Posts Tagged With: Rudolph Valentino

“I do not care …

“I do not care for money made easily. It is not lasting I know. I do not care for friends made easily. They are not lasting I know. I do not care for anything that comes easily. It is never lasts I know. But I fell in love with you easily. But not lastingly you know.”–Rudolph Valentino , 14 Jan 1924

“When …

“When asked why she married Valentino, she replied, “It was simply a case of California, the glamour of the Southern moonlight and the fascinating love-making of the man.”–Jean Acker, Former Wife of Rudolph Valentino

27 Aug 1930 – Rudolph Valentino owed some money

A minor Hollywood sensation has been caused by the suit which Alberto Guglielmi and Maria Strade brother and sister of the late Rudolph Valentino have filed against George Ullman. They charge Ullman with mismanagement of the estate and diverting large sums of money for his own use. Ullman, in the answer he has filed to the charges, says that, far from mismanaging the estate, he found it in a debt-ridden condition and spent years ironing it out. It was Valentino who wrecked his own estate, Ullman claims, for he died leaving debits of over $60,000 into a surplus of $100,000 to be distributed among the heirs. A court hearing will take place at the end of this month, and a decision reached as is whether Ullman shall be permitted to continue as manager and executor of the estate.

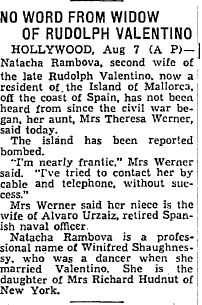

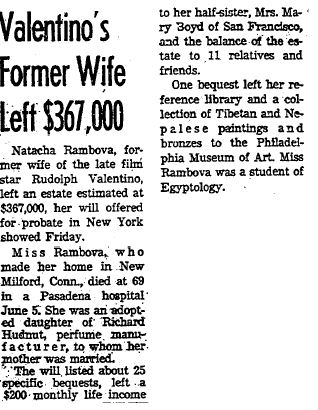

18 Jan 1933 – Miss Rambova Home Ransacked

Thieves entered the Majorca home of Natacha Rambova, former wife of Rudolph Valentino and ransacked the establishment. They stole a revolver but did not steal any jewelry. Authorities investigated on the theory that the thieves were looking for papers. Miss Rambova would not comment.

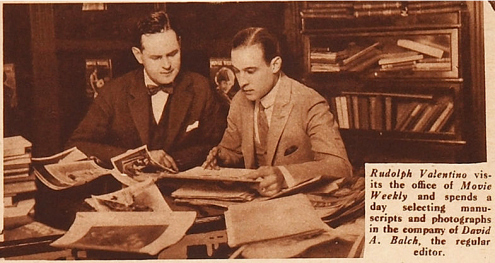

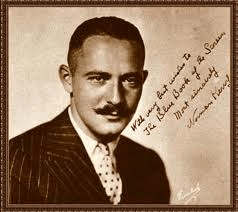

24 Oct 1926 – Valentino Manager Writes Valentino’s Story

A book dealing with intimately with the late Rudolph Valentino was issued yesterday by Macy-Masius, publishers. The book by S.George Ullman, for many years the film star’s manager. It is called “Valentino as I knew him.” A preface has been written by O.O. McIntyre. Mr. Ullman traced Valentino’s career and devoted much space to explaining his last illness. On the question of whether Valentino was engaged to Pola Negri at the time of his death, Mr. Ullman said that “he never told me so, and I never asked him”. The author however, added that Valentino had vowed never to re-marry until he had finished his movie career.

“The biggest th…

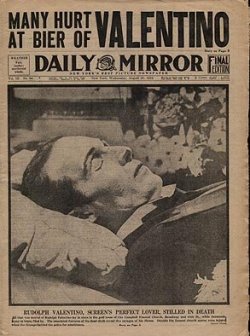

“The biggest thing that Rudolph Valentino did was die”..–Alice Terry, Lead actress Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse on his death.

7 Feb 1948 Restauranteur Holds Valentino IOU

Manhattan restauranteur Sam Slavin still holds an IOU from Rudolph Valentino for $10.00. He lent Rudy money when the great silent film star worked in Slavin’s place for $12.00 a week. Valentino many times tried to buy it back, but Slavin always refused to sell. And its still there, framed, on the wall of the restaurant.

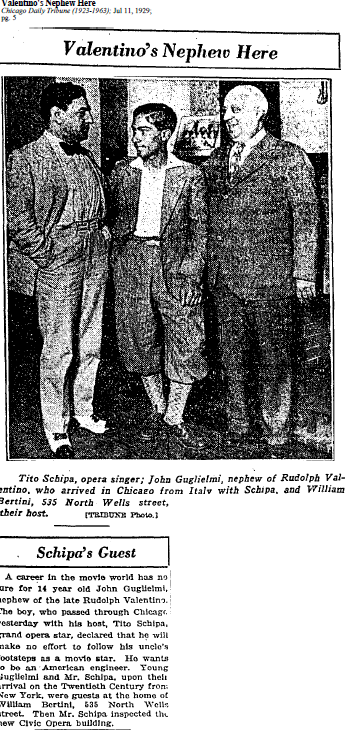

8 Oct 1927 – A New Valentino?

Rumors that Alberto Valentino is being groomed to succeed his late brother, Rudolph Valentino, on the screen have been received. It is stated that-Gugiielmi has submitted to vain operation of plastic surgery. Alberto Valentino’s face, it is said, has been re-modeled on lines resembling those of the late screen idol, his bold and belting nose being altered to a classical shape. Guglielmi came to the US a year ago to attend his brother’s funeral

23 Mar 1965 – Mae Murray Died

Mae Murray, the glamorous, famous, and beautiful Hollywood icon who told the press, “Once you become a star, you are always a star!” was found destitute at the age of 75, aimlessly wandering the streets of St Louis, Missouri.

Marie Adrienne Koenig was born of Austrian-Belgian parentage May 7, 1889, in Portsmouth, Virginia. Years later, she told everyone she was born Mae Murray, “On my father’s boat, whilst we were at sea.”

The imaginative and ethereal Mae also stated that a great-grandmother had raised her, placing her in several European convents. While in one of the churchyards, she told, she was punished for dancing in the gardens at night pretending to be a firefly and striking matches as she fluttered through the grounds.

In 1906, the stunning young performer made her Broadway debut in About Town. Murray then danced in three editions of the Ziegfeld Follies; in 1907 as the partner of the famous Vernon Castle, and alone in 1909 and 1915. The dazzling Murray also appeared in numerous other musical comedy roles and headlined performances in fashionable New York supper clubs.

Still in her teens, Mae married W.N. Shwenker Jr., the son of a millionaire. She got out of that marriage with some funds, and secured her second husband, producer Jay O’Brien, a stockbroker and Olympic bobsled champion known as the “Beau Brummel” of Broadway, and who proved to be helpful in Murray’s stage career.

Only days after their highly publicized wedding, and soon after her involvement with Rodolfo Guglielmi, a dancer billed as Signor Rodolfo who was later to become Rudolph Valentino, in the De Saules affair in New York in which Valentino’s socialite lover shot her husband to death for him, she dumped Jay and had the good fortune to marry Hollywood director Robert Z. Leonard. They lived in a beautiful apartment at 1 West 67th Street in New York. With this union she found her true destiny as a movie queen, and made her film debut in the east coast filmed To Have And To Hold (1916). Blonde and sensuous, standing five-foot-three with blue-gray eyes, the hideously arrogant Miss Murray was completely obsessed with her beauty.

She became famous for the extreme and unusual application of her lipstick, soon copied by millions of fans, and was widely known as “The Girl With The Bee-Stung Lips,” a title of which she tried to claim exclusive copyright. Often seen zipping through town in her custom-built Canary Yellow Pierce Arrow, the star was always opulently dressed and dripping in jewels. Once, reportedly, when purchasing some jewelry at Tiffany’s, she paid for it with tiny bags filled with gold dust.

In Hollywood, Murray’s films included The Right To Love (1920), The Gilded Lily (1921), The French Doll (1923), Jazzmania (1923), Circe The Enchantress (1924), and Fashions Row (1924). One critic wrote of her film Mademoiselle Midnight (1924) as “More of Mae Murray’s fuss and feathers thinly described as acting. This time Mae has her histrionic hysterics in Mexico. The general blurred impression given by the picture is this: Mae Murray-large mountains-Mae Murray-midnight love trysts-Mae Murray-a weird fandango by somebody described as a screen star-Mae Murray-cowboys having spasms-Mae Murray.”

The public loved her. The exquisite and elaborate costuming she insisted upon often brought her movies in way over their budget. Yet, Mae Murray danced her way to even greater heights of fame in Erich Von Stroheim’s The Merry Widow (1926). During the filming, their artistic differences and verbal brawls became an infamous Hollywood legend. She often referred to her director as “that dirty little Hun,” which she brazenly called him in front of a thousand extras magnificently dressed for a ballroom scene.

One day, her co-star John Gilbert walked off the set during one of his own disputes with Stroheim, and the tenuous Murray chased after him to the parking lot while wearing nothing at all but her shoes. Also during filming, the very young Joan Crawford often watched and studied Murray intently, learning how to be a star. The Merry Widow became MGM’s first big box office hit. The movie was extraordinary, with lavish production values and gorgeous photography. Mae Murray gave the best performance of her career, and then toured the nation holding lucrative performances of her Merry Widow Waltz. She followed this film success with Valencia (1926).

One of Murray’s glamorous screen rivals, Gloria Swanson, married the Marquis Henri de la Falaise de Coudray, and became royalty. This infuriated Murray, who wanted to become royalty too. Dumping her third husband, Murray found and married broke Ukrainian Prince David Mdivani in 1926. His royal status in his native Georgia was never truly established.

The headline producing ceremony included Rudolph Valentino, who died that same year, and his paramour, sultry star Pola Negri, Mae’s other screen rival, as matron of honor. Not to be outdone by Princess Mae, and not so long after the professed love of her life died, Negri married David’s equally broke brother Sergei in 1927 and became Princess Pola, as well as Princess Mae’s sister-in-law. The two Princesses were completely committed to the important cause of showing the world they were above mere mortals.

With Prince David, Murray had a son named Koran. Princess Mae was rarely photographed without her head swung way back, looking down her nose at her adoring husband and fans. She stated to the press, “I’ve always felt that my life touches another dimension.” When her marriage went bad, her doctor told her, “You live in a world of your own.”

Mae’s sweet Prince became her manager, took over her finances and insisted she walk out on her MGM contract to work independently. Soon, she found it difficult to get any roles at any studio. Sound film hit Hollywood. Her final movie was Bachelor Apartment (1931) with Irene Dunne, and the world was not pleased when it heard her voice.

By 1933, she was broke, ordered by the court to sell her opulent Playa del Rey estate to pay a judgement against her. Prince David now found her useless, and they soon divorced. In 1934, Murray declared bankruptcy. By September of 1936, she lost custody of Koran, and the former movie temptress was spending several nights sleeping on a park bench in New York, where she was arrested for vagrancy. The owners of the 67th Street residence where she resided luxuriously years before allowed her to live in the maid’s room of the building.

In 1950, back in California, Mae Murray was asked her opinion of the great film Sunset Boulevard, which starred her old rival from the silent film days, Gloria Swanson. Mae stated, “None of us floozies was ever that nuts.” Ironically, Mae was the nuttiest of them all. Walking down Sunset Boulevard with her head thrown back even further than she had done in her youth, Mae created a smoother jawline, watching the sky as she carelessly moved towards treacherous curbs and posts.

At the numerous charity balls she would attend, Mae Murray would ordain the orchestra to play the theme song from The Merry Widow soundtrack, waltzing to it by herself until all the elegant guests left the floor. In 1959, a biography of her life appeared, The Self Enchanted by Jane Ardmore, but the public was not interested. In 1961, she appeared on a television program where she stated that the only present day movie star who matched the talents of her time was the handsome Steve Reeves, famous for playing Hercules.

In 1964, living off charity and devoted friends, the poor deluded Murray continually traveled by transcontinental bus from coast to coast on a self promoted publicity tour, hoping for a comeback in movies. On the last of these excursions, she lost herself during a stopover in Kansas City, Missouri, and wandered to St. Louis. The Salvation Army found her and sent her back to her small Hollywood apartment near the Chinese Theatre, paid for by actor George Hamilton..

Mae Murray’s millions of dollars had been spent during a bitter life filled with lawsuits over salary agreements, damages, divorces, and bankruptcies. Some of Mae’s old friends made sure the still regally dressed and bejeweled star spent her last days in peace at the Motion Picture Country House where she often told the nurses, “I am Mae Murray, the Princess Mdivani,” and died in peace March 23, 1965.

During the height of the depression of the 1930’s, which had wiped away many fortunes, Mae Murray gave an interview, lucidly describing the Gods and Goddesses of her Hollywood days. “We were like dragonflies. We seemed to be suspended effortlessly in the air, but in reality our wings were beating very, very fast

Source:

“Valentino said…

“Valentino said there’s nothing like tile for a tango!” — Norma Desmond to Joe Gillis in Sunset Boulevard (1950)

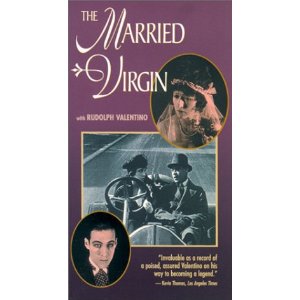

1918 – Synopsis of “The Married Virgin”

Mrs. John McMillan is having an affair, unknown to her husband and her stepdaughter Mary, with fortune hunter Count Roberto di San Fraccini. Overhearing a man threaten her husband with exposure for his connection with a murder unless he agrees to pay a huge sum of money, Mrs. McMillan conceives of a scheme with her lover the Count to acquire Mary’s dowry. Roberto informs Mary that in return for her hand in marriage, he will save her father from life in prison. Although desperately in love with Douglas, a young engineer, Mary agrees to the sacrifice, entering into a marriage in name only. Roberto continues his affair with Mrs. McMillan until, during an automobile ride, an accident occurs and she is killed. Roberto, fearing that he may be blamed, runs away. Mary then secures an annulment of her marriage to Roberto, thus freeing her to marry Douglas, the man she loves

The Married Virgin is an American film drama first released in 1918, directed by Joseph Maxwell. The film was scored by Brian Benison. It stars Vera Sisson, Rudolph Valentino, Frank Newburg, Kathleen Kirkham, Lillian Leighton, and Edward Jobson. It has also been released under the title: Frivolous Wives. It is a Maxwell Production, distributed by General Film Company. Film Length is 1 hour and 11 minutes.

1918 The Cast of the “Married Virgin”

Director Joseph Maxwell, Fidelity Pictures

Screenplay/Story Hayden Talbot

Cast Vera Sisson, Rodolfo di Valentini, Frank Newburg, Kathleen Kirkham, Edward Jobson, Lillian Leighton

Plot – Rudolph Valentino’s first film as a leading man where he plays Count Roberto di Fraccini, a fortune hunter having an affair with the wife of a wealthy older businessman. In order to save her wealthy father from disgrace and a possible prison sentence, a daughter agrees to marry the gigolo who’s been blackmailing him. What the daughter doesn’t know, however, is that the gigolo is actually in cahoots with her father’s new wife, a conniving schemer who plans to fleece her new husband for everything he has, then flee the country with her lover.

1923 Paul Poiret Clothing Designer to Natacha Rambova

Paul Poiret was the favorite clothing designer of Natacha Rambova who felt he understood her as no one else did when it came to making clothes that favored her flamboyant personality.

In 1879, Paul Poiret was born in Paris he interned at Jacques Doucet who was a famous couturier of the time. In 1901, he was hired by the famous Worth House of Design. In 1903, he set up his own Atelier of Poiret. In the early 1900’s which was considered one of Poirets influential periods in fashion he was interested in “The Orient” Russian and Cubism. Poiret claimed to have been a Persian prince in a previous life. Significantly, the first Asian-inspired piece he ever designed, while still at Worth, was controversial. A simple Chinese-style cloak called Confucius; it offended the occidental sensibilities of an important client, a Russian princess. To her grand eyes it seemed shockingly simple, the kind of thing a peasant might wear; when Poiret opened his own establishment such mandarin-robe-style cloaks would be best-sellers This had a great impact on Natacha’s own aesthetic which is what she became known for. In 1913, he came to NY and was a clothing designer to Cecille B. Demille. In 1923, Natacha first visited his Atelier which was documented in a Photoplay magazine article. His clothing displayed vibrant colors which managed to capture her personality. In Jan 1924, during another visit to his salon, Rudolph Valentino was quoted as saying that “he is the one costumier in Paris best suited to Natacha’s style, even temperament. We went to one or two other places and looked at their models, but for the most part they were wishy-washy things of pastel shades, with oddments of flowers here and there. Natacha cannot wear that sort of thing. She is not at all the type. She looks best in vivid colors, no one color over another, but all colors that are violent and definite. Scarlet’s, vermilions, strong blues, empathic greens, and loud voiced yellows”. Natacha’s next visit was Aug 1924; she came by his Atelier to pick up some dresses that she had ordered. In 1925, she staged a media event when she traveled from Los Angeles to Paris to pose for photographer James Abbe at famous clothing designer Paul Poiret’s salon. She modeled a pearl-embroidered white velvet gown and a chinchilla cloak, and declared Poiret her favorite couturier. In 1929, Poiret closed his Atelier because his aesthetics conflicted with modernism even though his designs back in the early 1900’s were advanced for the times. In 1944, Paul Poiret died in poverty virtually forgotten. However, through research a new generation has come to appreciate his genius in costume design. In 1927, when Natacha Rambova because a clothing designer in her own right, she did use Paul Poiret as an inspiration but with her own dramatic touch in the clothing that she designed.

“But if ever my…

“But if ever my belief in myself should utterly fail me. If the day should come when my struggle for my individual Right should wear me threadbare of further effort, then I should come to a garden place where the sky would ever be blue above me, where my feet would press soil as vernal and virgin as I could find, where, below me, under white cliff’s, the sea could sing me its immemorial lullaby. I think, there must, at one time or another, have been sailors in my family. For the sea pounds in my veins with a tune I still remember and I know that I could not have remembered it in this life I have lived”.–Rudolph Valentino

11 Feb 1923 – Rudolph Valentino is not Handsome

Rudolph Valentino— than whom there is not one more soul stirring— is ‘not’ handsome in the strict sense of the word. The back of his head is too straight up and down, and unless the camera gets him at just the right angle, his nose is too, broad for beauty. Yet he is the screen. idol of the feminine world. Ask half a dozen women why they find Valentino charming, and you will receive half a dozen different answers. A prominent screen artist in Los Angeles recently said: ‘I think Valentino is perfectly fascinating.’ ‘He looks as if you couldn’t believe a word he said to you. ‘Those gorgeous eyes, ‘another will say ‘Dark and enigmatic, like dull coal smoldering, yet ready to leap suddenly into passionate flame. They are undoubtedly part of his lure.’ Sometimes he looks like a small boy who is being abused, so that every woman wants to pat his shiny head and comfort him. Still, she knows perfectly well that he is .not, a small boy, and that it would be rather like patting dynamite-which, of course, makes him very fascinating.

Aug 1923 – Deauville

It’s late August 1923, Deauville, France and there is a huge excitement in the air regarding the arrival of Rudolph Valentino and his new bride Natacha Rambova. Seems that they are going to be stopping off in town for a quick visit and everyone is simply talking about them. It is a belated honeymoon they have already seen the sights in London and Paris. They will be arriving in three cars the first for the luggage, the second for secretaries and the last for the Valentino’s and their guests. They are staying in a villa rather than a hotel that is wise for privacy. That night the Valentino’s arrive at the Casino, take drinks, dinner, visit the baccarat rooms and watch the cabaret but are rather aloof and do not mingle much. Needless to say they cause a huge flutter. But gossip spreads like wild fire as usual. People are saying ‘they are in ill humour and not happy with the weather or their accommodation. They are also disappointed with the Casino, upset with the food and rather disdainful of all of us. Mrs. Valentino apparently has her nose stuck in the air and was heard to ask ‘where is the fashionable crowd?’ I can see no smart women and no smart men.’

“Auntie and my …

“Auntie and my sister have arranged to sit together in the back seat of the car so that they may not know the worst that the road (and again my driving!) has to hold for them. Natacha says that I am either neurotic about my prowess at the wheel, or else that I have a guilty conscience, else I would not dwell so constantly upon it. I tell her that my record speaks for me. I have nothing to say.” –Rudolph Valentino

“Valentino,” by H.L. Mencken

Unluckily, all this took place in the United States, where the word honor, save when it is applied to the structural integrity of women, has only a comic significance. When one hears of the honor of politicians, of bankers, of lawyers, of the United States itself, everyone naturally laughs. So New York laughed at Valentino. More, it ascribed his high dudgeon to mere publicity-seeking: he seemed a vulgar movie ham seeking space. The poor fellow, thus doubly beset, rose to dudgeons higher still. His Italian mind was simply unequal to the situation. So he sought counsel from the neutral, aloof, and seasoned. Unluckily, I could only name the disease, and confess frankly that there was no remedy – none, that is, known to any therapeutics within my ken. He should have passed over the gibe of the Chicago journalist, I suggested, with a lofty snort – perhaps, better still, with a counter gibe. He should have kept away from the reporters in New York. But now, alas, the mischief was done. He was both insulted and ridiculous, but there was nothing to do about it. I advised him to let the dreadful farce roll along to exhaustion. He protested that it was infamous. Infamous? Nothing, I argued, is infamous that is not true. A man still has his inner integrity. Can he still look into the shaving-glass of a morning? Then he is still on his two legs in this world, and ready even for the Devil. We sweated a great deal, discussing these lofty matters. We seemed to get nowhere.

Suddenly it dawned on me – I was too dull or it was too hot for me to see it sooner – that what we were talking about was really not what we were talking about at all. I began to observe Valentino more closely. A curiously naive and boyish young fellow, certainly not much beyond thirty, and with a disarming air of inexperience. To my eye, at least, not handsome, but nevertheless rather attractive. There was some obvious fineness in him; even his clothes were not precisely those of his horrible trade. He began talking of his home, his people, his early youth. His words were simple and yet somehow very eloquent. I could still see the mime before me, but now and then, briefly and darkly, there was a flash of something else. That something else, I concluded, was what is commonly called, for want of a better name, a gentleman. In brief, Valentino’s agony was the agony of a man of relatively civilized feelings thrown into a situation of intolerable vulgarity, destructive alike to his peace and to his dignity – nay, into a whole series of such situations.

It was not that trifling Chicago episode that was riding him; it was the whole grotesque futility of his life. Had he achieved, out of nothing, a vast and dizzy success? Then that success was hollow as well as vast – a colossal and preposterous nothing. Was he acclaimed by yelling multitudes? Then every time the multitudes yelled he felt himself blushing inside. The old story of Diego Valdez once more, but with a new poignancy in it. Valdez, at all events, was High Admiral of Spain. But Valentino, with his touch of fineness in him – he had his commonness, too, but there was that touch of fineness – Valentino was only the hero of the rabble. Imbeciles surrounded him in a dense herd. He was pursued by women – but what women! (Consider the sordid comedy of his two marriages – the brummagem, star-spangled passion that invaded his very death-bed!) The thing, at the start, must have only bewildered him. But in those last days, unless I am a worse psychologist than even the professors of psychology, it was revolting him. Worse, it was making him afraid.

I incline to think that the inscrutable gods, in taking him off so soon and at a moment of fiery revolt, were very kind to him. Living, he would have tried inevitably to change his fame – if such it is to be called – into something closer to his heart’s desire. That is to say, he would have gone the way of many another actor – the way of increasing pretension, of solemn artiness, of hollow hocus-pocus, deceptive only to himself. I believe he would have failed, for there was little sign of the genuine artist in him. He was essentially a highly respectable young man, which is the sort that never metamorphoses into an artist. But suppose he had succeeded? Then his tragedy, I believe, would have only become the more acrid and intolerable. For he would have discovered, after vast heavings and yearnings, that what he had come to was indistinguishable from what he had left. Was the fame of Beethoven any more caressing and splendid than the fame of Valentino? To you and me, of course, the question seems to answer itself. But what of Beethoven? He was heard upon the subject, viva voce, while he lived, and his answer survives, in all the freshness of its profane eloquence, in his music. Beethoven, too, knew what it meant to be applauded. Walking with Goethe, he heard something that was not unlike the murmur that reached Valentino through his hospital window. Beethoven walked away briskly. Valentino turned his face to the wall.

Legend has it that Charlie Chaplin, Rudolph Valentino and Douglas Fairbanks once raced each other down Hollywood Blvd, with the loser having to pick up the dinner tab at Musso and Frank’s

2012 – My Night with Rudolph Valentino

Years ago, after the closing night of a play I was appearing in, I decided to drive to Los Angeles to see a college friend. I rented a car and took the scenic route south, driving along State Route 1, a highway that rims the Pacific coast. It was a long and thrilling day trip, driving around the scenic mountain curves, ragged rocks, and through stretches of redwood forests. By the time I reached Hearst Castle and finished a tour in the late afternoon, I knew I would not complete the journey to Los Angeles that day, and was recommended a hotel further south in Santa Maria.

It was an old, historic inn located inland on the hot, dry stretch of a valley at the base of the Sierra Madres. The interior of the hotel lobby and meeting areas were decorated as if it were a pub in the English countryside, with dark wood paneling, somber rugs, oversized chairs, stained-glass windows and brass chandeliers. The management of the hotel had decided to play up its celebrity prestige—guests used to stop here en route to Hearst Castle from Los Angeles—and silent film movie-star memorabilia decorated the walls and the guest rooms were named after many who had stayed at the hotel: Charlie Chaplin, Marlene Dietrich, Jean Harlow and Douglas Fairbanks.

My room on the second floor, however, had been named after a local politician, with a window that opened out onto an interior courtyard that was shared by several rooms. As I drew the curtains closed, I noticed that the window was unlocked, and I bolted and tested it to make sure it was secure.

After a long shower and a change of clothes, I was hungry and headed downstairs to the hotel’s restaurant, but a wedding reception was in progress in one of the banquet rooms, so I settled in at the bar where it was quieter, ordered a drink and something to eat. From where I was seated I could see the other end of the bar and, as the summer daylight stretched its last breath out, the details of one of the customers seated alone near the door became more distinct. He was tall and slender, probably in his late twenties, and he had a sleek, elegant look about him—slicked-back black hair, a light stubble of beard, a strong sloping nose with flaring nostrils, and a prominent chin, and he was wearing a white shirt open at the collar with an unraveled bowtie draped around his neck. Because of his attire, I took him to be part of the wedding party. I shifted and squirmed on my bar stool, hoping he might notice me, but he seemed distracted and vacuous, intent on downing his drink, and I lost sight of him when a gentleman sat beside me at the bar and began to complain about the noise of the piano in the other room.

An hour later I stumbled up to my room, slipped out of my clothes and into a T-shirt and sweatpants. I considered watching television for a while, but I couldn’t find the remote control, so I flipped off the light and pulled back the curtains to look out at the courtyard.

It was empty and unused. The moon was high and strong and it gave my room an eerie blue glow and I drew the curtains together so only a small ray of light came into the room.

I was in a deep sleep when the knock at the door woke me. As I groggily got out of bed, I thought it might be the guy from the bar, come knocking for some companionship instead of handing out more complaints.

I flipped on the light and opened the door but no one was there. I was confused, bewildered and disappointed, the brighter light of the hall was exasperating, and I tried to brush the annoying disturbance away as the immature hijinks of one of the wedding guests. But as I moved to close the door I felt something move through me that felt like an ice-cold wind. A chill ran up my spine and along my arms.

The door closed and I turned back to the room and flipped off the overhead light. The moonbeam fell across the carpet again. That was when I saw him. The slick, black-haired handsome man I had seen earlier at the bar. He was substantive and real and I could not figure out how he had made it around me and into the room without my noticing him. He stood visible in the ray of moonlight and looked as if he were posing for a photograph, his nostrils slightly aflare. As my eyes moved from the window back to the man he began to dematerialize, as if he were on an episode of Star Trek and Scotty was beaming him to another place.

My heart was racing and I sat on the edge of the bed to gather my wits. What would the front desk think of me if I called them and told them I had just seen a ghost? Instead of reporting the incident, I drank a glass of water, checked that the window was secure and the courtyard was still empty, then went back to bed.

I spent the remainder of the night restless, tossing, sweating, fighting an erection as if someone had curled around me, locked me into a hold, and was trying to alternately smother or arouse me. There was a digital clock beside the bed that I watched change minute by minute. Sometime in the early morning I drifted off to sleep, because when I woke the sunlight striped the floor as it split between the curtains.

I rolled over and noticed the curtains were moving. The window was unlocked and opened and a breeze was coming into the room. I sat up in bed and looked quickly around the room to see if anything was missing. Nothing seemed disturbed—my wallet was in place, the car keys were where I left them. But in the center of the floor, exactly where I had seen the apparition the night before and where the ray of sunlight now hit the carpet, was a shiny silver object. I got out of bed and picked it up. It was a ring. Silver with a flat top and an engraved insignia. The sizing was small—it would only fit on my pinky finger. I didn’t immediately associate the ring with the ghostly vision I had seen the night before. At the time I found it, I was more concerned that I might have been robbed while I slept.

I slipped the ring into a small, top pocket of my knapsack I rarely opened, intending to hand it over to the front-desk clerk when I checked out. But that good intention slipped by me because I quickly forgot about it.

The ring stayed in the top pocket of my knapsack for years, forgotten, snug in its upper berth, traveling with me to London, Zurich, Tokyo and other not-so-far-off destinations. I only discovered it again when my boyfriend Kurt and I were in Fort Lauderdale and I was emptying the knapsack so that I could use it to carry a towel to the beach. Kurt looked at the ring, smirked and said, “What Cracker Jack box did this come from?”

I explained how I came to find the ring. Kurt thought my ghost sighting was hogwash. Kurt was all numbers; he managed a brokerage office and was also something of an elitist snob, but he could accurately assess the financial value of any item and he dismissed the pinky ring as cold, cheap steel. We were in the last throes of our relationship and to annoy him, I slipped the ring on my small finger and wore it for a few days, until we returned to New York and I noticed the metal had made my skin turn a sickly greenish-black. I placed the ring in a small ceramic bowl in the bedroom of my Chelsea apartment where I kept a set of formal cufflinks and shirt studs and only discovered it again one night when I was dressing for a formal-attire Halloween dinner party. I slipped on the pinky ring and during cocktails that evening, I told a small group of men my story of finding it only after witnessing a ghost the night before.

A young man said, “You might be the last person to boast that he slept with Rudolph Valentino.”

I laughed and replied that that was highly unlikely, but he reached into his pocket and pulled out his cellphone and took a picture of my hand with the pinky ring. I had never associated my ghost and cheap treasure with a celebrity phantom, but the young man said that Valentino had often been a guest at Hearst Castle and my description of the ghost seemed to match the actor’s. I found this young man charming and throughout the evening, in the various positions we found ourselves, he asked me in his most delightful bedroom voice about the name of the inn, the room number I had stayed in, what time of year I was visiting and on and on.

A week or so later, the young man emailed me evidence of Rudolph Valentino wearing the ring in several movie stills and publicity photos. I downloaded the pictures to my computer and saw it was a perfect match to the pinky ring I had in my possession. The engraving was unmistakable. Valentino is wearing the ring in photos with actresses Gloria Swanson and Agnes Ayres, in a portrait with his dog and beside a camel on the set of The Son of the Sheik, his final film. Valentino died at the age of 31, roughly the same age as the ghostly man I had seen. And the legendary actor in the photos looks exactly like the phantom I had seen in the bar and in my hotel room. The young man who had helped me discover this was a blogger and he said he wanted to write about my night with the ghost of Valentino. He contacted the owner of the hotel where I had stayed years before and discovered that several other guests had reported seeing a ghost in the room I had stayed in and that Valentino had been a frequent visitor to the inn. The blog post about the gay man who had slept with the ghost of Valentino went viral. I was more famous than I could possibly imagine, though I gratefully remained unnamed in the post.

Flash forward a few more years to when a reality TV producer contacted the blogger about Valentino’s ghost and the blogger gave the producer my name as the source of the haunting. When the producer called, I told her there wasn’t much to say about the ghost. I saw him; he disappeared. I shivered and sweated through a night with an erection that would not end. I could not even admit if Valentino—or his ghost—was a good kisser.

But the producer pressed on and asked if I would consider loaning the ring to film an episode of the TV show. I told her I no longer had it. And that was true. One morning not long ago I noticed it was gone—it wasn’t in the ceramic bowl. I remember looking around to see if anything else was missing from my apartment, but nothing was. Since I had last seen the ring I had had many visitors to my apartment: boyfriends, tricks, dates, even a hustler or two. Now, discovering and wearing the ring seems like a feverish dream I might have made up in my youth, and I wonder if my night with Valentino was something I had cooked up just to get attention. Only I am not that sort of guy. Instead, I imagine another man wearing that ring now—someone handsome, sleek, elegant, then one morning finding the ring cheap and tawdry and tossing it away. Something for the next man to find.

Source:

http://www.nextmagazine.com/content/my-night-rudolph-valentino

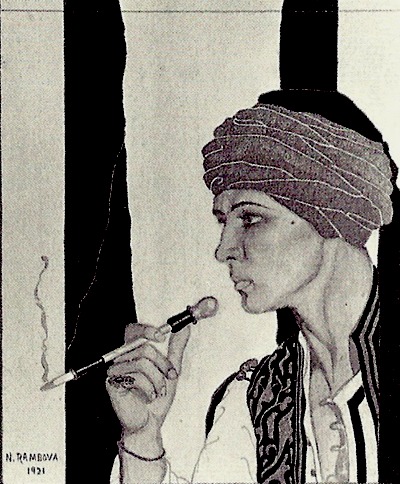

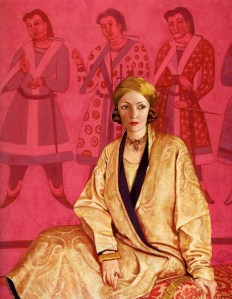

1931 – Natacha Rambova Painting by Svetoslav Roerich (Former Fiancee)

1917- 1939 The Romantic Life of Natacha Rambova

When conducting research for this article, I found there is still a great deal of undiscovered information that exists on Natacha Rambova. After all these years, there seems to be certain elements out there that do not want or like bringing things she has done in her past to light. Of course, this causes me to wonder what more intrigue is out there that she caused. Through reading what I can find on the Internet we all know she was not a people person. But a woman who knew what she wanted and went after it. One major discovery I noticed was Natacha was attracted to a certain type of man. Looking at pictures of Theodore Kosloff, Rudolph Valentino, Svetoslav Roerich, and Alvaro de Urzdiz all former lovers or husbands they all do seem to have similar features in face and temperament.

In 1917, the first relationship of Natacha Rambova was when she 18 years old. Natacha while studying ballet pursued her dance instructor. Theodore Kosloff, 32 years old, married and with a child. Eventually, she would discover that what started out as a grand passion one of mutual similarities the relationship was not what she thought it would be. Theodore Kosloff used Natacha’s talent as a designer and took credit for her designs. This was an abusive relationship from beginning to end.

In 1921, Natacha met her next relationship Rudolph Valentino who eventually became her first husband while working on the movie set of Unchartered Seas. From the beginning of this relationship until the very end Natacha assumed the dominant role. This relationship was totally different from her previous one. What started out as a satisfactory and mutual relationship this was not one of an equal partnership. Natacha cheated on Rudolph with a cameraman from her movie set on What Price Beauty that she was producing. In 1926, this relationship ended sadly in a divorce.

In 1928, Natacha Rambova met her next relationship; his name was Svetoslav Roerich in New York City. From research, they both lived in the same building, had close friends, some of whom also lived in the building. They share strong interests in esoteric teachings and even planned a school of esoteric teaching that was intended to teach all the important esoteric teachings of the world. They had a joint project with the organization of the Museum of religion and philosophy. Svetoslav Roerich was the President of this Museum and Natacha Rambova was Secretary-Treasurer. In 1929, I believe they became engaged to be married. In 1931, there was an upset to the engagement. Svetoslav was summed back to India by his father who did not want this marriage to take place. Natacha had threatened to sue Svetoslav for breach of promise. Svetoslav eventually married someone else.

In 1934, Natacha Rambova met her second husband his name was Alvaro de Urzaiz in Egypt. Alvaro was a British educated descendent of a noble Basque family from Spain. They were secretly married in a civil ceremony in Paris but in deference to the wishes of his family they were married in a Catholic ceremony at the Cathedral of San Francisco, Palma Majorca. This relationship had similarities to her previous ones. However, Natacha and her husband moved to Majorca where she had property. They lived here during the Spanish Civil War both Natacha and her second husband began a business of buying up old villas and modernizing them for tourists. This was financed from an inheritance she received from her step-father. Although there is not a lot of information about this relationship I did find out that Alvardo was on the pro-fascist side while Natacha was on the opposite side. Natacha fled to Nice, France where she suffered a heart attack at the age of 40 years. In 1939, she divorced her second husband.

In summary, Natacha Rambova was a modern woman who lived in a male chauvinistic world. Natacha lived her life on her own terms oftentimes selfish and self absorbing without regrets. However those choices that she made had some devastating effects on some people that she had relationships with.

1921 – Silent Film Actress Claire Windsor talks about her one and only date with Rudolph Valentino

Silent Film Actress Claire Windsor gave an audio interview in which, she talked about a time where she had a date with a little known actor.

The year was 1921; and both were extras in the film industry. One night, Claire Windsor and her escort had a date for dinner and dancing at a popular night spot called the Running Country Club in Los Angeles. During that time period, this was where the rich and famous liked to dine. During the course of the evening, she made eye contact with a very dreamy handsome man whose name was Rudolph Valentino. Rudolph Valentino was on the dance floor dancing with an older woman while she was dining with her dinner date and yet he continued to maintain eye contact with her throughout his dance. Rudolph asked Claire out for a date. So for their date, they travelled by street car to a hotel restaurant downtown where they had dinner and went dancing. Claire noted he was a very good dancer. Rudolph evidently did not have enough money so they walked all the way to his place where they went to see his ‘etchings’. He lived in a one room apartment where they had to walk down 4 flights of stairs to get to. He must have thought she was not ignorant of what he meant by this invitation. Once they arrived he proceeded to chased her around the apartment which ended with her crying and asking for him to take her home in which he did. To listen to this great the link is referenced below in the source

Source:

http://www.frequency.com/video/claire-windsor-interview-claires-date/114425009

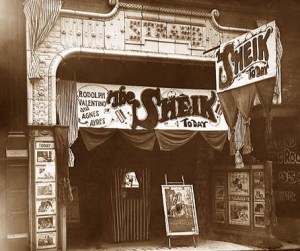

Defining the Latin Lover: Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik (1921)

Defining the Latin Lover: Rudolph Valentino in The Sheik (1921)

In Latin Lover: The Passionate South – one of the rare studies extensively dedicated to the subject— Gianni Malossi refers to a dictionary[2] in order to define the phenomenon of the Latin Lover: “passionate, but romantic, lover; it is believed, above all in Northern European countries, that they are men from Latin countries; heartbreaker, seducer” (Malossi 18-19). To provide a more elaborate, coherent definition of the phenomenon seems almost impossible as characteristics ascribed to the Latin Lover vary from his being “mute” (R. Rodriguez 107) to his ability to “use a lot of words” ( Malossi 30), from “a tendency to be short” ( Malossi 66) to his being “tall” (Limón 137), from his incarnation as “phantom, sheik or matador” (R. Rodriguez 107) to his fixed association with the cravat (Malossi 35) and the costume (Reich 35).

Opinions on the origins of the icon differ as well: whereas some consider the Latin Lover to be an archetypal figure (Thomas, 9) ranging back to Zeus (Malossi 64), Jacqueline Reich points at his historical and anthropological roots in Renaissance and Mediterranean culture (Reich 2-3). Others, such as Ramírez Berg (4), insist on his genesis in Northern conceptions of Latin otherness, which suggests an affinity with 19th-century debates on the differences between Anglo-Saxon and Latin “races” (Litvak). The one point all studies dealing with the Latin Lover have in common, however, is their abundant use of photographic materials, thereby revealing what goes almost unnoticed in the definitions: the profoundly visual nature of the stereotype. And though the pictures included show a certain disparity, limiting themselves either to actors performing roles connected to the [End Page 2] Latin Lover or expanding the notion to real-life examples such as Onassis (and even Che Guevara, to some), no disagreement exists regarding the name of the very first incarnation of the icon: Rudolph Valentino (1895-1926).[3]

This Italian immigrant to the United States, born under the name Rodolpho Guglielmi, first earned a living in the United States as a gigolo – a male dancing partner for wealthy women. However, he soon made his way to the hearts of millions of women by his dashing appearance in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), where he performed a seductive dance as an Argentinian tango-dancer.[4] The association between Latin Lovers and dance will become a fixed one in the following decades. It was The Sheik (1921) in which “he began to define a new kind of screen lover and an Other way of making screen love” (Ramírez Berg 115). In spite of the paradigmatic nature of this film, books on the Latin Lover limit themselves to brief mentions of its plot and instant success. The way in which the two terms united in the expression “Latin Lover” is inscribed in this movie has not yet been the object of more extensive commentary. This is all the more striking since, according to Ramírez Berg, this movie launched “the Latin Lover [as a] remarkably consistent screen figure, played by a number of Latin actors (…), all maintaining the erotic combination of characteristics instituted by Valentino” (115).[5]

When we take a look at this famous film, we notice that nothing in the movie – at least at first sight – sustains Rodriguez’s close association of Hispanicity and Latin Lovers: an Italian actor plays the role of the Arab sheik Ahmed (Rudolph Valentino) who falls in love with the British lady Diana Mayo (Agnes Ayres). However, the term “Latin” was used in those days in a broad sense, including all those who spoke a language derived from Latin (so also the French) and sometimes even the Greeks and all of the Mediterranean people (so also inhabitants of Arab countries).[6] In The Sheik, this broad sense of Latinness is defined by a first, major oppositional figure that establishes a difference between Northern and Southern countries as visually expressed by the two main characters: the fair-haired Anglo-Saxon young lady with the pale hands stands in opposition to the Arab sheik Ahmed with the very dark eyes. Besides this sharp contrast between North and South, there is a second one that concerns not racial features, but cultural values. On the one hand, Ahmed represents premodern patriarchal Arab values when he captures Diana during her trip through the desert in order to take her to his tent. As he explains to a friend: “When an Arab likes a woman he sees, he takes her.” On the other hand, there is a certain reticence in him because he refrains from taking Diana by force when he notices her despair at the situation she finds herself in: he has received part of his education in France and it is this European aspect in his upbringing which seems to account for a softer approach to the woman.[7] There is in fact a range of cultural differences varying from the complete Anglo-Saxon Northern values over the more mitigated European Latinity to the complete otherness of Arab Latinity. It is this “range” which grants the Sheik his erotically productive ambiguity, evoking both “suavity and sensuality, tenderness and sexual danger” (Ramírez Berg 115). In this combination, suavity and tenderness are evoked by European Latinity (France and Italy), whereas sensuality and sexual danger are projected onto the Arab world.[8]

If the tension between European and non-European Latinness, tenderness and sexual danger, is what grants the Sheik his erotic appeal throughout the movie, the film surprisingly resolves the antinomy between these opposed values in the end. The happy ending is indeed provided by a revelation concerning Ahmed’s true background: he was the [End Page 3] orphan of an English father and a Spanish mother found in the desert, after which he was adopted by an Arab sheik. This ending is doubly productive: it sanctifies the union between Ahmed and Diana as a repetition of a previous relationship between partners from the North and the South of Europe, and it clearly places Ahmed on the European side. To put it even more strongly, one could argue that Ahmed’s very ability to learn the European lessons in education and human rights is explicable by his innate European blood.[9] In a way, Ahmed is a true European, dressed up as an Arab. His clothing as a sheik is his costume. His Arab identity, his mask.

As a lover, Ahmed combines features of both forms of Latinity: he serenades Diana secretly below her window while she sleeps in the town of Biskra but he also abducts her against her will in order to possess her. He connotes softness and strength. This strength is what turns him into a dangerous man, who is able to frighten Diana and make her obey. On the other hand, it is also this capacity which turns him into her savior when she tries to escape through a desert storm, or falls into the hands of the Arab bandit Omair. Here, the sheik turns into the hero who saves the damsel in distress by plucking her from the ground and riding off with her on his horse in order to protect her.

Ahmed’s moral and physical strength functions as a token of his sexual superiority with respect to Diana as a woman. At the same time, it singles him out as “the other man” from a double perspective. First, his strength distinguishes him from the men in Diana’s own society, who appear to be too weak to control her strong character (e.g., she laughs at her brother when he tries to talk her out of her plan to travel to the desert). Second, as an Arab, he is not to be confused with other Arab men either, because he does not resort to clear violence against women, unlike the desert bandit Omair. The fact that he is neither identical with the British men – who all wear moustaches – nor the other Arabs – who all wear beards – is visually expressed by the many close-ups of his hairless face, accentuated by his turban.

Finally, the two terms under scrutiny – Latin and Lover – are of course intimately connected. What Diana is attracted by in Ahmed from the start is not only his strength, it is also his belonging to another culture: exoticism and eroticism go hand in hand. There is immediate attraction from the first time they see each other, in the town of Biskra, before Diana leaves for the desert. And when she is denied access to the Arab casino, she boldly decides to dress up as an Arab dancer, after having watched the sensuous moves of this Arab woman with fascination. She even insists on borrowing exactly the same clothes this dancer was wearing, thereby suggesting a desire to experience the Arab sensuality in person. As Said has explained, the Orient not only symbolized sexuality as such, but very often also the promise of a different kind of sexuality, generally projected onto the female body (Said 180). In The Sheik, this kind of sensuality is appropriated by Diana as she cross-dresses culturally and feels her senses aroused by the dancer. At the same time the movie performs a twist on the Orientalist discourse of its time by turning the male partner into an object of desire.

In all, the first Latin Lover can be described as a highly ambivalent figure who, in the end, reconciles the opposition between the North and the South by inscribing it into a shared feeling of Europeanness. Hispanicity here performs a syntactical gesture between North and South. In the words of Clara Rodríguez commenting upon Valentino and his imitators, “All of these stars conformed to European prototypes – perhaps to southern and eastern European prototypes, but clearly in the evolving fold of what it meant to be ‘white’ [End Page 4] (and upper class) in the United States at the time.” (C. Rodríguez 28) Latinness is therefore on the one hand the suggestion of Otherness, but at the same time based on the reassuring recognition that this Otherness is within the limits of the own identity.

Valentino’s appearances in movies such as The Sheik set in motion the so-called “Latin craze” (C. Rodríguez 28) that flourished in the Roaring Twenties. This period was characterized by major social changes brought about by World War I and the Russian Revolution, and economically beneficial to the United States until the Depression broke out. The social changes altered the position of woman and to some also implied “libertad en el amor” (Belluscio 13). Belluscio considers the Latin Lover as an expression of modernity as it manifested itself around 1900: “En esa zona del planeta [USA], los hábitos se modificaban con el automóvil, la radio en casa, la publicidad impresa, y las salas de cine simbolizaban el nuevo urbanismo yanqui. La difusión e influencia del séptimo arte creó una idolatría sin fronteras, engendrando psicosis colectivas (…) En ese momento singular, que ambulaba entre la añoranza y el futuro, el ‘latin lover’, macerado como una burbuja, surgía excitante, digno de la ostentación, el lujo y el donaire del ‘American way of life’” (13-14). At the same time, both Ahmed and Diana belong to the upper classes of their society, which might reflect the nostalgia for a vanishing aristocracy in that same period (13). This is also why other authors connect the Latin Lover to the expression of anti-modern values (Malossi 24; Reich 26). In a sense, he is both a symptom of modernity and a reaction to it. Once again, he turns out to be an ambivalent sign.

Source:

“In January 193…

“In January 1936, on my first trip to Egypt, I felt as if I had at last returned home. The first few days I was there I couldn’t stop the tears streaming from my eyes. It was not sadness, but some emotional impact from the past- a returning to a place once loved after too long a time.”–Natacha Rambova

16 Aug 1925 – Rudolph Valentino Joins UA

Rudolph Valentino has deserted all his former “loves” as far as producing pictures is concerned, and is now in close association with United Artists. His first picture under their flag is “The Hooded Falcon,” a colorful Moor- ish drama.

1922- Costume Designer for “The Young Rajah”

This blog already contains a post about Natacha Rambova as the wife of Rudolph Valentino. This one is about Natacha Rambova the costume designer.

In 1917, Natacha Rambova, started her brief career as a Hollywood costume and set designer for Cecil B. De Mille. Between 1917 and 1921, Rambova made four films for Cecil B. De Mille. As a set designer, Rambova’s works were a highly stylized version of Art Nouveau, infused with the minimalistic feel of Art Deco. She enjoyed employing the flower motifs and the circular ornamentation of Nouveau in all her designs. Her costume designs were bold, feminine and had a European flair that many Hollywood fashions at the time lacked, no doubt as a result of the complete artistic control she exercised over her work. For her costume work on The Young Rajah Natacha traveled to New York to work on the costumes. The film is perhaps best remembered today for its elaborate and suggestive costumes, which were designed by Valentino’s wife Natacha Rambova. Photographs of Valentino wearing these outfits, some of which left little to the imagination, are still widely circulated today.

“There are many…

“There are many roads — all lead to God”.–Amos Judd, “The Young Rajah”

1922 Phil Rosen, Director “The Young Rajah”

Lets now take a look at the director of Rudolph Valentino’s silent film “The Young Rajah”. Phil Rosen was born on 8 May 1888 and started out as a cinematographer for Thomas Edison. Rosen worked as a projectionist and lab technician before becoming an $18-a-week cinematographer in 1912. In 1918, he went to Los Angeles. During his career he directed 142 films between 1915 and 1949. Although he was never a actor like so many others he never truly enjoyed the success in talkies like he did with Silent Films.

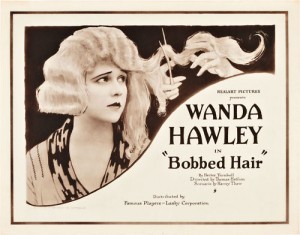

“Cute, sassy, a…

“Cute, sassy, and can even ride a horse Wanda Hawley was one of my favorite actresses to work with.”–Tom Mix, Silent Film Star on his co-star Wanda Hawley

1895-1963 Wanda Hawley Co-Star “The Young Rajah”

To wrap up our week, Wanda Hawley was a co-star of the movie “The Young Rajah” that starred Rudolph Valentino. But what do we really know about her? Wanda was born on 30 Jul 1895, in Scranton, PA. Her real name was Selma Wanda Pittach. Athough it is noted in Photoplay Magazine, circa 1918, her name was changed to Wanda Hawley. Wanda was a classically trained Opera Singer but found that acting paid better and felt that was more of her calling. It is claimed by Paramount Pictures Publicity Department that she was discovered by Cecil B. Demille. Wanda Hawley began her screen career years before meeting DeMille, and had appeared under the screen name Wanda Petit opposite both Tom Mix and William S. Hart, and played Douglas Fairbanks Jr.’s love interest in “Mr. Fix-It” in 1918. But DeMille made her a star in “Affairs of Anatol,” with Wallace Reid and Gloria (“I’m ready for my closeup, Mr. DeMille”) Swanson in 1921. It is noted, her best years were when she was under contract to Paramount Studios.

At the height of her career she received the same amount of mail as Gloria Swanson another famous silent film star who was Rudolph Valentino’s co-star in “Beyond the Rocks” She never made the transition to talking pictures. Falling on hard times, she reportedly worked as a call-girl in San Francisco during the Great Depression years of the early 1930s. She died in 1963 and is buried at Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

Feb 1923 Motion Picture Magazine – The Young Rajah starring Rudolph Valentino

Rodolph Valentino also came to the screen again this month. After witnessing “The Young Rajah,” in which he is starred, we begin to understand many things, principally among them why Mr. Valentino desired to select his own casts.And if it wasn’t that we remembered from our nursery days that “Two wrongs do not make a right,” we would be sorely tempted to applaud Rodolph Valentino for refusing to continue with his contract. At any rate, while we may still disapprove of him ethically, we sympathize with him emotionally. All of which has probably led you to believe that this is a pretty bad picture. It is. It is about as artistic and as satisfying as a cheap serial. As a matter of fact, it is the concentrated essence of those things which have composed serials since time immemorial. “The Young Rajah” is based on the novel, Amos Judd. It tells of Amos who has been reared in a provincial American town. Then there is the Far East with its rajahs and its maharajahs. Amos really belongs to the East. Furthermore, he belongs to a line of its rulers, and he has inherited the sixth sense bestowed by one of the Indian gods upon the sons of this noble family. It is this sixth sense which serves him well when the usurpers of this kingdom learn of his existence in America and threaten his life. Even The Valentino is somewhat submerged in the mediocrity of this production. Of the supporting cast Charles Ogle is the one member who stands forth with any degree of effectiveness

12 Nov 1922 – Young Rajah Screen Credits

This movie was based on a play/novel “Amos Judd” by John Ames Mitchell Directed by: Phil Rosen

Written by: June Mathis – screenplay

~Cast~

Rudolph Valentino … Amos Judd

Charles Ogle … Joshua Judd

Fanny Midgley … Sarah Judd

George Periolat … General Devi Das Gadi

George Field … Prince Rajanya Paikparra Munsingh

Bertram Grassby … Maharajah Ali Kahn

Josef Swickard … Narada – the Mystic

William Boyd … Stephen Van Kovert

Robert Ober … Horace Bennett

Jack Giddings … Austin Slade Jr.

Wanda Hawley … Molly Cabot

Edward Jobson … John Cabot

Farrell MacDonald … Amhad Beg – Prime Minister

Spottiswoode Aitken … Caleb (uncredited)

Joseph Harrington … Dr. Fettiplace (uncredited)

Julanne Johnston … Dancing Girl (uncredited)

Pat Moore … Amos as a Child (uncredited)

Maude Wayne … Miss Elsie Van Kovert (uncredited)

~Remaining Credits~

Production Company: Famous Players-Lasky Corporation

Released by: Paramount Pictures

Cinematography by: James Van Trees

Costumes by: Natacha Rambova

Presenter: Jesse L. Lasky

1909-1918 – Ames Mitchell, Author of Young Rajah

On April 13, 1909 The Times reported that Ames Mitchell had bought a “four-story dwelling at 41st East, 67th Street, New York City.” It was a time when the old brownstones had fallen out of fashion. Architects Denby & Nute instead stripped off the old façade and transformed the house to a five-story neo-Classical beauty. Mitchell had been educated as an architect at Harvard and later at the Ecole National Superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. But he was a man of many more talents. In 1883 he co-founded the humor magazine Life, the position for which he would be best remembered. He was also an artist, illustrator and author. Mitchell and his highly-popular magazine would introduce America to several new writers and artists—among them Charles Dana Gibson (famous for his Gibson Girls). He found the time to write over a dozen novels, one of which, “Amos Judd,” became the 1922 silent film The Young Rajah starring matinee idol Rudolph Valentino. The publisher-novelist-architect also spent time at the easel and several of his etchings were given honorable mention in the Paris Salon. He and his wife spent the summers in their country home in Ridgefield, Connecticut. Mitchell established the Life Fresh Air Camp in Branchville, which brought city kids to the country for many years. It was located where Branchville School is now. It was there, on June 29, 1918 he died. The New-York Tribune reported that “He suffered a stroke of apoplexy early in the day and his death followed a few hours later.” Mitchell was especially generous to his household staff in his will. His chauffeur received the same amount as did his own sister–$5,000 (about $50,000 today)—and the “servants in his employ all receive legacies of $500,” reported The Sun.

1 Jul 1922, Work on “Young Rajah” Started.

Philip E. Rosen and his megaphone rang the gong on Rudolph Valentino’s second Paramount starring production, “The Young Rajah.” June Mathis wrote the script from “Amos Judd” the novel by John Ames Mitchell. “The Young Rajah” is divided into two complete sequences, one East Indian and the other New England, each requiring an individual set of players. Hence, the supporting line-up is a long one, as well as a notable one. Wanda Hawley is the leading woman, with little Pat Moore, Bertram Grassby, Maud Wayne, J. Farrell McDonald, Bill Boyd, George Periolat, George Fields, G-wge Ober, Charles Ogle, Florence Hidglcy and Edward Jobson among those already signed.

“Men should be …

“Men should be judged not by the tint of their skin. The gods they serve, the vintage that they drink Nor by the way they fight, or love, or sin. But rather by the quality of thought they think.” -Intertitle from The Young Rajah, Paramount, 1922.

“(Valentino was…

“(Valentino was) what is commonly called for want of a better name, a gentleman. In brief, Valentino`s agony was the agony of a man of relatively civilized feelings thrown into a situation of intolerable vulgarity.” – H.L. Mencken

1921 – Patsy Ruth Miller A former co-star of Rudolph Valentino’s

Patsy Ruth Miller (January 17, 1904 – July 16, 1995) was an American film actress who was discovered by the actress Alla Nazimova at a Hollywood party, Patsy Ruth Miller got her first break with a small role in Camille, which starred Rudolph Valentino. Miller’s first billed part was in Alla Nazimova’s “Camille” (1921). Prior to beginning work on the movie, she became close friends with Nazimova and spent quite a bit of time at her house. Valentino, prior to his sudden rise to stardom, was also to be in the picture and spent quite a bit of time there, too. Miller and Valentino spent many hours in Nazimova’s pool swimming, but nothing romantic ever developed between the two of them. Miller was 17, and Valentino was 26.

“One evening when Nazimova was entertaining for dinner, Valentino, Miller and several other guests were there. According to Miller, Valentino began a story that told “something about a ballerina, something about being left waiting at the boat. . .” However, before Valentino progressed very far into the story, Nazimova spoke to him in Italian. Valentino said, “Oh, scusi,” and the story came to an abrupt end. Miller felt the story had been halted due to her young age, and she protested to Nazimova but to no avail. Sometime after World War II, Miller said she assisted in carrying foodstuffs to Scotland where there was still a shortage of many food items. She was invited to tea by a friend, and they were served by the maid, “a gaunt, middle-aged woman who looked more Slavic than Scottish. . .”At one point when the maid left the room, the hostess asked Miller if she remembered a cinema star named Valentino. Without revealing her personal contact with Valentino in those early years, Miller simply replied, “Yes.” “Well,”the hostess said, “she knew him personally,” referring to the maid. When the hostess left the house for her weekly ration of gasoline, Miller said she commented to the somewhat unfriendly maid, “I understand you knew Rudolph Valentino.” At first, when Miller said she knew him, too, the maid appeared uninterested. However, Miller added that she had appeared in a movie with him once. At that point, the maid’s demeanor changed. She became more friendly toward Miller and confessed she had known Valentino once, too. When Miller asked the maid to tell her about it, she began her story. She was Polish, she said, and a great ballerina before the First World War. She studied in Russia and danced before many of the crowned heads of Europe. One of her admirers was a German prince for whom she became somewhat of a spy sending him information as she traveled the continent. When in Milano, Italy, she said she unexpectedly fell in love with a young student who was much younger than her. Although she was being unfaithful to her German Prince, although the affair had become a scandal, and although his family was terribly upset, she said they could not help their love. When she left Italy, the young man followed her. For six months they were together during which time she taught him to dance, very easily, by the way, since he was so talented. While in Paris, she received word from her German Prince that the French knew of her spying. She decided the safest place for her would be in America, so she obtained the necessary papers and sent her young lover on ahead to make sure all arrangements were made for their trip. Suddenly, all of her plans fell through. The police came and took her papers and passport away. It was only through the help of a former lover that she was able to escape to Spain. She had no way of contacting her young lover, and she said she somehow knew that he would go on to America without her and not miss this chance. During the war she had to sell all her valuables, but, nevertheless, she did survive with the help of an admiring Spaniard. Seven years later, the maid said, she saw her young lover on the screen and knew he had met with success. She said she never made any attempt to contact him”..

Reference:

My Hollywood, When Both Of Us Were Young, The Memories of Patsy Ruth Miller by Patsy Ruth Miller, O’Raghailligh Ltd., 1988

Natacha herself…

“She would see to it that she never had children”..Natacha Rambova, former wife of Rudolph Valentino

“With butlers, …

“With butlers, maids and the rest, what work is there for a housewife? I won’t be a parasite. I won’t sit home and twiddle my fingers, waiting for a husband who goes on the lot at five a.m. and gets home at midnight and receives mail from girls in Oshkosh and Kalamazoo” –Natacha Rambova, former wife of Rudolph Valentino on her breakup with Valentino

1924 – Rudolph Valentino Sports a Beard

In the 1920’s, Rudolph Valentino was considered fashion forward. What he wore others would emulate him. This blog post is going to discuss the time when Rudolph Valentino sports a beard. In 1924, a new company called Ritz Carlton was formed to produce the next Valentino film. This unmade Valentino film would have been based off the story of El Cid. Set in 14th Century Spanish Court, Valentino would play a Moorish Nobleman and Warrior who falls in love with a Moorish Princess (most likely Nita Naldi). Having the right to select his own story, Valentino decided to make ‘The Hooded Falcon’. The script was written by Natacha Rambova. So Rudolph and Natacha went on a trip to Spain to purchase props, costumes and conduct extensive research for this movie. While in Spain, Rudolph grew a beard. In November the couple arrived back in New York to face a barrage of photographers and fans. Valentino was still wearing the beard he had grown in Spain. Rudolph Valentino’s beard caused such a sensation and the following announcement was to be issued by the Associated Master Barbers: ‘Our members are pledged not to attend a showing of Rudolph Valentino’s photoplays as long as he remains bewhiskered”. The male population is very likely to be guided by the famous actor to the extent of making beards fashionable again and such a fashion would not only work harmful injury to Barbers but would so utterly deface America as to make American citizens difficult to distinguish from Russians’. The threat by the Association of Master Barbers strike against Valentino’s films seems extreme.

“When asked why…

“When asked why she married Valentino, she replied, “It was simply a case of California, the glamour of the Southern moonlight and the fascinating love-making of the man.”–Jean Acker, Former Wife of Rudolph Valentino

1897-1966 Natacha Rambova, Rudolph Valentino’s Second Wife

This blog owner has been fascinated for years with the woman named Natacha Rambova who lived her life on her own terms. There will be many more posts on her as we continue the journey of “All About Rudolph Valentino.

Natacha Rambova lived in a time where women were still suppressed and misunderstood. Unless you personally knew her how could you possible understand what made her think or feel? The Internet has a lot of other websites and blogs about both her and her former husband Rudolph Valentino with some written in glowing terms about him and a lot in not so glowing terms about her. In 1991, Mr Michael Morris wrote a wonderful book about Natacha called “Madame Valentino”. For those that are reading this post and have not read his book, I would highly recommend doing so in order to have an understanding of the complexity that makes up this fascinating woman. Natacha Rambova a highly educated woman was first and foremost an artist who explored every artistic venue made available. This exploration was achieved through the study of ballet, costume design, mythology, contemporary culture, etc. As an artist Natacha wanted others to understand and appreciate the beauty of design whether it was as a costume or a set designer. Natacha was a perfectionist in everything she produced and the results were nothing less than fantastic. Art Deco and Oriental were the major factors in her designs and what she wore.

Although the 1920’s were considered a time where it was off with the old and on with the new modern ways and thinking. This was not necessarily true in everything. Women were still fighting for their rights and freedom they were still very much in the background. For someone like Natacha Rambova with her demanding personality and strong opinions this worked for her and against her. This was especially the case in her personal life, where her husband Rudolph Valentino was very much a traditionalist who liked nothing better than to come home from a hard day at the studio to be greeted by his wife and children and a home cooked meal. Natacha Rambova was a career woman who did not want a traditional role in a man’s life but one of an equal role. This is why I wrote earlier about her being born in the wrong time.

Natacha never achieved any sense of personal fulfillment in her personal life. But her professional life was one of achievement and influence which was achieved in various ways. One of them was a patent she received in 1926 through her design for a doll and matching coverlet, clothing designer, artist, researcher and writer on Islamic Art. Natacha was a very private person who did not feel comfortable sharing her world with others. While the rest of us may never understand what made her think and feel she was still a force to be reckoned with and you cannot deny the legacy she left for others to explore.

1922-1924 June Mathis and Ben-Hur

Little has been written about June Mathis, a successful screenwriter and production executive from 1915-1927. Mathis began her professional career in 1901 at the age of fourteen by going on the vaudeville originally a light song, derived from the drinking and love songs formerly attributed to Olivier Basselin and called Vau, or Vaux, de Vire. stage in San Francisco. By 1915, she had performed with a number of companies all over the country. Her most notable stint was with Julian Eltinge. After appearing in the Boston Cadets Revue at the age of ten in feminine garb, Eltinge garnered notice from other producers , the leading female impersonator of the times, and for whom Mathis spent four years as lead ingénue. After her stage career, Mathis turned to screenwriting. By 1918, she was the primary writer for Metro Studios, turning out scripts for their major stars such as Alla Nazimova, Francis X. Bushman, Beverly Bayne, and Viola Dana (Letter from Metro–1919). When Metro moved to Los Angeles. in 1919, so did Mathis–as head of their scenario department. Her first project, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse allegorical figures in the Book of Revelation in the Bible. The rider on the white horse has many interpretations—one is that he represents Christ; the rider on the red horse is (1921), would establish her status in the movie industry for the rest of her career (“June Mathis Confers”). Not only did Mathis write the script, but she staked her future on casting the little-known Rudolph Valentino in the lead. For the rest of their short lives, Mathis and Valentino were closely linked, both personally and professionally. She also selected Rex Ingram to direct (Ramsaye 799). In 1922 Mathis joined Goldwyn Studios and immediately gained responsibility for guiding to completion the highly anticipated motion picture version of Ben-Hur. The following year, she became general manager in charge of production. Her responsibilities included approving scripts; assigning the studio’s directors (e.g., King Vidor, Tod Browning, Marshall Nielan, and Victor Sjostrom) to projects; overseeing several productions, most prominently Erich von Stroheim’s Greed; and writing and contributing to several other scripts. But, during this time, her main responsibility, which also drew the most attention from the press and the public, was Ben-Hur. (2) From 1922 to 1924, besides working on the script, Mathis was also in charge of selecting the director and cast, and ordering the costumes, wigs, and beards. When the production subsequently fell apart and her script was rejected, an entirely new team assembled by the newly formed Metro-Goldwyn Studios completed the film. So why consider a rejected script? Mathis’s screenplay and her correspondence related to Ben-Hur demonstrate how the screenplay was part of a pattern of how she redefined masculinity and gender roles in relation to World War I, a pattern that began during the war years and continued through her scripts for Valentino. Latin; see example.] of how a highly successful woman executive’s ideas were dismissed and how she was brought low in part due to the politics to which Leab alluded. With the closing of her production and little attention to her scripts, her vision has been lost. I hope to recover that vision by examining well-established critical attitudes towards screenwriters and melodrama, and then explain Mathis’s ideas by analyzing how her script for Ben-Hur built on the spirituality inherent in the tale’s use of the Jesus story to more clearly assert the importance of spiritual values (Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and mystical) and art (especially that of the cinema) over the futility of Militarism

FROM NOVEL TO STAGE TO SCREEN