

1996 – Shear Destiny: Yvonne Sapia’s Valentino’s Hair

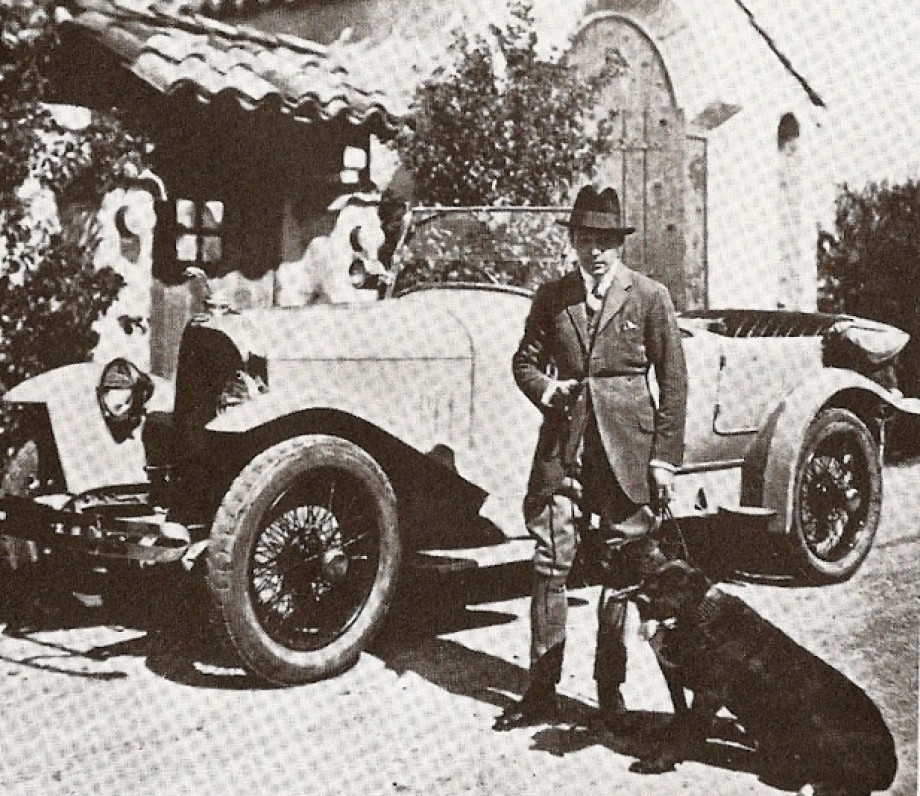

In 1926, a young Puerto Rican barber named Facundo Nieves is summoned by an exclusive Manhattan hotel to cut the hair of Rudolph Valentino, touching off a chain of tragic and compassionate events that comprise Yvonne Sapia’s imaginative first novel, Valentino’s Hair. Sapia creates a novel that is noteworthy for its creative narrative structure, its use of historical context, and its resonant motifs that allow the author to explore the consequences of forbidden love in a xenophobic and racist United States. This essay is a modest at- tempt to identify and discuss the implications of the issues that Sapia raises, as well as to examine the narrative structure and historical context within which she places them and the motifs which serve to illuminate them. More specifically, I will argue that Sapia’s use of his- torical materials and motifs enables her to move beyond the telling of a modern fairy tale with a familiar theme (the abuse of a magical talisman) toward an effective critique of race relations during a specific period of U.S. history. Paradoxically, her lack of attention to interracial issues during a subsequent period of U.S. history, also depicted in the novel, calls into question the novel’s optimistic resolution. The novel is composed of two interwoven narrative strands. The first is Facundo Nieves’s dying confession to his son Lupe of how he cut Valentino’s hair and later used the clippings to create a powerful aphrodisiac that ultimately proved fatal to the young woman he seduced. Sapia skillfully parcels out this story, interspersing it with the second, longer narrative which details Lupe’s coming of age, so that the reader does not learn until the penultimate chapter that this first- person narrative is Facundo’s dying confession. If the reader will bear with me, it is necessary at this point to summarize briefly the key events of Facundo’s story. It is 1926, Facundo Nieves operates a small barbershop in a first- class Manhattan hotel where one hot, summer day he is called by the front desk to give one of the guests a haircut. Upon his arrival at the hotel room, Nieves is stunned to find that his customer is Rudolph Valentino, one of his movie idols. As Nieves cuts the star’s hair, Valentino confides in the barber and tells him, “You do not realize it, but you are cutting away at my life too, time leaving me like mo- ments falling to the floor”. When the haircut is finished, Valenti- no gives him a hundred dollar bill, compliments his work and departs, while Nieves, “like a madman,” gathers up the clippings of Valentino’s hair. A few weeks later, Valentino collapses, is hospitalized and under- goes surgery for an unnamed illness. His condition worsens and Nieves is drawn by some instinct to the hospital where he is allowed to shave Valentino, whose last words to the barber are “cuida el pelo,” take care of the hair. The next day Valentino is dead and Nieves, un- nerved by the star’s final words to him, consults one of the local bru- jas (literally a witch, but more properly a sort of folk healer). The bruja tells Facundo that the hair is “the most powerful aphrodisiac” she has ever seen and she instructs him in its use, but warns him that it also has the potential to be misused. Facundo then learns the whereabouts of Valentino’s body and is given a pass admitting him to a private viewing later in the day. As word of Valentino’s death spreads, an unruly crowd gathers outside the funeral home and it is in this chaos that Nieves bumps into the young white woman he has long desired but who has consistently rebuffed his attentions. As they gaze upon Valentino’s body, Facundo whispers to her that he has some of Valentino’s hair and she accompanies him back to the barbershop where Nieves allows her to see and touch the hair. Suddenly she swoons and Nieves revives her with some rum into which he has mixed the aphrodisiac made from his blood and Valentino’s hair, a potion of which he also partakes. The effects are immediate and dramatic. As they make love in the barber chair, the woman calls out Valentino’s name and appears to lose consciousness a second time, even as Nieves continues to make love to her. Suddenly, he realizes that she is dead, that he has killed her and, in the novel’s most disturbing scene, Nieves still under the spell of the aphrodisiac-penetrates the woman a third time. As the effect of the aphrodisiac wears off, the horrible enormity of his actions settles upon Nieves. He slashes at his legs with a razor, becomes violently ill and loses consciousness. When he comes to, he manages to call his friend Mangual, who convinces the barber that his role in the woman’s death must be covered up. With the help of two Puerto Rican nationals, the dead woman is smuggled out of the hotel and her death made to appear the suicide of a woman dis- traught over the death of Valentino. The ruse is successful; foul play is not suspected and Nieves is never implicated in her death. Thus, ends the narrative timeline of 1926, all of which Nieves confesses his son Lupe on his deathbed in 1960. The second major storyline, told in the third person, relates coming of age in 1950s New York, as he learns about life’s hardships and ultimately is forced to reassess his father and the legacy bestowed upon Lupe. Through his eyes we see portraits of different family and community members and learn something of their gle and suffering, as well as the elements that bond them together. this sense, Sapia uses Lupe as a camera lens through which she ates snapshots of his extended family, creating of the novel a family album of the Puerto Rican community in The Bronx. This narrative structure, alternating between two prominent ries and two distinct voices, allows Sapia to achieve certain effects well as to explore different themes. Facundo’s dying confession which is disrupted by the story of Lupe’s coming of age-is used generate suspense and drive the narrative: the reader is anxious know what Facundo will do with the hair. But the confession is also used to focus attention on particular themes: issues of social power, responsibility, and the consequences of abusing such power. Lupe’s coming of age, on the other hand, allows Sapia to portray a commu- nity of people as seen through the eyes of one of its members who is learning how to function within it. There is also a third, less promi- nent narrative voice, most clearly visible in the chapter “Mythology of Hair,” that is scholarly, detached and almost clinical, and moves from scientific authority to mythological authority. Here, Sapia discusses common beliefs in the supernatural power of hair, one in stance of the magic and folklore that appear throughout the book and are shared beliefs in the Puerto Rican community. One of the myths discussed in this chapter is the idea that hair contains an individual’s essence and that the cutting of hair robs a person of some of his or her strength and vitality, as in the biblical story of Samson and Delilah which Sapia mentions. As she writes in the novel, “Said to have magical powers, its removal disturbs the spirit of the head, the soul of the body. The notion is universal that a person may be bewitched by means of clippings of hair”. This is precisely the notion that Sapia dramatizes in her novel in order to comment upon the very human need to possess what one desires, an attitude facilitated by the hedonism characteristic of the Jazz Age. The story of Valentino and Facundo’s use of his hair is very much linked to the historical time frame of those events. In many ways, Facundo’s actions, Valentino’s actions, and Valentino himself mirror the era. From the very outset of the novel, Sapia is careful to emphasize the 1920s as a distinct historical period: “In 1926, I was young, and I was a part of a world filled with such life, a world which was eating at its own edges without being satisfied. The Roaring Twenties they didn’t roar, Lupe. They swelled with passions. They danced, and I danced with them”. Facundo’s words here, as he begins his confession to Lupe, are ironic, for by the time the read- er reaches the conclusion of his story, she will have witnessed the dance of the 1920s, become a mob scene foreshadowing the violence of the decade to follow and like the insatiable appetite that Facundo attributes to the decade, he too will be driven by a passion he cannot control nor satisfy, as he causes a woman’s death and engages in necrophilia. Facundo’s characterization of the Roaring Twenties is just one ex- ample of how the first chapter of the novel is a crucial touchstone for the remainder of the text. Many of the events described in the opening chapter will be repeated in perverse fashion or with ironic intent later in the book and it is this doubling that gives the novel its resonance. Sapia foreshadows and underscores the importance of the rep- etition of events by means of an insistent mirror motif which she introduces almost immediately, following Facundo’s description of the 1920’s, on the narrative’s first page: “There were four large oval mirrors in the barbershop, two on one wall, two on the opposite wall. always thought they stared at each other like distant lovers, never permitted to kiss, only allowed to long for each other with their cool but secretive stares”. Not only do the mirrors placed directly across from one another so that an image caught between them replicated infinitely-suggest the duplication of events to follow as well as a doubling of desire (after luring the young woman to the barbershop and seeing her reflection in the mirror, Facundo will comment, “Now I had two of her”, their description here as “distant lovers, never permitted to kiss,” strikes the first note of the theme of forbidden love which motivates the barber’s actions later in the book, including both his decision to seduce the woman and his resolve to cover up the circumstances of her death. Mirrors are also used in the novel as a familiar device to suggest another persona latent in the viewer or as a sort of oracle that reveals the true self in a world and era obsessed with appearances. For example, as Facundo rides the elevator up to Valentino’s hotel room he glimpses his reflection in a small mirror and is surprised by what he sees: “And for that moment I thought I saw someone else. Someone who was walking towards me from another place we held in common”. And, significantly, Facundo’s first glimpse of Valentino is in a mirror with the star’s reflection alongside his own, suggesting a union of sorts and foreshadowing the ways in which Facundo’s destiny will become linked to Valentino’s. In Valentino’s case, mirror is used to suggest the disjuncture between his private self his public persona. As Facundo prepares to cut his hair, Valentino asks him to help with the man in the mirror and Facundo describes Valentino as staring “directly into the eyes of the pitiful man thought he saw in the mirror”. He continues, “I began to and disguise that perfect face, slowly, with compliance, like an complice to the development of the belief in one god” two lines suggest the extent to which Valentino’s carefully fabricated image governed every moment of his life. As Gaylyn Studlar has ed, accounts of Valentino’s early life were rewritten numerous by Hollywood publicity agents in repeated attempts to sustain popularity. In the following passage, we can see that Facundo nothing about any ideas or feelings that do not coincide with Valentino created through filmic discourse and, in fact, he will what he can to sustain that persona. He characterizes Valentino “a man who was a great lover, not a great philosopher. I didn’t to hear philosophy. I wanted to know about the desert at night, ride of the four horsemen, the posture of the tango”. Would too far-fetched at this point to suggest that Facundo’s fascination with Valentino is not unlike the mood of the public during 1920s-xenophobic and hedonistic, wishing to immerse itself in tasy in order to forget the horrors of World War I and ignore creasing unrest in postwar Europe? As noted above, Sapia’s novel contains many significant events that are “mirrored” or replicated at other chronological moments the narrative. One of the most interesting is related to Facundo Valentino at their first encounter. While the young barber cuts hair, Valentino tells Facundo of a bizarre incident that occurred hotel in California: an elderly woman sent to give him a manicure dropped dead just from looking upon him; Valentino had unleashed a sexual power that he couldn’t control. And although Valentino’s role in the death is covered up with the co-operation of the management and he is never publicly implicated, he must continue to live with the knowledge that he caused the woman’s death. do’s reaction is recounted years later to his son: Lupe, I was suddenly caught between laughing and crying. The poor man had a power he couldn’t control, and here I was absolving him his sin, listening to his confession like a priest in my white smock. now he was to do penance, he was to give something up to me. would raise my chalice of shaving cream and lift my silver razor to light and strip away Facundo’s reaction is revealing on a number of levels. First, sumes a position of power, likening himself to a priest hearing fession in a sort of spiritual transaction that sanctions his something from the penitent. This is a clever way of rationalizing later actions, the taking of the hair and the fashioning of the clippings into a love potion. Secondly, it foreshadows the later scene at the pital in which Nieves will again feel himself placed by Valentino the position of a priest administering a sacrament, this time the rites. But most importantly, Valentino’s confession to Facundo repeated by Facundo and Lupe, just as Nieves, like Valentino, find himself unleashing a sexual power he cannot control, resulting in a woman’s death. And, as in the first episode, the involvement the man responsible for the death will again be covered up, an which will torment him until he is able to confess. Like the mirrors in the book, the profession of the barber takes on many meanings and is crucial to Facundo’s sense of self and to the decisions he makes. The barber, with his razor so close to the skin, cannot afford a careless moment. However, when the barber does his job well, he becomes a type of physician or healer, making his patient feel better: “I was a kind of doctor. What I did helped people ride a stream to slow recovery, to arrive on the shore of something new, something which was hidden from sight. A secret place. A secret person”. Notice that again, we have a duality characteristic of Sapia’s narrative technique: if the mirrors are represented as devices which may reveal that dark side which is hidden within all of us, Facundo’s comments suggest that the barber’s ministrations bring to the surface that which is good but hidden within the individual. But if the barber is a kind of physician, he is also a kind of priest. Like a priest, Facundo listens to the confessions of his clients and grants them absolution. As already noted, Valentino confesses to Facundo twice. Moreover, the doctor and priest roles are combined when Facundo visits Valentino at the hospital. He is mistaken for a doctor and allowed admittance to Valentino’s room, where the dying movie star asks him for a shave that they both sense will be his last. Facundo is frightened and, in a comment that prefigures the macabre events to follow, recalls, “I had never shaved a dead man [before]”. The barber has become doctor, priest and mortician, and al- though the experience initially frightens Nieves, over time it gives him a sense of power and privilege that emboldens him to use Valentino’s hair for his own ends: I was the man who cut Valentino’s hair and learned of its power. I was the man who had shaved Valentino in his last hours. I knew him in a way no one else on that street knew him. And Valentino had trusted me with the last hours of his life. When the end came for him, he alone except for his three doctors and two nurses. He had lost con- sciousness sometime after I saw him, and the doctors had called in priest to give him the last rites. He was a priest from Valentino’s little town in Italy. Yet the truth is he had already received his last rites; had received the rites from me. Finally, the barbering metaphor establishes a tension that Sapia exploit: barbering is extremely pleasurable and sensual yet it potentially harmful if not done properly: these two extremes are arated only by the edge of a razor, and that boundary is crossed tragic ending to the novel which takes place, not coincidentally, barbershop. Facundo’s fantasy encounter suddenly becomes grotesque episode of necrophilia and self-mutilation. In her essay “Pleasure, Ambivalence, Identification: Valentino Female Spectatorship,” Miriam Hansen has noted that Valentino often viewed by biographers and cultural critics as embodying ongoing crisis of American cultural and social values” triggered World War 1. In particular, Hansen emphasizes the crisis gender relations in the United States that arose as large numbers women entered the work force and as they became increasingly portant players in a consumer economy. Thus, Hansen continues, Valentino emerges within the fractured cultural terrain created struggle between “traditional patriarchal ideology on the one and the recognition of female experience, needs and fantasies other, albeit for purposes of immediate commercial exploitation eventual containment”. Not only does Valentino, in a sense, into being as a cultural phenomenon because of these contradictory forces, but he comes to embody them or rather embody their product (the change in gender relations) to such a degree that he becomes flashpoint for opposing sides on that issue. Few popular icons polarized the men and women comprising white society to the that Valentino did. With a consistency that is nothing less than ishing, Valentino aroused contempt from men, while women whelmingly adored him. Studlar cites the notorious Chicago Tribune editorial (the so-called Pink Powder Puff attack) published month prior to Valentino’s death as emblematic of the “vitriolic mensions” of the male discourse on Valentino in the 1920s. Do women like the type of “man” who pats pink powder on his face a public washroom and arranges his coiffure in a public elevator?…a strange social phenomenon and one that is running its course not only here in America but in Europe as well. Chicago powder puffs; London has its dancing men and Paris its gigolos. with Decatur; up with Elinor Glyn. Hollywood is the national school of masculinity. Rudy, the beautiful gardener’s boy, is the prototype the American male. Hell’s bells and if the editorial and its subsequent notoriety suggest the to which American men believed Valentino represented a dangerous erosion of traditional ideals of masculinity and subsequent male power, the riots by distraught fans at his New York funeral, mostly women, as well as the scorn with which the New York Times ported their mourning, gives an even more dramatic sense of vision between male and female responses to Valentino in post-America. In order to understand this polarized, reaction to Valentino, it is useful to recall, as Hansen does, predominance of sadomasochistic scenarios in Valentino which the star is dominated by other men and women as often dominates the female love interest in the film’s narrative. Hansen also notes the “systematic feminization of his persona” through the use of exotic costumes and mise-en-scene, as well as by casting him within the film’s narrative as a performer. The outward response of a male audience to these conventions is probably not surprising. As Hansen remarks, “The vulnerability Valentino displays in his films, the traces of feminine masochism in his persona, may partly account for the threat he posed to prevalent standards of masculinity”. Conversely, Hansen speculates that: However complicit and recuperable in the long run, the Valentino films articulated the possibility of female desire outside of mother- hood and family, absolving it from Victorian double standards; instead they offered a morality of passion, an ideal of erotic reciprocity. In focusing pleasure on a male protagonist of ambiguous and deviant identity, he appealed to those who most strongly felt the effects-free- dom as well as frustration-of transition and liminality, the precari- ousness of a social mobility predicated on consumerist ideology. But the case of Valentino as cultural marker is of course more complicated than mere sexual politics; there is also his ethnicity or “racial difference” to consider. Hollywood dealt with Valentino’s otherness in filmic texts by consistently casting him in exotic, costumed dramas which, as already noted, exacerbated the perception among white American men that he was effeminate, yet both reactions turn on the intersection of race and gender and suggest the degree to which the dominant culture was both fascinated and threatened by the sexuality of non-white men. The romantic/sexual union of the characters Valentino played and the white female leads in his films could place only within the confines of the exotic and the ahistorical, tings which paradoxically emphasized and sanitized his otherness. Indeed, the very term Latin Lover-which Valentino is thought personify-is a distillation of this paradox, invoking myths sexual appetite and prowess of non-white men, while giving its ject a generic marker of classical connotation that keeps such overdetermined sexuality at a safe distance. Such strategies of containment become less surprising when one recalls that Valentino reached peak of his popularity during one of the most xenophobic periods U.S. history. But as white male reaction against Valentino intensified, the film industry found such strategies were no longer enough. sponded by attempting to create a new Valentino myth, that immigrant from humble origins who, through hard work, reaches pinnacle of success in the Melting Pot. As Studlar comments, this fort to “mainstream” Valentino was to a large extent offset by publicity imagery that visually insisted on capitalizing on eroticism unveiled”. The outcome of this conflict between peting racial and sexual ideologies was predictable, if bizarre: Holly- wood churned out a spate of copycat films about Latin Lovers, this time played by Anglo actors like Douglas Fairbanks, Ronald man and John Barrymore . And as the Latin Lover were co-opted by Anglo actors, “the assignment of pejorative nine and racist traits to Valentino intensified”. To summarize, the response to Valentino on the part of white was so hostile because not only did his persona represent a departure from traditional WASP norms of masculinity, it also engaged about sexual relations between non-white men and white women. Hollywood attempted to ameliorate those fears by a discourse of ex- oticism that made such taboo relationships safe, just as the term Latin Lover precisely connotes such forbidden love made safe by the exot- ic as much as it suggests the fusion of masculine domination with courtly manners. As Valentino’s popularity with white female moviegoers increased, so did the level of hostility toward him from white men. In the context of Sapia’s novel, it is significant that is, like Valentino, a non-Anglo immigrant to the United unlike the majority of Anglo men, an avid fan of Valentino. suggested earlier, Facundo’s possession of Valentino’s hair allows him to possess some of the star’s power over women locks him into repeating the star’s misfortunes, we can that argument with the observation that Sapia portrays traction for a white woman as a socially prohibited one, due to the same attitudes that created such animosity toward Valentino. Signifi- cantly, it is the fear of such animosity and racist reprisals that lie be- hind the decision to cover up the circumstances of the woman’s death. And there is another bizarre coincidence between the fates of Facundo and Valentino: the outpouring of grief by Valentino’s fans after his death and especially their attempt to glimpse and touch the star’s corpse as it lay in state is, as Hansen suggests, a figurative kind of necrophilia: The cult of Valentino’s body finally extended to his corpse and led to the notorious necrophilic excesses: Valentino’s last will specifying that his body be exhibited to his fans provided a fetishistic run for buttons of his suit, or at least candles and flowers from the funeral home. Significantly, it is within such an environment that Facundo meets the woman with whom he will literally engage in necrophilic excess; the hysterics at Valentino’s funeral are a figurative kind of necrophilia that mirror Facundo’s literal practice of it. And, Valentino’s funeral, as dramatized in the novel, is important for another reason as well. His body is guarded by Mussolini’s Italian fascists, foreshadow- ing the consequences of American isolationism and racism, just as the rioting and chaos of the funeral crowd foreshadows the violence and chaos of the war to follow. It is extremely ironic that Valentino, who rose to fame as a figure who could be used interchangeably in a variety of ethnic roles, would be guarded by fascist soldiers committed to a philosophy of ethnic purity. Sapia skillfully represents Valentino as a cultural icon that stands in ironic opposition to the fascist ideas of ethnic purity that are gaining currency in Europe and in some quarters of the United States. It is through such skillful use of historical context that Sapia enables Facundo’s story to operate as not just a modern fairy tale with a familiar theme, but as a critique of racist and sexist ideologies during a specific period of U.S. history. Another issue needs to be explored here, namely, Facundo’s fatal seduction of the young, unnamed woman and his willingness to cover up his role in her death. Although Facundo realizes he is responsible for her death and initially wants to tell the police what happened, he is persuaded by Mangual that given the racial climate, to do so would be to ensure his own eventual execution. As Mangual puts it: You are a Puerto Rican, Nieves. You are not welcome in Nueva York. You are an outsider. In the eyes of the Americans you just killed an American white woman, a white woman they would tell you, you never should have been with. What do you think they will do to you? They’ll say you lured her here, Nieves. They’ll say you sexually attacked her her. They’ll say you murdered her. …You feel guilty, of course. don’t blame you, Nieves. But look what they do to immigrants, to foreigners like us. For Christ’s sake, look what’s happened to those two Italians, Sacco and Vanzetti. Take it from me, hombre, they’re two men. And you will be too. They’ll crucify you, Nieves, and they’ll your balls off and shove them down your throat to make sure you dead. This argument is a bit slippery. While the white society of the racist and very probably would react as Mangual suggests (as the erence to Sacco and Vanzetti reminds us), such a position glosses over the fact that Nieves did lure the woman to his barbershop, drug her for the purpose of taking advantage of her, did sexually tack her and did cause her death. Nor does Sapia ever provide dence to suggest that racist sexual taboos were behind the woman’s lack of interest in Nieves. Consider also, that even after this tragedy, Nieves continues to use the talisman, seducing at least two women with it. He admits to his eldest child, Barbara, that he “magic” to cause his second wife to marry him and it is intimated that years later, shortly before his death, he uses the hair to obtain wife for his friend Pancho. Yet, despite attempts to rationalize tify his crime and attempts to use the talisman benevolently, do’s role in the woman’s death and his continued use of the talisman for personal gain clearly haunt him. Ultimately he is compelled by guilt to give an accounting of his actions. Significantly, the catalyst for Facundo’s confession is Valentino himself. After watching one of Valentino’s movies on the late late show, Nieves suffers a seizure and slips into a coma, during which time he mysteriously confesses his actions and his culpability to his son. The importance of this act is clear, as Facundo dies just moments after completing the confession, the final words of which suggest that he is now at peace: “Now, my boy, good-bye, good-bye. There’s a little boat waiting for me. I hear the dew falling in the rain forest. I hear voices echoing in the dark cool coves. The earth smells like a good place. Recuerdame, Lupe. After Facundo’s death, Lupe buries the last remnants of Valentino’s hair with his father in a gesture that suggests that al- though the father and son may be one, as Facundo was fond of saying, the son is not destined to repeat the mistakes of the father. Moreover, Sapia represents the idea that no one is beyond redemption. Nevertheless, there is something about this tidy ending which rings a bit hollow. To uncover the source of this dissatisfaction, I believe it is necessary to consider Lupe’s story in relation to his father’s. Significantly, most of the scenes in which Lupe is present have to do with his coming of age. He witnesses the tragic deaths of neighbors in a fire and learns that unrequited love can drive men to kill them- selves. He witnesses the unhappiness of immediate family members: his mother, who is saddened to tears by the loss of her youthful beauty; the fear of motherhood of his young, pregnant aunt Miriam, whose boyfriend has left her; and the cynicism of his grandmother Sofia, whose children have died at young ages. And he learns that his father and uncle were thrown out of their parents’ house when they came of age. However, although Lupe empathizes with his relatives, their experiences do not make him timid or fearful. Instead he draws strength from their experiences. All of this is made possible because Lupe remains firmly grounded in his Puerto Rican community. Yet, this insularity is precisely the element that causes the ending of the novel to appear overly optimistic. Lupe’s experiences have all taken place within the confines of that tightly-knit Puerto Rican communi- ty and he has been completely sheltered from any contact with the world outside of it. Early in the novel, Sapia addresses Lupe’s sheltered upbringing in an intriguing scene in which his stepsister Barbara refers to him as “colored,” a term that puzzles Lupe. To him, Barbara’s whiteskinned, rosy cheeked daughter is more colored than he is. However, after this childhood incident, Lupe does not have any more interaction with anyone from outside of his community. It is this lack of attention to relations between Puerto Ricans and other ethnic groups in Lupe’s narrative that leaves the reader with some reservations regarding Sapia’s suggestion that Lupe will not re- peat his father’s mistakes. Moreover, given the skillful treatment of race relations in Facundo’s narrative, the lack of attention to interracial issues in Lupe’s story stands out as a noticeable oversight. While the depiction of the Puerto Rican community as a source of strength, comfort and knowledge for Lupe is powerful and moving, his isola- tion from the outside world is disturbingly similar to the xenophobia that Sapia critiques so well elsewhere in the novel.

You must be logged in to post a comment.