Posts Tagged With: Rudolph Valentino

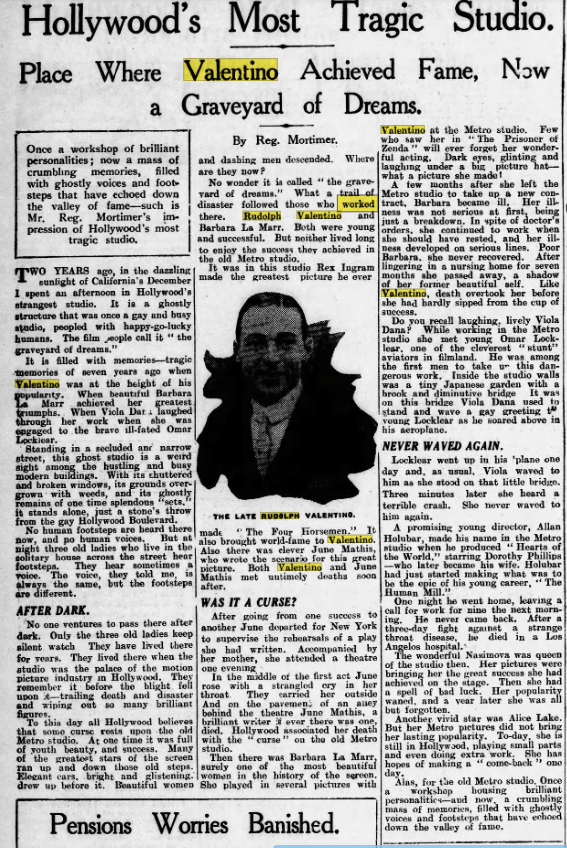

1996 – Shear Destiny: Yvonne Sapia’s Valentino’s Hair

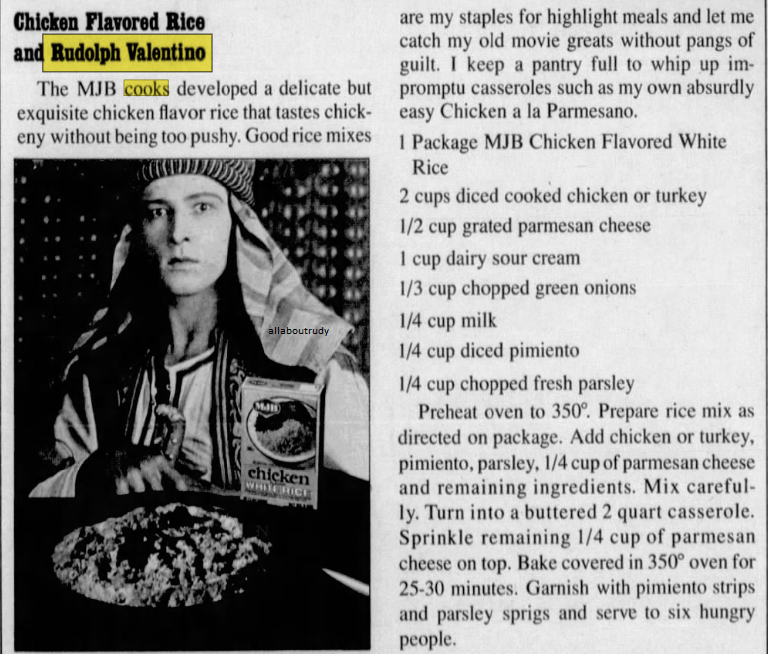

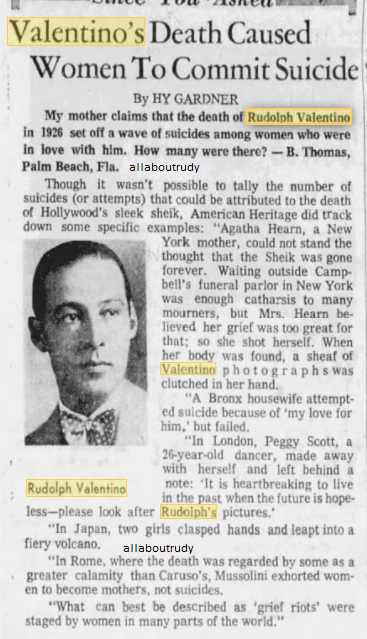

In 1926, a young Puerto Rican barber named Facundo Nieves is summoned by an exclusive Manhattan hotel to cut the hair of Rudolph Valentino, touching off a chain of tragic and compassionate events that comprise Yvonne Sapia’s imaginative first novel, Valentino’s Hair. Sapia creates a novel that is noteworthy for its creative narrative structure, its use of historical context, and its resonant motifs that allow the author to explore the consequences of forbidden love in a xenophobic and racist United States. This essay is a modest at- tempt to identify and discuss the implications of the issues that Sapia raises, as well as to examine the narrative structure and historical context within which she places them and the motifs which serve to illuminate them. More specifically, I will argue that Sapia’s use of his- torical materials and motifs enables her to move beyond the telling of a modern fairy tale with a familiar theme (the abuse of a magical talisman) toward an effective critique of race relations during a specific period of U.S. history. Paradoxically, her lack of attention to interracial issues during a subsequent period of U.S. history, also depicted in the novel, calls into question the novel’s optimistic resolution. The novel is composed of two interwoven narrative strands. The first is Facundo Nieves’s dying confession to his son Lupe of how he cut Valentino’s hair and later used the clippings to create a powerful aphrodisiac that ultimately proved fatal to the young woman he seduced. Sapia skillfully parcels out this story, interspersing it with the second, longer narrative which details Lupe’s coming of age, so that the reader does not learn until the penultimate chapter that this first- person narrative is Facundo’s dying confession. If the reader will bear with me, it is necessary at this point to summarize briefly the key events of Facundo’s story. It is 1926, Facundo Nieves operates a small barbershop in a first- class Manhattan hotel where one hot, summer day he is called by the front desk to give one of the guests a haircut. Upon his arrival at the hotel room, Nieves is stunned to find that his customer is Rudolph Valentino, one of his movie idols. As Nieves cuts the star’s hair, Valentino confides in the barber and tells him, “You do not realize it, but you are cutting away at my life too, time leaving me like mo- ments falling to the floor”. When the haircut is finished, Valenti- no gives him a hundred dollar bill, compliments his work and departs, while Nieves, “like a madman,” gathers up the clippings of Valentino’s hair. A few weeks later, Valentino collapses, is hospitalized and under- goes surgery for an unnamed illness. His condition worsens and Nieves is drawn by some instinct to the hospital where he is allowed to shave Valentino, whose last words to the barber are “cuida el pelo,” take care of the hair. The next day Valentino is dead and Nieves, un- nerved by the star’s final words to him, consults one of the local bru- jas (literally a witch, but more properly a sort of folk healer). The bruja tells Facundo that the hair is “the most powerful aphrodisiac” she has ever seen and she instructs him in its use, but warns him that it also has the potential to be misused. Facundo then learns the whereabouts of Valentino’s body and is given a pass admitting him to a private viewing later in the day. As word of Valentino’s death spreads, an unruly crowd gathers outside the funeral home and it is in this chaos that Nieves bumps into the young white woman he has long desired but who has consistently rebuffed his attentions. As they gaze upon Valentino’s body, Facundo whispers to her that he has some of Valentino’s hair and she accompanies him back to the barbershop where Nieves allows her to see and touch the hair. Suddenly she swoons and Nieves revives her with some rum into which he has mixed the aphrodisiac made from his blood and Valentino’s hair, a potion of which he also partakes. The effects are immediate and dramatic. As they make love in the barber chair, the woman calls out Valentino’s name and appears to lose consciousness a second time, even as Nieves continues to make love to her. Suddenly, he realizes that she is dead, that he has killed her and, in the novel’s most disturbing scene, Nieves still under the spell of the aphrodisiac-penetrates the woman a third time. As the effect of the aphrodisiac wears off, the horrible enormity of his actions settles upon Nieves. He slashes at his legs with a razor, becomes violently ill and loses consciousness. When he comes to, he manages to call his friend Mangual, who convinces the barber that his role in the woman’s death must be covered up. With the help of two Puerto Rican nationals, the dead woman is smuggled out of the hotel and her death made to appear the suicide of a woman dis- traught over the death of Valentino. The ruse is successful; foul play is not suspected and Nieves is never implicated in her death. Thus, ends the narrative timeline of 1926, all of which Nieves confesses his son Lupe on his deathbed in 1960. The second major storyline, told in the third person, relates coming of age in 1950s New York, as he learns about life’s hardships and ultimately is forced to reassess his father and the legacy bestowed upon Lupe. Through his eyes we see portraits of different family and community members and learn something of their gle and suffering, as well as the elements that bond them together. this sense, Sapia uses Lupe as a camera lens through which she ates snapshots of his extended family, creating of the novel a family album of the Puerto Rican community in The Bronx. This narrative structure, alternating between two prominent ries and two distinct voices, allows Sapia to achieve certain effects well as to explore different themes. Facundo’s dying confession which is disrupted by the story of Lupe’s coming of age-is used generate suspense and drive the narrative: the reader is anxious know what Facundo will do with the hair. But the confession is also used to focus attention on particular themes: issues of social power, responsibility, and the consequences of abusing such power. Lupe’s coming of age, on the other hand, allows Sapia to portray a commu- nity of people as seen through the eyes of one of its members who is learning how to function within it. There is also a third, less promi- nent narrative voice, most clearly visible in the chapter “Mythology of Hair,” that is scholarly, detached and almost clinical, and moves from scientific authority to mythological authority. Here, Sapia discusses common beliefs in the supernatural power of hair, one in stance of the magic and folklore that appear throughout the book and are shared beliefs in the Puerto Rican community. One of the myths discussed in this chapter is the idea that hair contains an individual’s essence and that the cutting of hair robs a person of some of his or her strength and vitality, as in the biblical story of Samson and Delilah which Sapia mentions. As she writes in the novel, “Said to have magical powers, its removal disturbs the spirit of the head, the soul of the body. The notion is universal that a person may be bewitched by means of clippings of hair”. This is precisely the notion that Sapia dramatizes in her novel in order to comment upon the very human need to possess what one desires, an attitude facilitated by the hedonism characteristic of the Jazz Age. The story of Valentino and Facundo’s use of his hair is very much linked to the historical time frame of those events. In many ways, Facundo’s actions, Valentino’s actions, and Valentino himself mirror the era. From the very outset of the novel, Sapia is careful to emphasize the 1920s as a distinct historical period: “In 1926, I was young, and I was a part of a world filled with such life, a world which was eating at its own edges without being satisfied. The Roaring Twenties they didn’t roar, Lupe. They swelled with passions. They danced, and I danced with them”. Facundo’s words here, as he begins his confession to Lupe, are ironic, for by the time the read- er reaches the conclusion of his story, she will have witnessed the dance of the 1920s, become a mob scene foreshadowing the violence of the decade to follow and like the insatiable appetite that Facundo attributes to the decade, he too will be driven by a passion he cannot control nor satisfy, as he causes a woman’s death and engages in necrophilia. Facundo’s characterization of the Roaring Twenties is just one ex- ample of how the first chapter of the novel is a crucial touchstone for the remainder of the text. Many of the events described in the opening chapter will be repeated in perverse fashion or with ironic intent later in the book and it is this doubling that gives the novel its resonance. Sapia foreshadows and underscores the importance of the rep- etition of events by means of an insistent mirror motif which she introduces almost immediately, following Facundo’s description of the 1920’s, on the narrative’s first page: “There were four large oval mirrors in the barbershop, two on one wall, two on the opposite wall. always thought they stared at each other like distant lovers, never permitted to kiss, only allowed to long for each other with their cool but secretive stares”. Not only do the mirrors placed directly across from one another so that an image caught between them replicated infinitely-suggest the duplication of events to follow as well as a doubling of desire (after luring the young woman to the barbershop and seeing her reflection in the mirror, Facundo will comment, “Now I had two of her”, their description here as “distant lovers, never permitted to kiss,” strikes the first note of the theme of forbidden love which motivates the barber’s actions later in the book, including both his decision to seduce the woman and his resolve to cover up the circumstances of her death. Mirrors are also used in the novel as a familiar device to suggest another persona latent in the viewer or as a sort of oracle that reveals the true self in a world and era obsessed with appearances. For example, as Facundo rides the elevator up to Valentino’s hotel room he glimpses his reflection in a small mirror and is surprised by what he sees: “And for that moment I thought I saw someone else. Someone who was walking towards me from another place we held in common”. And, significantly, Facundo’s first glimpse of Valentino is in a mirror with the star’s reflection alongside his own, suggesting a union of sorts and foreshadowing the ways in which Facundo’s destiny will become linked to Valentino’s. In Valentino’s case, mirror is used to suggest the disjuncture between his private self his public persona. As Facundo prepares to cut his hair, Valentino asks him to help with the man in the mirror and Facundo describes Valentino as staring “directly into the eyes of the pitiful man thought he saw in the mirror”. He continues, “I began to and disguise that perfect face, slowly, with compliance, like an complice to the development of the belief in one god” two lines suggest the extent to which Valentino’s carefully fabricated image governed every moment of his life. As Gaylyn Studlar has ed, accounts of Valentino’s early life were rewritten numerous by Hollywood publicity agents in repeated attempts to sustain popularity. In the following passage, we can see that Facundo nothing about any ideas or feelings that do not coincide with Valentino created through filmic discourse and, in fact, he will what he can to sustain that persona. He characterizes Valentino “a man who was a great lover, not a great philosopher. I didn’t to hear philosophy. I wanted to know about the desert at night, ride of the four horsemen, the posture of the tango”. Would too far-fetched at this point to suggest that Facundo’s fascination with Valentino is not unlike the mood of the public during 1920s-xenophobic and hedonistic, wishing to immerse itself in tasy in order to forget the horrors of World War I and ignore creasing unrest in postwar Europe? As noted above, Sapia’s novel contains many significant events that are “mirrored” or replicated at other chronological moments the narrative. One of the most interesting is related to Facundo Valentino at their first encounter. While the young barber cuts hair, Valentino tells Facundo of a bizarre incident that occurred hotel in California: an elderly woman sent to give him a manicure dropped dead just from looking upon him; Valentino had unleashed a sexual power that he couldn’t control. And although Valentino’s role in the death is covered up with the co-operation of the management and he is never publicly implicated, he must continue to live with the knowledge that he caused the woman’s death. do’s reaction is recounted years later to his son: Lupe, I was suddenly caught between laughing and crying. The poor man had a power he couldn’t control, and here I was absolving him his sin, listening to his confession like a priest in my white smock. now he was to do penance, he was to give something up to me. would raise my chalice of shaving cream and lift my silver razor to light and strip away Facundo’s reaction is revealing on a number of levels. First, sumes a position of power, likening himself to a priest hearing fession in a sort of spiritual transaction that sanctions his something from the penitent. This is a clever way of rationalizing later actions, the taking of the hair and the fashioning of the clippings into a love potion. Secondly, it foreshadows the later scene at the pital in which Nieves will again feel himself placed by Valentino the position of a priest administering a sacrament, this time the rites. But most importantly, Valentino’s confession to Facundo repeated by Facundo and Lupe, just as Nieves, like Valentino, find himself unleashing a sexual power he cannot control, resulting in a woman’s death. And, as in the first episode, the involvement the man responsible for the death will again be covered up, an which will torment him until he is able to confess. Like the mirrors in the book, the profession of the barber takes on many meanings and is crucial to Facundo’s sense of self and to the decisions he makes. The barber, with his razor so close to the skin, cannot afford a careless moment. However, when the barber does his job well, he becomes a type of physician or healer, making his patient feel better: “I was a kind of doctor. What I did helped people ride a stream to slow recovery, to arrive on the shore of something new, something which was hidden from sight. A secret place. A secret person”. Notice that again, we have a duality characteristic of Sapia’s narrative technique: if the mirrors are represented as devices which may reveal that dark side which is hidden within all of us, Facundo’s comments suggest that the barber’s ministrations bring to the surface that which is good but hidden within the individual. But if the barber is a kind of physician, he is also a kind of priest. Like a priest, Facundo listens to the confessions of his clients and grants them absolution. As already noted, Valentino confesses to Facundo twice. Moreover, the doctor and priest roles are combined when Facundo visits Valentino at the hospital. He is mistaken for a doctor and allowed admittance to Valentino’s room, where the dying movie star asks him for a shave that they both sense will be his last. Facundo is frightened and, in a comment that prefigures the macabre events to follow, recalls, “I had never shaved a dead man [before]”. The barber has become doctor, priest and mortician, and al- though the experience initially frightens Nieves, over time it gives him a sense of power and privilege that emboldens him to use Valentino’s hair for his own ends: I was the man who cut Valentino’s hair and learned of its power. I was the man who had shaved Valentino in his last hours. I knew him in a way no one else on that street knew him. And Valentino had trusted me with the last hours of his life. When the end came for him, he alone except for his three doctors and two nurses. He had lost con- sciousness sometime after I saw him, and the doctors had called in priest to give him the last rites. He was a priest from Valentino’s little town in Italy. Yet the truth is he had already received his last rites; had received the rites from me. Finally, the barbering metaphor establishes a tension that Sapia exploit: barbering is extremely pleasurable and sensual yet it potentially harmful if not done properly: these two extremes are arated only by the edge of a razor, and that boundary is crossed tragic ending to the novel which takes place, not coincidentally, barbershop. Facundo’s fantasy encounter suddenly becomes grotesque episode of necrophilia and self-mutilation. In her essay “Pleasure, Ambivalence, Identification: Valentino Female Spectatorship,” Miriam Hansen has noted that Valentino often viewed by biographers and cultural critics as embodying ongoing crisis of American cultural and social values” triggered World War 1. In particular, Hansen emphasizes the crisis gender relations in the United States that arose as large numbers women entered the work force and as they became increasingly portant players in a consumer economy. Thus, Hansen continues, Valentino emerges within the fractured cultural terrain created struggle between “traditional patriarchal ideology on the one and the recognition of female experience, needs and fantasies other, albeit for purposes of immediate commercial exploitation eventual containment”. Not only does Valentino, in a sense, into being as a cultural phenomenon because of these contradictory forces, but he comes to embody them or rather embody their product (the change in gender relations) to such a degree that he becomes flashpoint for opposing sides on that issue. Few popular icons polarized the men and women comprising white society to the that Valentino did. With a consistency that is nothing less than ishing, Valentino aroused contempt from men, while women whelmingly adored him. Studlar cites the notorious Chicago Tribune editorial (the so-called Pink Powder Puff attack) published month prior to Valentino’s death as emblematic of the “vitriolic mensions” of the male discourse on Valentino in the 1920s. Do women like the type of “man” who pats pink powder on his face a public washroom and arranges his coiffure in a public elevator?…a strange social phenomenon and one that is running its course not only here in America but in Europe as well. Chicago powder puffs; London has its dancing men and Paris its gigolos. with Decatur; up with Elinor Glyn. Hollywood is the national school of masculinity. Rudy, the beautiful gardener’s boy, is the prototype the American male. Hell’s bells and if the editorial and its subsequent notoriety suggest the to which American men believed Valentino represented a dangerous erosion of traditional ideals of masculinity and subsequent male power, the riots by distraught fans at his New York funeral, mostly women, as well as the scorn with which the New York Times ported their mourning, gives an even more dramatic sense of vision between male and female responses to Valentino in post-America. In order to understand this polarized, reaction to Valentino, it is useful to recall, as Hansen does, predominance of sadomasochistic scenarios in Valentino which the star is dominated by other men and women as often dominates the female love interest in the film’s narrative. Hansen also notes the “systematic feminization of his persona” through the use of exotic costumes and mise-en-scene, as well as by casting him within the film’s narrative as a performer. The outward response of a male audience to these conventions is probably not surprising. As Hansen remarks, “The vulnerability Valentino displays in his films, the traces of feminine masochism in his persona, may partly account for the threat he posed to prevalent standards of masculinity”. Conversely, Hansen speculates that: However complicit and recuperable in the long run, the Valentino films articulated the possibility of female desire outside of mother- hood and family, absolving it from Victorian double standards; instead they offered a morality of passion, an ideal of erotic reciprocity. In focusing pleasure on a male protagonist of ambiguous and deviant identity, he appealed to those who most strongly felt the effects-free- dom as well as frustration-of transition and liminality, the precari- ousness of a social mobility predicated on consumerist ideology. But the case of Valentino as cultural marker is of course more complicated than mere sexual politics; there is also his ethnicity or “racial difference” to consider. Hollywood dealt with Valentino’s otherness in filmic texts by consistently casting him in exotic, costumed dramas which, as already noted, exacerbated the perception among white American men that he was effeminate, yet both reactions turn on the intersection of race and gender and suggest the degree to which the dominant culture was both fascinated and threatened by the sexuality of non-white men. The romantic/sexual union of the characters Valentino played and the white female leads in his films could place only within the confines of the exotic and the ahistorical, tings which paradoxically emphasized and sanitized his otherness. Indeed, the very term Latin Lover-which Valentino is thought personify-is a distillation of this paradox, invoking myths sexual appetite and prowess of non-white men, while giving its ject a generic marker of classical connotation that keeps such overdetermined sexuality at a safe distance. Such strategies of containment become less surprising when one recalls that Valentino reached peak of his popularity during one of the most xenophobic periods U.S. history. But as white male reaction against Valentino intensified, the film industry found such strategies were no longer enough. sponded by attempting to create a new Valentino myth, that immigrant from humble origins who, through hard work, reaches pinnacle of success in the Melting Pot. As Studlar comments, this fort to “mainstream” Valentino was to a large extent offset by publicity imagery that visually insisted on capitalizing on eroticism unveiled”. The outcome of this conflict between peting racial and sexual ideologies was predictable, if bizarre: Holly- wood churned out a spate of copycat films about Latin Lovers, this time played by Anglo actors like Douglas Fairbanks, Ronald man and John Barrymore . And as the Latin Lover were co-opted by Anglo actors, “the assignment of pejorative nine and racist traits to Valentino intensified”. To summarize, the response to Valentino on the part of white was so hostile because not only did his persona represent a departure from traditional WASP norms of masculinity, it also engaged about sexual relations between non-white men and white women. Hollywood attempted to ameliorate those fears by a discourse of ex- oticism that made such taboo relationships safe, just as the term Latin Lover precisely connotes such forbidden love made safe by the exot- ic as much as it suggests the fusion of masculine domination with courtly manners. As Valentino’s popularity with white female moviegoers increased, so did the level of hostility toward him from white men. In the context of Sapia’s novel, it is significant that is, like Valentino, a non-Anglo immigrant to the United unlike the majority of Anglo men, an avid fan of Valentino. suggested earlier, Facundo’s possession of Valentino’s hair allows him to possess some of the star’s power over women locks him into repeating the star’s misfortunes, we can that argument with the observation that Sapia portrays traction for a white woman as a socially prohibited one, due to the same attitudes that created such animosity toward Valentino. Signifi- cantly, it is the fear of such animosity and racist reprisals that lie be- hind the decision to cover up the circumstances of the woman’s death. And there is another bizarre coincidence between the fates of Facundo and Valentino: the outpouring of grief by Valentino’s fans after his death and especially their attempt to glimpse and touch the star’s corpse as it lay in state is, as Hansen suggests, a figurative kind of necrophilia: The cult of Valentino’s body finally extended to his corpse and led to the notorious necrophilic excesses: Valentino’s last will specifying that his body be exhibited to his fans provided a fetishistic run for buttons of his suit, or at least candles and flowers from the funeral home. Significantly, it is within such an environment that Facundo meets the woman with whom he will literally engage in necrophilic excess; the hysterics at Valentino’s funeral are a figurative kind of necrophilia that mirror Facundo’s literal practice of it. And, Valentino’s funeral, as dramatized in the novel, is important for another reason as well. His body is guarded by Mussolini’s Italian fascists, foreshadow- ing the consequences of American isolationism and racism, just as the rioting and chaos of the funeral crowd foreshadows the violence and chaos of the war to follow. It is extremely ironic that Valentino, who rose to fame as a figure who could be used interchangeably in a variety of ethnic roles, would be guarded by fascist soldiers committed to a philosophy of ethnic purity. Sapia skillfully represents Valentino as a cultural icon that stands in ironic opposition to the fascist ideas of ethnic purity that are gaining currency in Europe and in some quarters of the United States. It is through such skillful use of historical context that Sapia enables Facundo’s story to operate as not just a modern fairy tale with a familiar theme, but as a critique of racist and sexist ideologies during a specific period of U.S. history. Another issue needs to be explored here, namely, Facundo’s fatal seduction of the young, unnamed woman and his willingness to cover up his role in her death. Although Facundo realizes he is responsible for her death and initially wants to tell the police what happened, he is persuaded by Mangual that given the racial climate, to do so would be to ensure his own eventual execution. As Mangual puts it: You are a Puerto Rican, Nieves. You are not welcome in Nueva York. You are an outsider. In the eyes of the Americans you just killed an American white woman, a white woman they would tell you, you never should have been with. What do you think they will do to you? They’ll say you lured her here, Nieves. They’ll say you sexually attacked her her. They’ll say you murdered her. …You feel guilty, of course. don’t blame you, Nieves. But look what they do to immigrants, to foreigners like us. For Christ’s sake, look what’s happened to those two Italians, Sacco and Vanzetti. Take it from me, hombre, they’re two men. And you will be too. They’ll crucify you, Nieves, and they’ll your balls off and shove them down your throat to make sure you dead. This argument is a bit slippery. While the white society of the racist and very probably would react as Mangual suggests (as the erence to Sacco and Vanzetti reminds us), such a position glosses over the fact that Nieves did lure the woman to his barbershop, drug her for the purpose of taking advantage of her, did sexually tack her and did cause her death. Nor does Sapia ever provide dence to suggest that racist sexual taboos were behind the woman’s lack of interest in Nieves. Consider also, that even after this tragedy, Nieves continues to use the talisman, seducing at least two women with it. He admits to his eldest child, Barbara, that he “magic” to cause his second wife to marry him and it is intimated that years later, shortly before his death, he uses the hair to obtain wife for his friend Pancho. Yet, despite attempts to rationalize tify his crime and attempts to use the talisman benevolently, do’s role in the woman’s death and his continued use of the talisman for personal gain clearly haunt him. Ultimately he is compelled by guilt to give an accounting of his actions. Significantly, the catalyst for Facundo’s confession is Valentino himself. After watching one of Valentino’s movies on the late late show, Nieves suffers a seizure and slips into a coma, during which time he mysteriously confesses his actions and his culpability to his son. The importance of this act is clear, as Facundo dies just moments after completing the confession, the final words of which suggest that he is now at peace: “Now, my boy, good-bye, good-bye. There’s a little boat waiting for me. I hear the dew falling in the rain forest. I hear voices echoing in the dark cool coves. The earth smells like a good place. Recuerdame, Lupe. After Facundo’s death, Lupe buries the last remnants of Valentino’s hair with his father in a gesture that suggests that al- though the father and son may be one, as Facundo was fond of saying, the son is not destined to repeat the mistakes of the father. Moreover, Sapia represents the idea that no one is beyond redemption. Nevertheless, there is something about this tidy ending which rings a bit hollow. To uncover the source of this dissatisfaction, I believe it is necessary to consider Lupe’s story in relation to his father’s. Significantly, most of the scenes in which Lupe is present have to do with his coming of age. He witnesses the tragic deaths of neighbors in a fire and learns that unrequited love can drive men to kill them- selves. He witnesses the unhappiness of immediate family members: his mother, who is saddened to tears by the loss of her youthful beauty; the fear of motherhood of his young, pregnant aunt Miriam, whose boyfriend has left her; and the cynicism of his grandmother Sofia, whose children have died at young ages. And he learns that his father and uncle were thrown out of their parents’ house when they came of age. However, although Lupe empathizes with his relatives, their experiences do not make him timid or fearful. Instead he draws strength from their experiences. All of this is made possible because Lupe remains firmly grounded in his Puerto Rican community. Yet, this insularity is precisely the element that causes the ending of the novel to appear overly optimistic. Lupe’s experiences have all taken place within the confines of that tightly-knit Puerto Rican communi- ty and he has been completely sheltered from any contact with the world outside of it. Early in the novel, Sapia addresses Lupe’s sheltered upbringing in an intriguing scene in which his stepsister Barbara refers to him as “colored,” a term that puzzles Lupe. To him, Barbara’s whiteskinned, rosy cheeked daughter is more colored than he is. However, after this childhood incident, Lupe does not have any more interaction with anyone from outside of his community. It is this lack of attention to relations between Puerto Ricans and other ethnic groups in Lupe’s narrative that leaves the reader with some reservations regarding Sapia’s suggestion that Lupe will not re- peat his father’s mistakes. Moreover, given the skillful treatment of race relations in Facundo’s narrative, the lack of attention to interracial issues in Lupe’s story stands out as a noticeable oversight. While the depiction of the Puerto Rican community as a source of strength, comfort and knowledge for Lupe is powerful and moving, his isola- tion from the outside world is disturbingly similar to the xenophobia that Sapia critiques so well elsewhere in the novel.

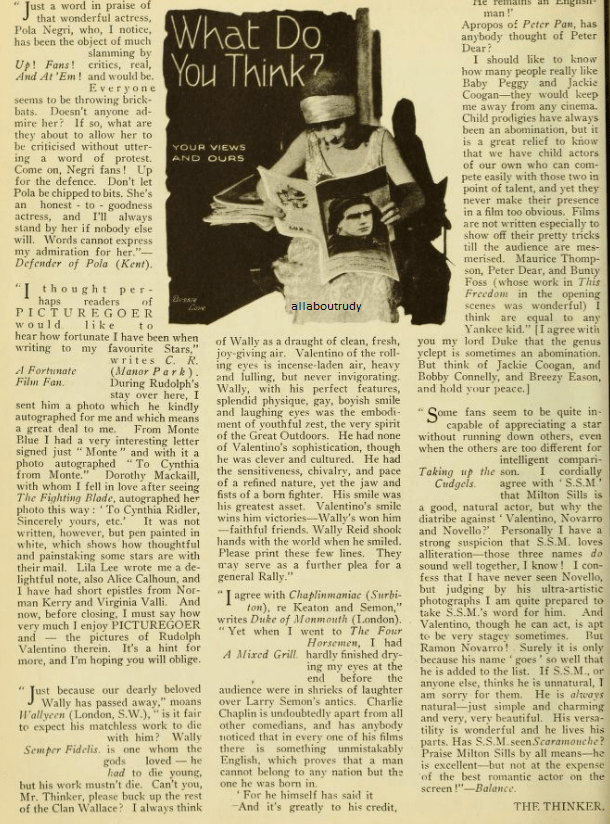

Oct 1923 – What do you think?

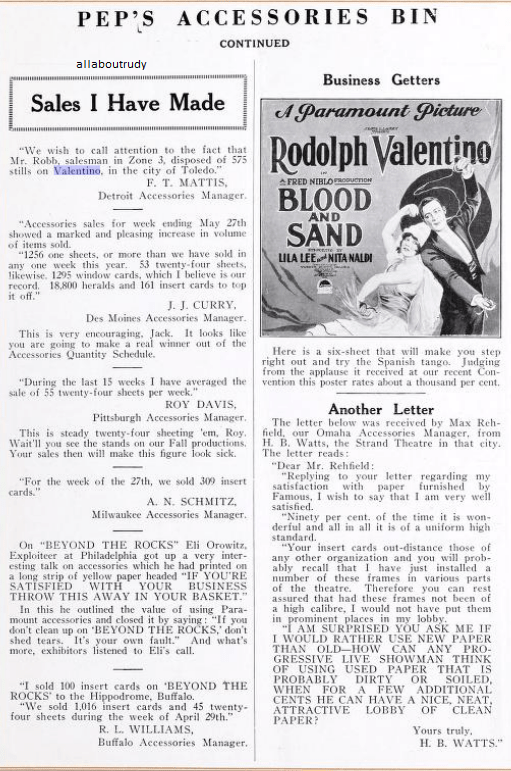

29 Sep – Silent Movie Day Rudolph Valentino Movies

What does this day have in common with Rudolph Valentino? According to the official Silent Movie Day website “Silent Movie Day is an annual celebration of silent movies, a vastly misunderstood and neglected cinematic art form”. We celebrate Valentino’s life annually and of course his life has been both publicly and personally misunderstood and his movies have been neglected by the cinema community. When I try to speak with anyone about my interest in silent films, I see a disinterested look on their face. Immediately I feel like why waste time speaking with someone who doesn’t understand a cinematic artform that is the very cradle of the Hollywood movie industry. But for those rare few who mutually agree, there is something special and mysterious about Silent Films it’s wonderful to have these meaningful conversations that are both enlightening and rewarding. Sometimes, I feel unless one lives in the L.A. area to celebrate what is left of Hollywood history by attending cinematic events or exhibits, they are left out and I do agree with this. For example, when the unfortunate pandemic hit the world a few years ago, everyone had to adjust the way things were ran. Virtual events were available everywhere, and I felt blessed to be able to see Silent Film festivals online. Nowadays they are no longer available and trying to find out about new virtual events is hard. Recently I posted a question in a silent film related social media group innocently asking about “where could I go to see what silent film events are online” my question was both deleted, and I am no longer a member of this group. Now am I offended? No, it doesn’t because there is such a decent lack in humanity these days and I see this in the real and virtual worlds. I often think how Valentino must of felt in his professional and personal life when things didn’t exactly turn out how they might. Sometimes we have no choice but to live and let live. Letting go and moving on are indeed the best route to take. For this special day, Silent Films are a joy to watch, and the beauty is in the acting and movie plots. Take a moment and enjoy a Rudolph Valentino movie.

25 Sep 1926 – Diseuse a la Francasise

Mlle Damia, a friend of Rudolph Valentino’s and a diseuse from Paris, made her American debut at the Forty-Ninth Street Theatre yesterday afternoon in a private recital of songs chiefly on tragic themes. In a brief introduction, Henry E. Dixey commented upon Mlle. Damia’s skill in a pantomime and, obviously referring to Raquel Meller, asked the audience to receive her on her own terms. However, fair that request may be, one can hardly report Mlle without comparing her to la Meller, whose art, technically, hers resembles so closely. Like Meller she appears alone before a black drop curtain and sings dramatic poems, accompanied by a string orchestra. In appearance Mlle Damia is less exotic; and her art is emotional rather than strangely vibrant. For ten years of so Mlle Damia has been appearing as a “lyric tragedienne” on Paris stages as one number in a program. Obviously, that is the most practical way to present her, the first half of the program yesterday afternoon, consisting of rather turgidly emotional songs, did not express the most attractive qualities of her pantomimic abilities. Although an undercurrent of tragedy ran through the second half of the program, the songs were lighter and better contrasted. Singing the colorful “La Femme a la Rose,” Mlle Damia was particularly pungent in her expression of character. In “La Supplane,” a war mother hunting her for her sons grave, she communicated admirably the pathos and agony of so tragic a figure. “La Fanchette” represented her a s a sailor who has determined to murder his unfaithful mistress; in this song Mlle. Damia was graphically pictorial. Her most spirited number was the rather macabre “Les Deux Menetriers,” written by Jean Richepin; Mlle Damia described it perfectly. Unfortunately, we in America have little of the pantomimic tradition in our stage life; and, no doubt, few of the qualities of judgment necessary to appreciative reception. Like chamber music, it is for those who catch the overtones and the nuances. Mlle Damias art has fullness. Beyond the symmetry of gestures and the plasticity of facial expression there is a firm solidity. If she lacks the versatility of a virtuoso, she is nevertheless thorough; and if she is not capricious, she is frank and profound. Our revue stage would profit by a regular expression of her art. Contrasted with more usual and blatant numbers of the familiar revue, Mlle Damia’s art would emerge as a pleasing expression of quality.

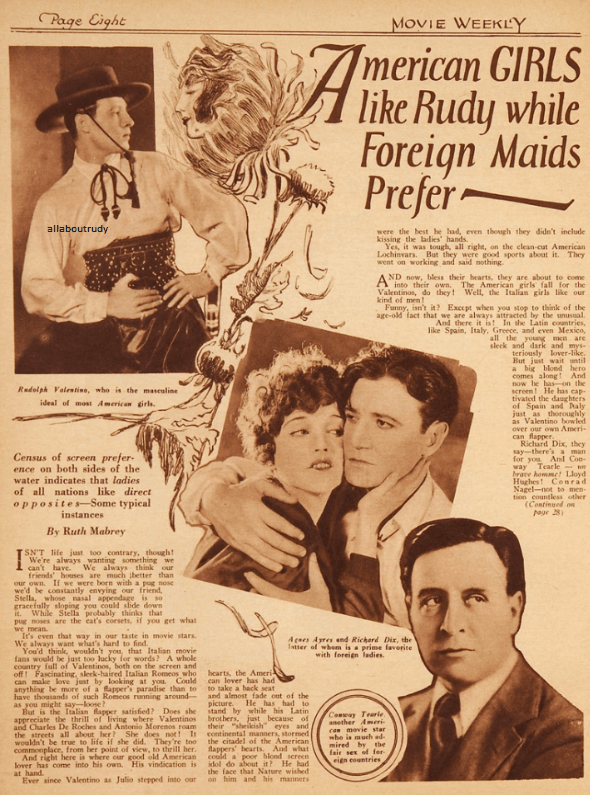

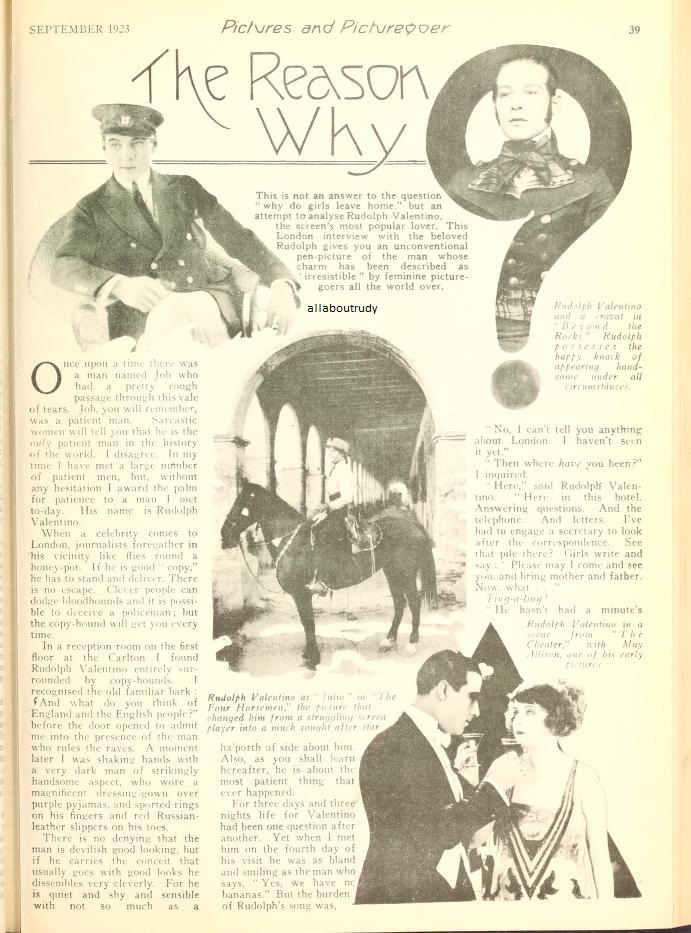

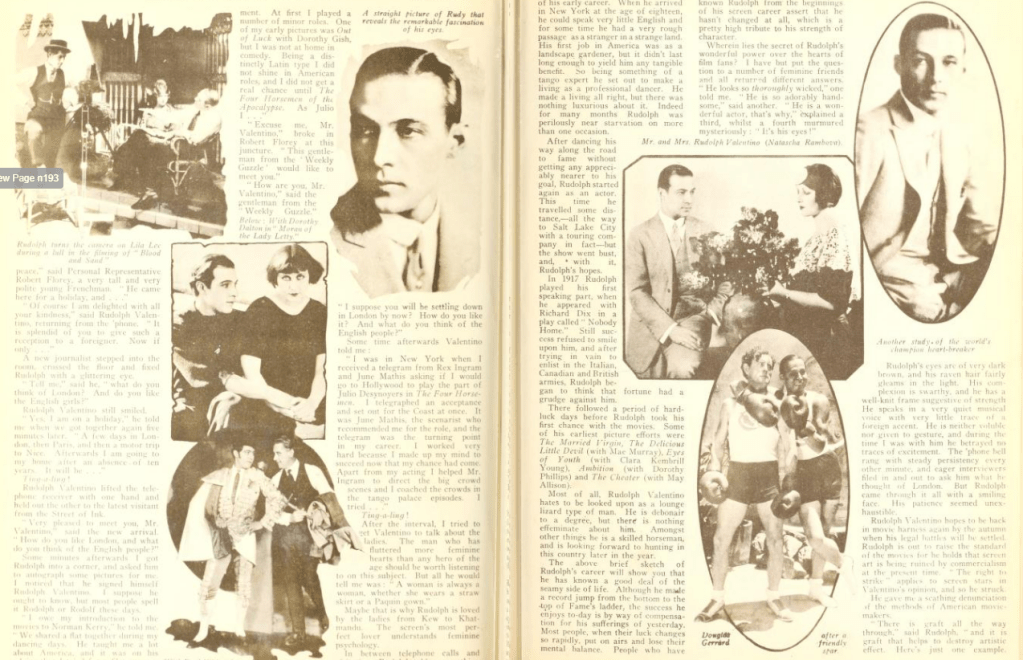

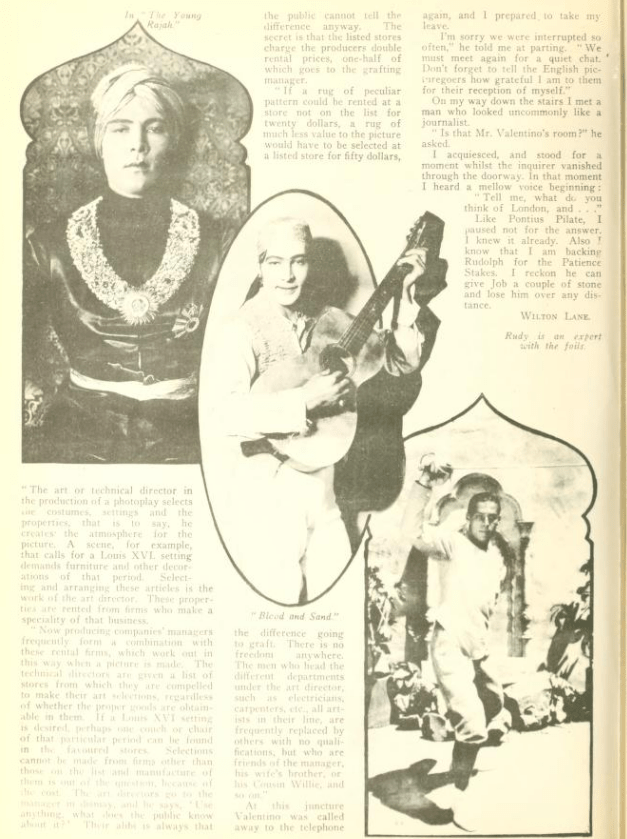

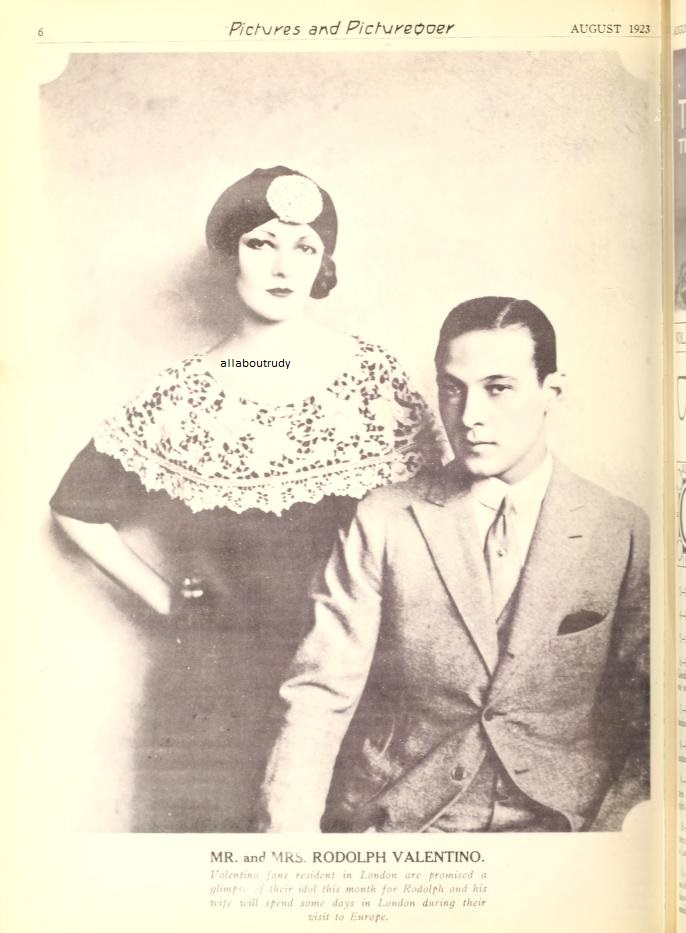

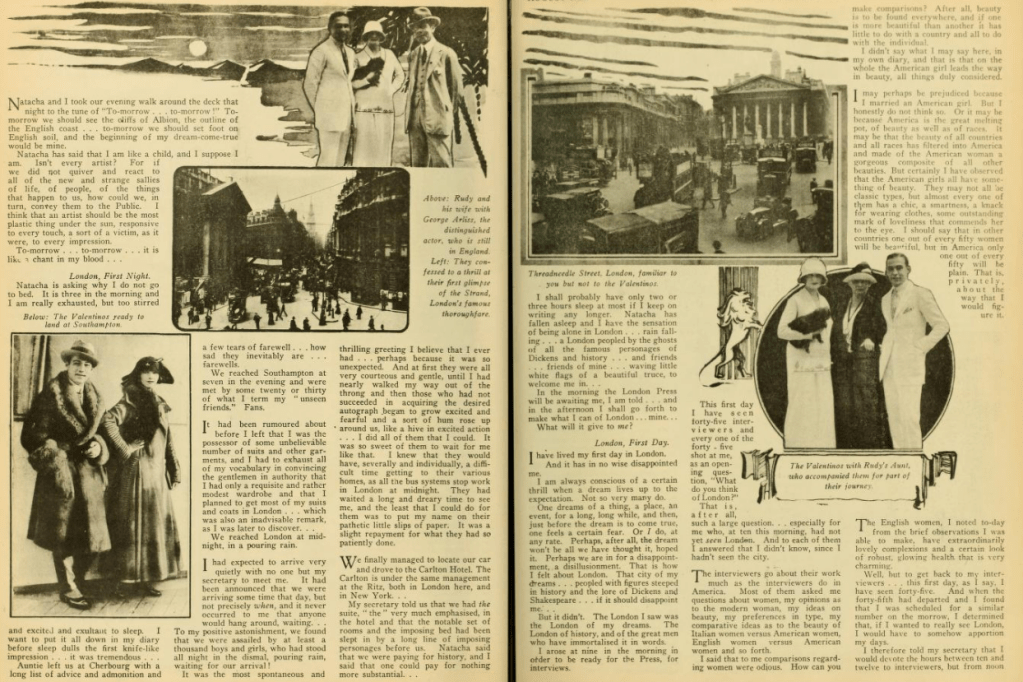

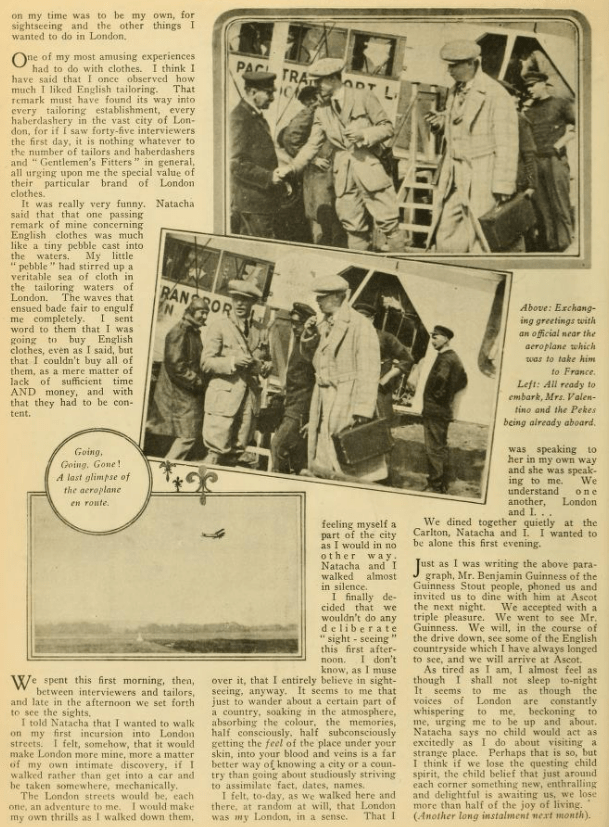

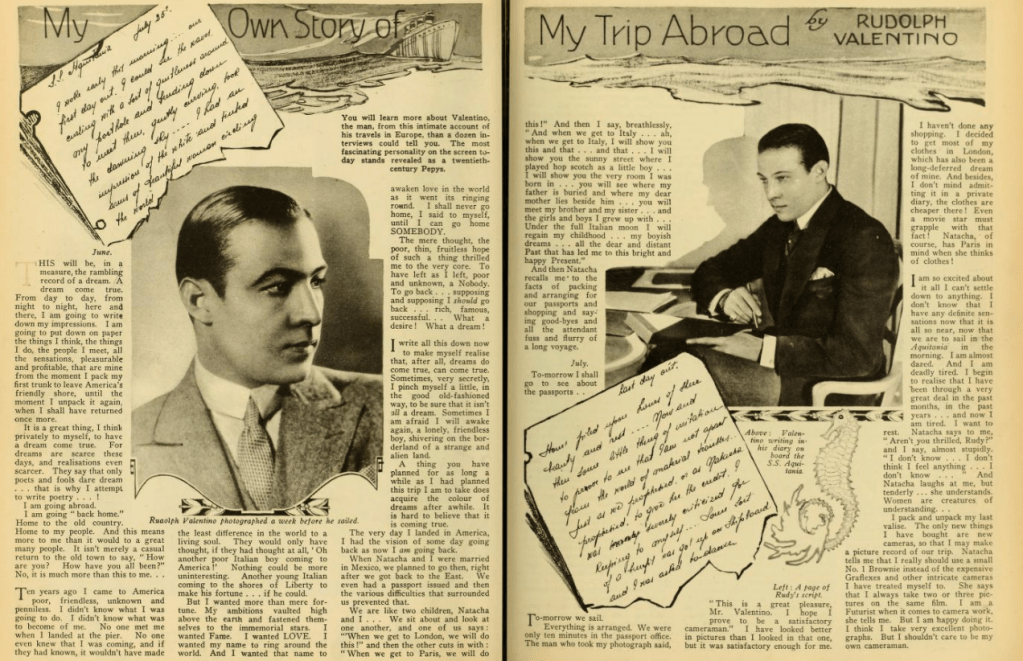

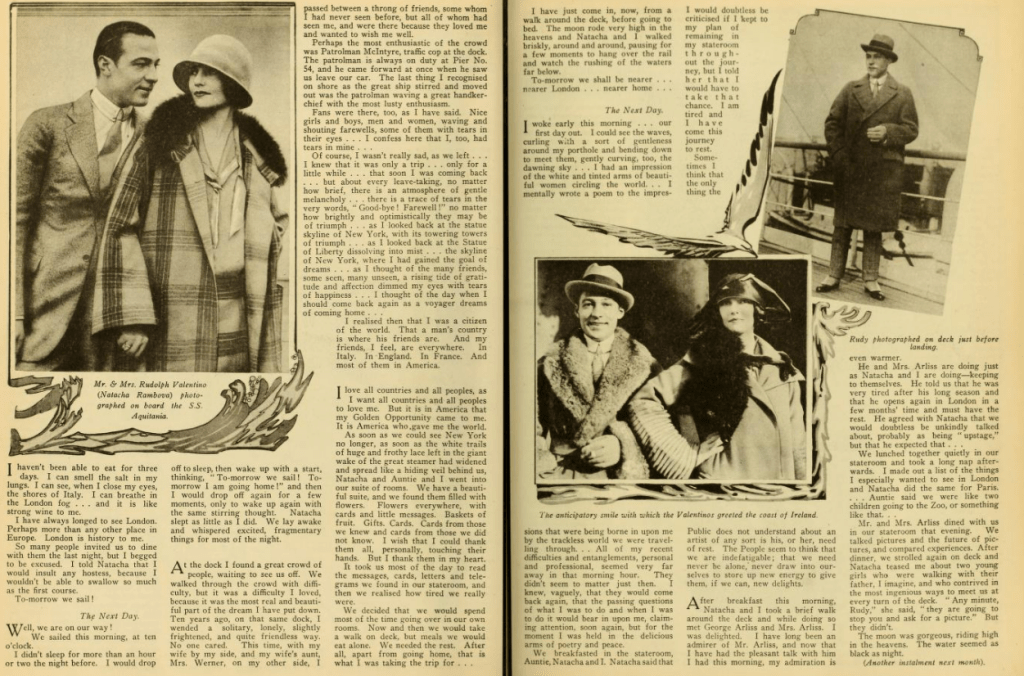

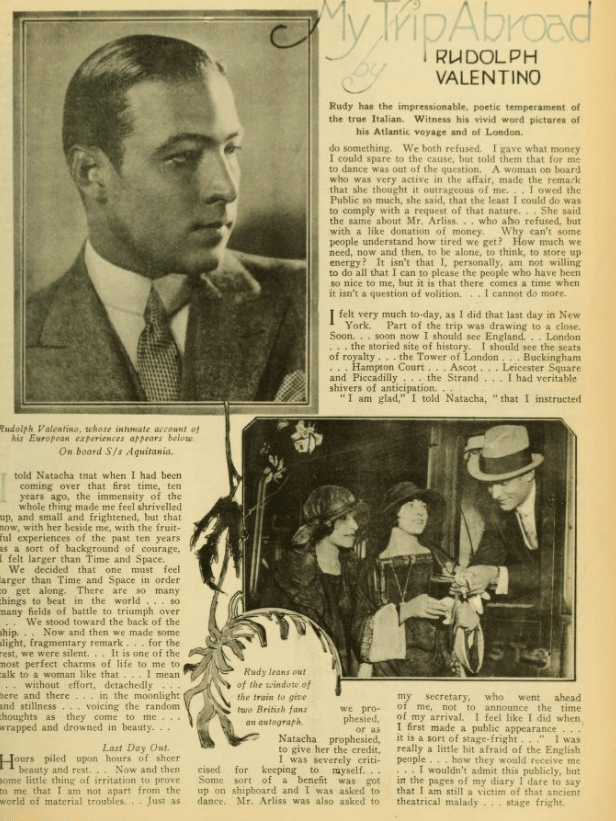

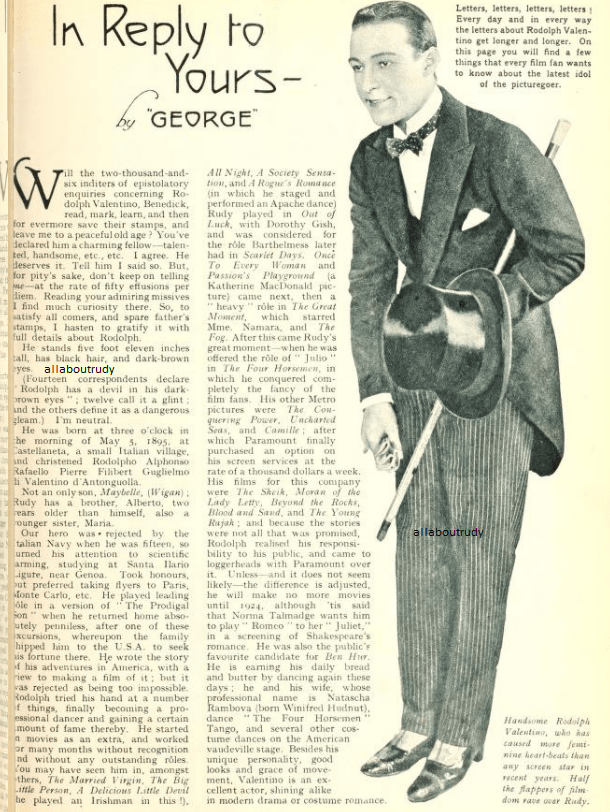

Sep 1923 – The Reason Why, Pictures & Picturegoer Magazine

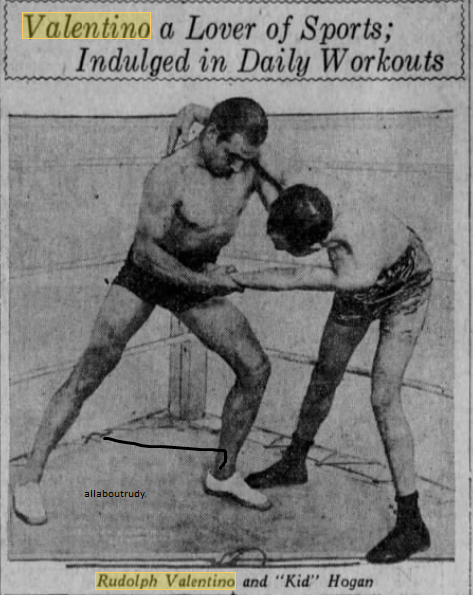

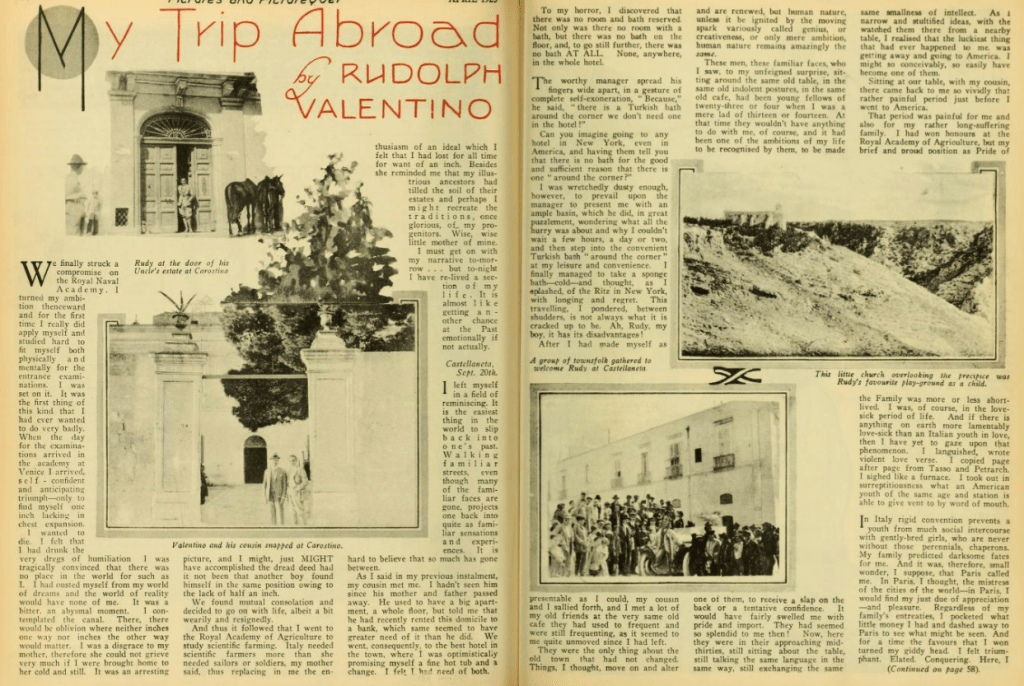

This is not an answer to the question “why do girls leave home,” but an attempt to analyse Rudolph Valentino, the screen’s most popular lover. This London interview with the beloved Rudolph gives you an unconventional pen-picture of the man whose charm has been described as “irresistible” by feminine picturegoers all the world over. Once upon a time there was a man named Job who had a pretty rough passage through this vale of tears. Job, as you remember, was a patient man. Sarcastic women will tell you that he is the _only_ patient man in the history of the world. I disagree. In my time I have met a large number of patient men, but without any hesitation I award the palm of patience to a man I met to-day. His name is Rudolph Valentino.When a celebrity comes to London, journalists foregather in his vicinity like flies round a honeypot. If he is good “copy,” he has to stand and deliver. There is no escape. Clever people can dodge bloodhounds and it is possible to deceive a police officer; but the copy-hound will get you every time. In a reception room on the first floor at the Carlton I found Rudolph Valentino entirely surrounded by copy-hounds. I recognised the old familiar bark: “And what do you think of England and the English people?” before the door opened to admit me into the presence of the man who rules the raves. A moment later I was shaking hands with a dark man of strikingly handsome aspect, who wore a magnificent dressing-gown over purple pyjamas, and sported rings on his fingers and red Russian-leather slippers on his toes. There is no denying that the man is devilish good looking, but if he carries the conceit that usually goes with good looks he dissembles very cleverly. For he is quiet and shy and sensible with not so much as a ha’porth of side about him. Also, as you shall learn hereafter, he is about the most patient thing that ever happened. For three days and three nights life for Valentino had been one question after another. Yet when I met him on the fourth day of his visit he was as bland and smiling as the man who says, “Yes, we have no bananas.” But the burden of Rudolph’s song was, “No, I can’t tell you anything about London. I haven’t seen it yet.”Then where _have_ you been?” I inquired. “Here,” said Rudolph Valentino. “Here in this hotel answering questions. And the telephone. And letters. I’ve had to engage a secretary to look after the correspondence. See that pile there? Girls write and say: “Please may I see you and bring your mother and father. Now what.”Ting-a-ling! He hasn’t had a minute’s peace, said Personal Representative Robert Florey, a very tall and very polite young Frenchman. “He came here for a holiday, and “Of course I am delighted with all your kindness, ” said Rudolph Valentino, returning from the ‘phone. “It is splendid of you to give such a reception to a foreigner. Now if only.”A new journalist stepped into the room, crossed the floor and fixed Rudolph with a glittering eye. “Tell me,”said he, “what do you think of London? And do you like the English girls?” Rudolph Valentino still smiled. “Yes, I am on a holiday,” he told me when we got together again five minutes later. “A few days in London, then Paris, and then a motor trip to Nice. Afterwards I am going to my home after an absence of ten years. It will be.”Ting-a-ling! Rudolph Valentino lifted the telephone receiver with one hand and held out the other to the latest visitant from the Street of Ink. “Very pleased to meet you, Mr. Valentino,” said the new arrival. “How do you like London, and what do you think of the English people?” Some minutes afterwards I got Rudolph into a corner and asked him to autograph some pictures for me. I noticed that he signed himself Rudolph Valentino. I suppose he ought to know, but most people spell it Rodolph or Rodolf these days.”I owe my introduction to the movies to Norman Kerry,” he told me. “We shared a flat together during my dancing days. He taught me a lot about America, and it was on his advice that I tried for a film engagement. At first, I played a number of minor roles. One of my early pictures was “Out of Luck” with Dorothy Gish, but I was not at home in comedy. Being a distinct Latin type I did not shine in American roles, and I did not get a real chance until “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.” As Julio I “Excuse me, Mr. Valentino,” broke in Robert Florey at this juncture. “This gentleman from the ‘Weekly Guzzle’ would like to meet you. “How are you, Mr. Valentino?” said the gentleman from the “Weekly Guzzle.” “I suppose you will be settling down in London by now. How do you like it and what do you think of the English people?” Sometime afterwards Valentino told me: “I was in New York when I received a telegram from Rex Ingram and June Mathis asking if I would go to Hollywood to play the part of Julio Desnoyers in “The Four Horsemen.” I telegraphed an acceptance and set out for the Coast at once. It was June Mathis, the scenarist who recommended me for the role, and the telegram was the turning point in my career. I worked very hard because I made up my mind to succeed now that my chance had come. Apart from my acting I helped Mr. Ingram to direct the big crowd scenes and I coached the crowds in the tango palace episodes. I tried “Ting-a-ling! After the interval, I tried to get Valentino to talk about the ladies. The man who has fluttered more feminine hearts than any hero of the age should be worth listening to on this subject. But all he would tell me was: “A woman is always a woman, whether she wears a straw skirt or a Paquin gown.” Maybe that is why Rudolph is loved by the ladies from Kew to Khatmandu. The screen’s most perfect lover understands feminine psychology. In between telephone calls and visitations, Rudolph told me something of his early career. When he arrived in New York at the age of eighteen, he could speak very little English and for some time he had a very rough passage as a stranger in a strange land. His first job in America was as a landscape gardener, but it didn’t last long enough to yield him any tangible benefit. So being something of a tango expert he set out to make a living as a professional dancer. He made a living all right, but there was nothing luxurious about it. Indeed, for many months Rudolph was perilously near starvation on more than one occasion. After dancing his way along the road to fame without getting any appreciably nearer to his goal, Rodolph started again as an actor. This time he travelled some distance, –all the way to Salt Lake City with a touring company in fact–but the show went bust, and, with it, Rudolph’s hopes. In 1917 played his first speaking part, when he appeared with Richard Dix in a play called “Nobody Home.” Still success refused to smile upon him, and after trying in vain to enlist in the Italian, Canadian and British armies, Rudolph began to think that fortune had a grudge against him. There followed a period of hard-luck days before Rudolph took his first chance with the movies. Some of his earlier picture efforts were “The Married Virgin,” “The Delicious Little Devil” (with Mae Murray), “Eyes of Youth” (with Clara Kembill-Young), “Ambition” (with Dorothy Phillips) and “The Cheater” (with May Allison). Most of all, Rudolph Valentino hates to be looked upon as a lounge lizard type of man. He is debonair to a degree, but there is nothing effeminate about him. Amongst other things he is a skilled horseman and is looking forward to hunting in this country later in the year. The above brief sketch of Rudolph’s career will show you that he has known a good deal of the seamy side of life. Although he made a record jump from the bottom of Fame’s ladder, the success he enjoys to-day is by way of compensation for his sufferings of yesterday. Most people, when their luck changes so rapidly, put on airs and lose their mental balance. People who have known Rudolph from the beginning of his screen career assert that he hasn’t changed at all, which is a pretty high tribute to his strength of character. Wherein lies the secret of Rudolph’s wonderful power over the hearts of film fans. I have but put the question to a number of feminine friends and all returned different answers. “He looks so _thoroughly_ wicked,” one told me. “He is so adorably handsome,” said another. “He is a wonderful actor, and that’s why,” explained a third, whilst a fourth murmured mysteriously: “It’s his eyes!” Rudolph’s eyes are of very dark brown, and his raven hair fairly gleams in the light. His complexion is swarthy, and he has a well-knit frame suggestive of strength. He speaks in a very quiet musical voice with very little trace of a foreign accent. He is neither voluble nor given to gesture, and during the time I was with him he betrayed no traces of excitement. The ‘phone bell rang with steady persistency every other minute, and eager interviewers filed in and out to ask him what he thought of London. But Rudolph came through it all with a smiling face. His patience seemed inexhaustible. Rudolph Valentino hopes to be back in movie harness again by the autumn when his legal battles will be settled. Rudolph is out to raise the standard of the movies for he holds that screen art is being ruined by commercialism at the present time. “The right to strike” applies to screen stars in Valentino’s opinion, and so he struck. He gave me a scathing denunciation of the methods of American moviemakers. “There is graft all the way through,” said Rudolph, “and it is graft that helps to destroy artistic effect. Here’s just one example the art or technical director in the production of a photoplay selects the costumes, settings and the properties, which is to say, he creates the atmosphere for the picture. A scene, for example, which calls for a Louis XVI setting demands furniture and other decorations of that period. Selecting and arranging these articles is the work of the art director. These properties are rented from firms who make a specialty of that business. “Now producing companies’ managers frequently form a combination with these rental firms, which work out in this way when a picture is made. The technical directors are given a list of stores from which they are compelled to make their art selections, regardless of whether the proper goods are obtainable in them. If a Louis XVI setting is desired, perhaps one couch or chair of that particular period can be found in the favoured stores. Selections cannot be made from firms other than those on the list and manufacture of them is out of the question, because of the cost. The art directors go to the manager in dismay, and he says, “Use anything, what does the public know about it?” Their alibi is always that the public cannot tell the difference anyway. The secret is that the listed stores charge the producers double rental prices, one-half of which goes to the grafting manager. “If a rug of particular pattern could be rented at a store not on the list for twenty dollars, a rug of much less value to the picture would have to be selected at a listed store for fifty dollars, the difference going to graft. There is no freedom anywhere. The men who head the different departments under the art director, such as the electricians, carpenters, etc., all artists in their line, are frequently replaced by others with no qualifications, but who are friends of the manager, his wife’s brother, or his cousin Willie, and so on. “At this juncture Valentino was called away to the telephone again, and I prepared to take my leave. “I’m sorry we were interrupted so often,” he told me at parting. “We must meet again for a quiet chat. Don’t forget to tell the English picturegoers how grateful I am to them for their reception of myself. “On my way down the stairs I met a man who looked uncommonly like a journalist. “Is that Mr. Valentino’s room?” he asked. I acquiesced and stood for a moment whilst the inquirer vanished through the doorway. In that moment I heard a mellow voice beginning: “tell me, what do you think of London, like Pontius Pilate, I paused not for the answer. I knew it already. Also, I know that I am backing Rudolph Valentino for the Patience Stakes. I reckon he can give Job a couple of stone and lose him over any distance.

Sep 1923 – What do you think?

Aug 1923 – What do you think?

I have seen my favourite actor in my favourite book, which is Rodolph Valentino in “The Sheik”, and both were splendid. But Agnes Ayres spoilt the film, she was nothing like the character “Diana” of the book. She did not have the look, or the personality and I was hoping for someone more believable. Eileen Percy would have been lots better. Why have the producers spoiled a splendid film by mis-casting the heroine in this fashion?

From Susanne Yorkshire

July 1923 – What do you think?

I think that Rodolph Valentino is the finest actor this century has known so far. BUT not the handsomest. In fact, I don’t like his looks at all. But in my opinion, Thomas Meighan is the best looker.

From Mary, Isle of Wight

Why on earth, when they are filming a movie based on a book a movie studio bought the rights too don’t they keep it exactly like the book? I have seen “The Sheik” and I think it is so terribly disappointing to film fans when they go to see a favourite novel screened and find it hardly recognizable. Also, why cast Valentino and Agnes Ayres in “The Sheik”? both are favourites of mine, but they did not put enough ‘pep’ into their respective roles.

From James, Scotland

30 Jun 1923 – Utah Mineralava Contest Announcement

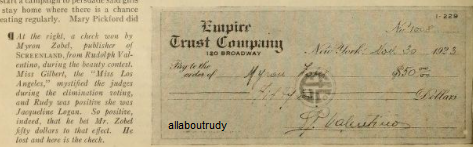

1923 – Mineralava Tour Check

25 Jun 1923 – Valentino Come Back

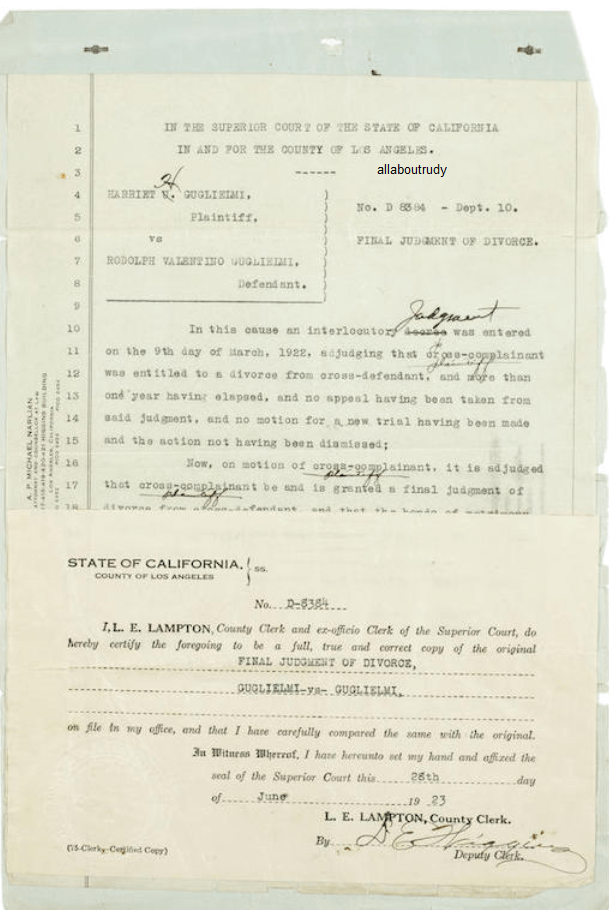

1923 – June Acker vs. Rudolph Valentino

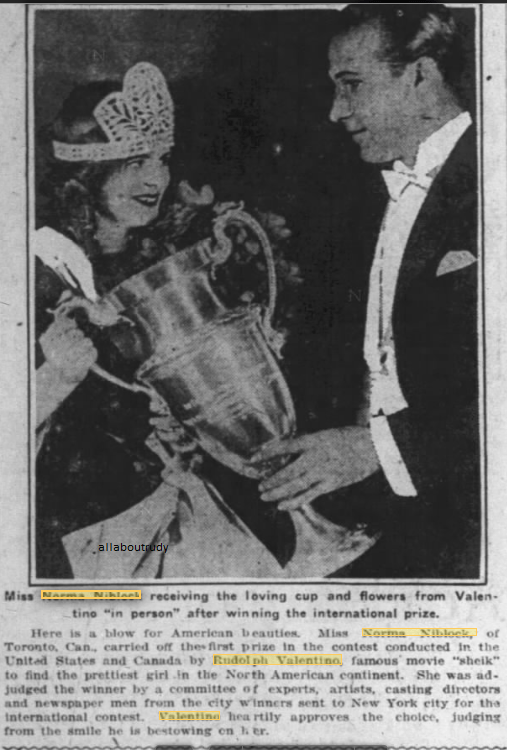

20 Jun 1923 – Mineralava Beauty Contest Annoucement, Atlanta, Georgia

1930 – Director Robert Vignola testifies

Motion picture director Robert Vignola testifies in a civil case involving the estate of Rudolph Valentino. Mr. Vignola is an Italian born friend of the late Valentino. Mr. Vignola directed Rudolph Valentino in an uncredit role in the 1916 silent film titled “Seventeen”. After the late actor’s death, Mr. Vignola and a group of fellow Italians to no avail tried to have an Italian Park constructed in Valentino’s memory.

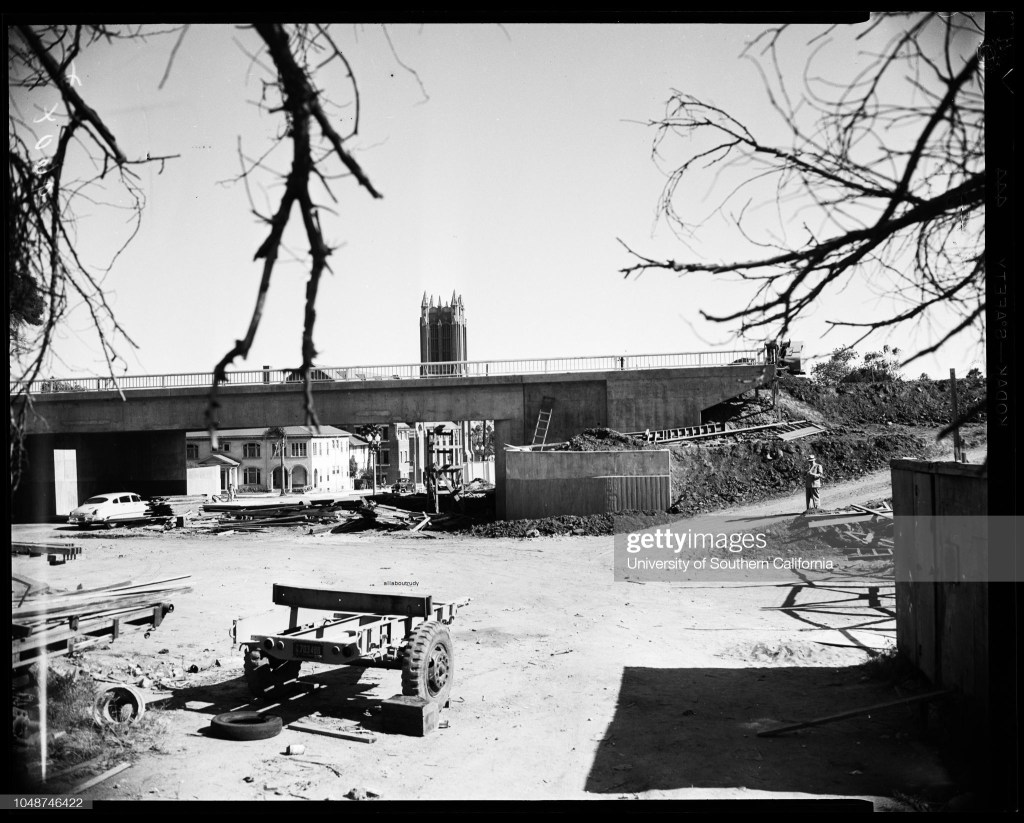

10 Jun 1952 – Whitley Heights Home Torn Down

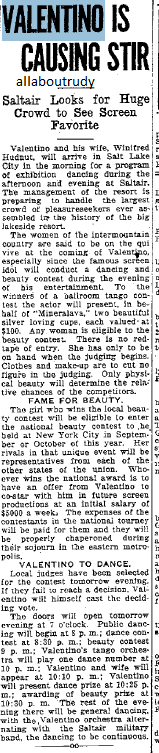

5 June 1923 – Mineralava Beauty Contest Annoucment, Salt Lake City, Utah

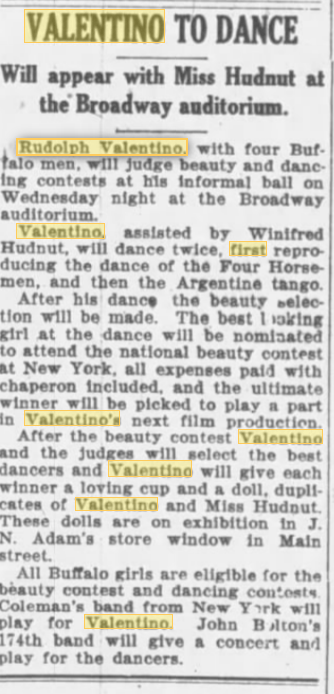

Jun 1923 – Mineralava Beauty Contest Annoucement, Buffalo, New York

Jun 1923 – Mineralava Beauty Contest Winner Annoucement, Washington State

June 1923 – What do you think?

I am writing in response to an opinion published in your movie magazine by Lance C. The tripe he wrote annoyed me by saving we girls are changeable and fickle. That when we eulogise a new film star, we immediately forget the old favourites. I’m most awfully fond of nearly a dozen fine film stars, and yet I’ve tons of room in my heart for Rodolph Valentino. Please tell the world, that we girls have elastic hears and can cram no end of loves inside for anybody but the worthless idiot Lance C after his cutting and quite inexcusable remarks. No one with a nice name like that ought to say nasty things about girls. Don’t you think I’m quite right? About the elastic hearts, most certainly I do.

From Betty, Dorset

30 May 1923 – Mineralava Tour Announcement, Seattle, WA

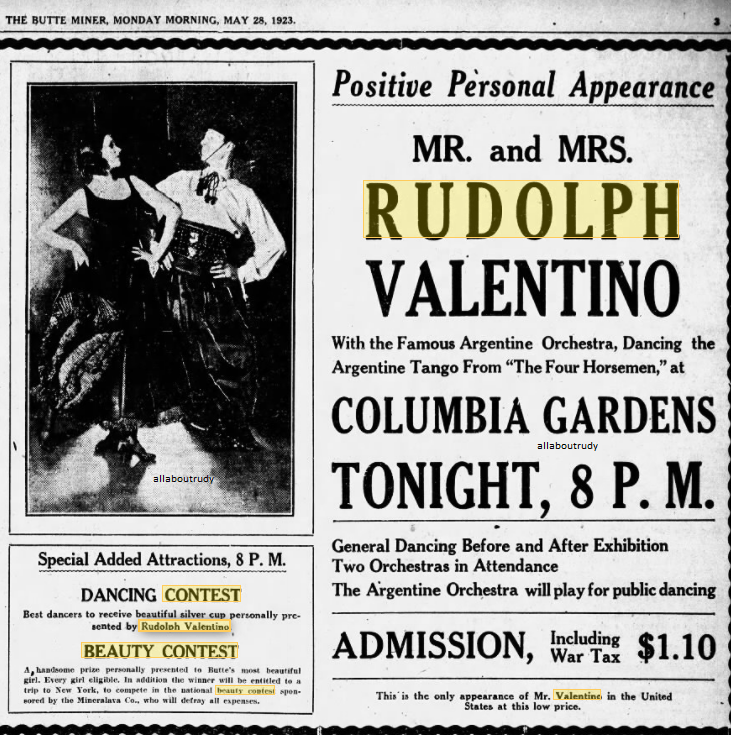

28 May 1923 – Mineralava Beauty Contest Annoucement, Montana

26 May 1929 – Mystics Rule Hollywood

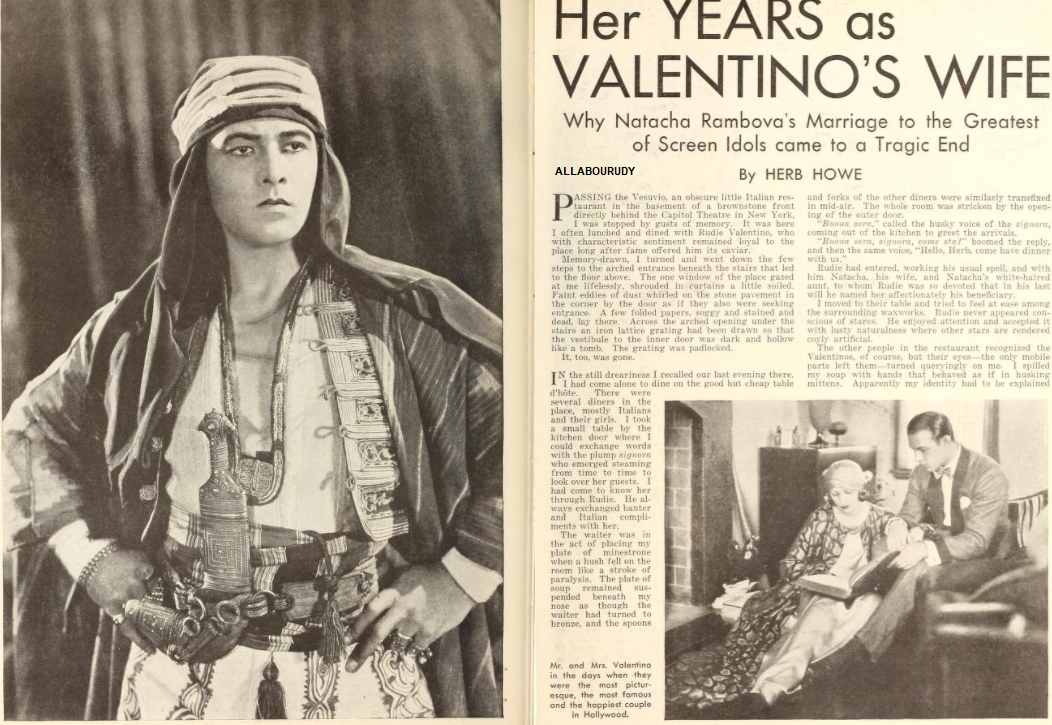

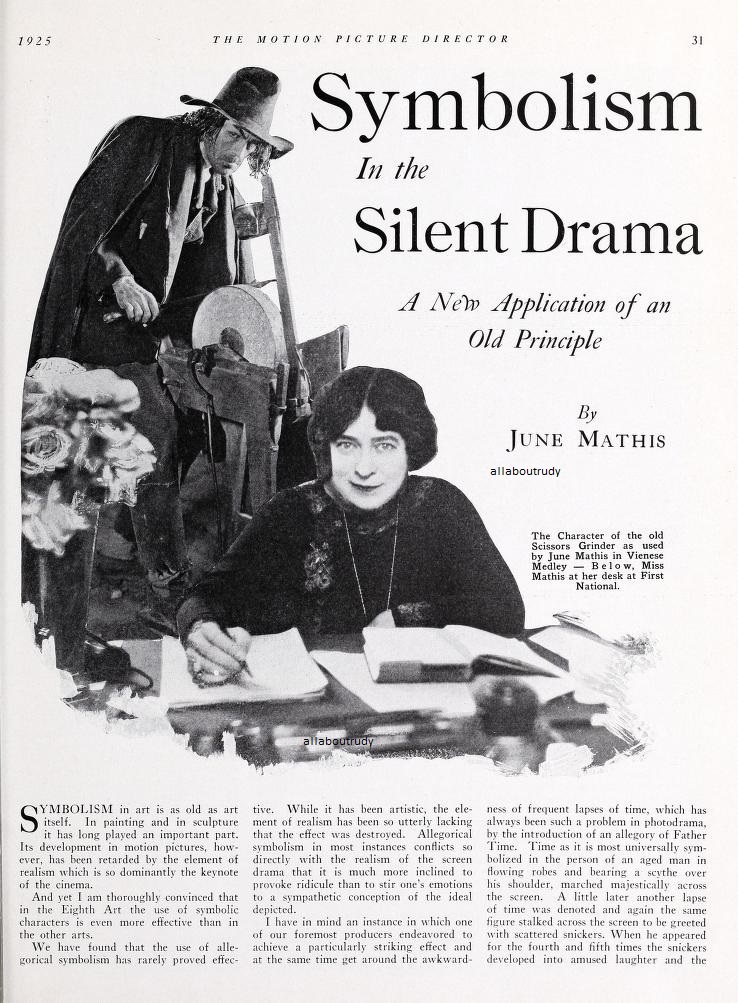

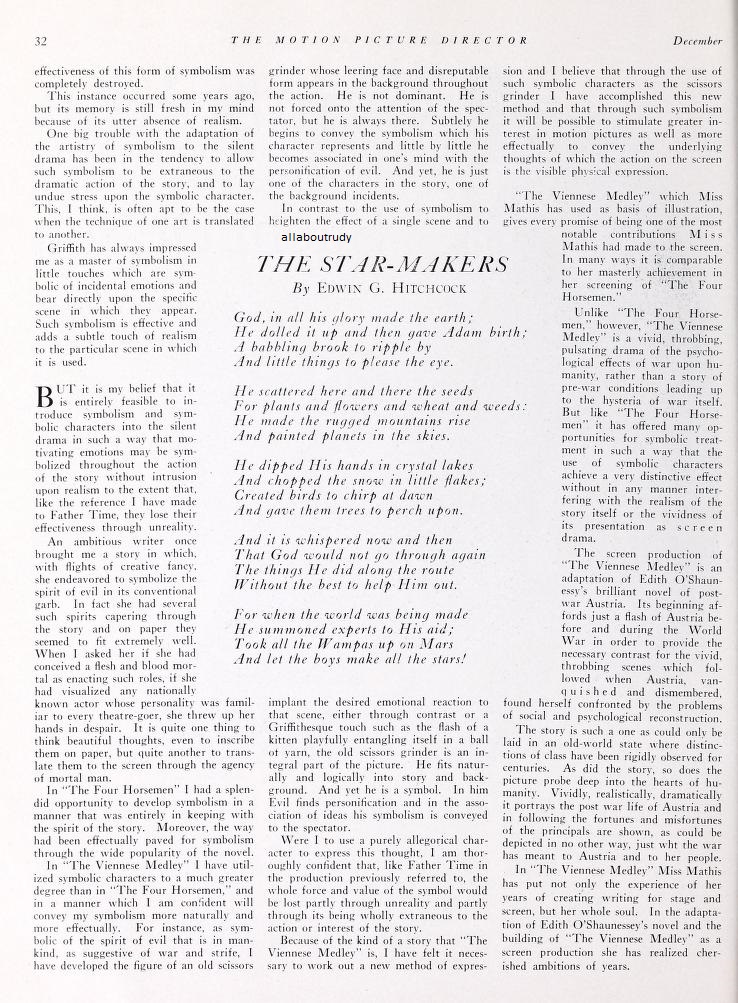

The lines are forming at the right before the séance chambers of Hollywood soothsayers. Hollywood elite do not advertise going to the occult in order to see what the fates have in store. Norma Talmadge introduced noted psychic Dareos to the film colony. foretold of Chaplin’s numerous marital troubles and promised Mae Murray she would have a baby by husband noted fake Prince M’Divani. Soothsaying has always thrived in Hollywood and now its faring better than ever before. Dareos makes such a good living that he is now both well fed and well-dressed living in a large home in Ocean Park. Some players will not sign new movie contracts without consulting their favourite palmist, card reader or spirit guide. Astute producers will not begin new pictures unless their trusted astrologist tells them when the stars are favorably disposed. From ping-pong to mysterious seances, crystal gazing, numerology, phrenology and palmistry, the film colony goes into its anxious attempts to peer into the uncertain tomorrow. Louise Fazenda introduced numerology as a fad and for several years was all the rage. Phrenology was a favourite of Wally Reid, Eugene O’Brien, and Tom Mix and seances had its time. The beautiful Laurel Canyon home of the late Rudolph Valentino was a setting for many a search into the hereafter. June Mathis and her mother, Rudolph Valentino, Natacha Rambova all devoutly believed in their seances. They usually met alone since communicating with the other world was not just a passing fancy with them as it was with the rest of Hollywood. Indeed, since Valentino’s death Natacha often declares to the news reporters she is in close touch with Rudy in the spiritual realm. The Ouija Board came to town and many movie people sat for hours over it. However, movie stars that seek advice from these so-called mystics, soothsayers, or psychics who may or not be correct. On the other side of the coin, these psychics are living just as good as the people who pay them.

23 May 1923 – Mineralava Tour Award Selection

22 May 1923 – Mineralava Beauty Contestant Appearance, San Angelo, Texas

May 1923 – Washington State Winner Mineralava Beauty Contest

13 May 1935 – Former Mother-in-law died

10 May 1923 – Broke Star wouldn’t donate

According to a Waterbury newspaper, no star of the screen ever received the panning and knocks that were handed out last week, following the appearance of Rodolph Valentino, and, in fact before he had left town after his engagement with his Mineralava Dance Tour. The kicks at the Sheik are due to his refusal to contribute to a fund being raised by Waterbury post of the American Legion, saying that he was “up against it financially” and declined to contribute or sign a pledge card and was reported as not being in the position to do so and with refusing to give the sum of $1. It was understood that he received $1,000 for his engagement—appearing less than a half hour in his dancing act with his wife. AA very patriotic person indeed that is more concerned with what is in his pocket than his fellow man.

You must be logged in to post a comment.