When Natacha Rambova beautiful but practically unknown dancer and costume designer, became the bride of Rudolph Valentino at a hurry-up wedding on the downside of the Mexican border a couple of years ago, she was probably the most envied woman in America. “Imagine being the Sheik’s wife” said feminine movie fans. “Some women have all the luck and who is she anyway”? They heard she was a society girl interested in a career, Winifred Hudnut, stepdaughter of the perfume maker. They also heard that she had taken over the business end of Rudy’s work and was doing a very good job as adviser and general manager. Then word went out the Sheik and his wife had separated. She’d gone to Paris for a divorce. The most romantic marriage in America was all over. “Professional Jealousy” said the fans then. Each of them was afraid of losing prestige to the other and there you are! But professional jealousy was only a contributing cause; it was one of the pinpricks that widened the rent in the fabric of the Valentino’s marital relationship. The rent, says the exotic Natacha, was decreed by destiny. It’s part of an amazing story she tells; a story of ancient associations in a bygone century; the mystic doctrine of reincarnation; of the inexorable law of karma. “Rudy and I separated” she said, “because our time together in this life had run out. We came together because there was something some problem, perhaps left over from a past life to be worked out. I was necessary to him and possibly he was necessary to me. “I have no idea what the problem was. It was not given to us to know the details in this scheme of fate. But I do know that it is over. The problem was solved for all time. I do not believe that we will ever meet again in any future existence. Mrs. Valentino talked with curious oriental calm, her long dark eyes shining. She was tall and slender flowing in black satin, embroidered with mauve and pearl gray. A twist of black silk was wound around her head, turban-wise. She was like a figure from a Chinese vase in an incredible setting of black and orange. Black rugs; a black taffeta divan; orange silk against the windows and the sun coming over New York roofs. A figure of Krishnu against one wall opposite an antique Virgin and Child across the room. Leda and the Swan in porcelain, almost life-size; queer Chinese prints. The only modern touch in the room was a big sheaf of American beauty roses. And the girl who calls herself “Natacha” because she resents the commonplaceness of “Winifred” rested against black taffeta and told of the life she lived with her Sheik seven hundred years ago! Perhaps Rudy was a real Sheik then. She doesn’t know. It was in the Iberia of the Moors, before the Spaniards came down from the North and spread oppression over the land. “We lived in the south of Spain, where even today stands relics of Moorish domains” Mrs. Valentino explained. “The Moors really were Arabians, you know. I visited Spain last summer and wandered through the South. It was vaguely familiar; I felt that I was not in a strange land. You know the feeling that comes over you sometimes that you’ve been in a place before. It’s something you can’t explain by any logical means unless of course, you understand the theory of reincarnation, the progress of a spirit from life to life, working out destiny in new bodies under new conditions and environment. “What we are today is what we have worked out in the past. What we gain in each life is credited to the next, but the problems we do not solve go over to a future existence. That is Karma, the law of eternal balance. “I don’t know what my status or conditions were in medieval Spain. But I know I was a girl who was somehow in subjection”. Mrs. Valentino does not clearly remember herself in yashmak and trousers awaiting, behind harem walls the pleasure of a dark-skinned sheik resembling the handsome film hero she is divorcing. But she has a feeling of having known him at that period. “Sometime when we are ready to know everything is revealed to us” she said. I don’t know that I was married to Rudy then. But it seems likely, doesn’t it? Mrs. Valentino is astonishingly familiar with medieval Spanish and incidentally Moorish history. She declares all culture in Europe originated with the Arabs the Moors she asserts, maintain marvelous colleges in the 13th and 14th centuries and all the learned and brilliant minds of the time were Moorish. “In the day of Pedro el Cruel they were called barbarians by people who could neither read or write” she went on. “And that was when Arabic was the court language everywhere”! It is not only medieval Spain that Mrs. Valentino says she remembers however, There was an earlier existence that comes back to her through her artistic leanings and love for color. Once so long ago that she cannot guess at the century she wandered in the rose gardens of ancient Persia. “Our likes and dislikes” she explained, “are something more than just casual results of training and environment. Those things give no satisfactory reason for a very modern person preferring for example, Greek architecture to the up-to-date style of building that we have now. My own education has nothing to do with my liking for the brilliant color and bizarre mannerisms in clothes and architecture that were a part of old Persia. I have never been in the Near East, and yet I feel at home there. And I have adopted some of the customs, especially those having to do with dress, because they are perfectly natural to me. She mentioned the twist of silk she wears on her head in place of a hat. It has been two years since I have worn a hat. And a striking feature of her house costume is a long loose-fitting coat of heavy satin, embroidered in the design of peacocks and other fanciful designs associated with Persia. “Besides” she added, “I have other information about my life in Persia. It comes to me in dreams and sometimes when I am sitting quietly alone from another plane”. Like most theosophists, Mrs. Valentino believes that discarnate intelligences, known as adepts, that is, souls have worked out tall their early problems and live in a sort of lower heaven or Nirvana on the astral plane impart information to students eager to progress toward metaphysical understanding. Her special teacher, she said, is a Persian scholar who knew her when she lived in the land of Cyrus and Omar Khayyam. She says she has another and more mysterious instructor, a scholar of ancient Egypt. But she has not as yet traced her existence back to the time of the Pharaohs. “I do not associate Rudy with my Persian life” she stated thoughtfully. “Perhaps he was not incarnate at that time. Some of us have lived longer than others, you know. And, anyway, relationships change. I might have known him then, but not as a husband or lover. “I believe that my mother, in an earlier life was my sister, even now we are more like sisters than mother and daughter. She lived; I am sure in the 18th century. She has the high forehead and aquiline nose of the Bourbons. And the 18th century atmosphere is the only one she cares for or is comfortable in. A third life, which the astonishing Natacha Rambova says she remembers quite well, was the one she lived a mere 300 or so years ago in Russia. That was when she was a dancer at the imperial court and when the romantic Rudy probably was a member of the blood. Natacha has never been to Russian, but she says she understands the Russians and likes them. It was partly because of her life in Russia she said that she threw off her American name and adopted the singular one she uses professionally. She has always thought of herself as “Natacha”. And in England, a few years ago she met a young Russian dancer, Marusha Rambova who became her friend. When the girl died, she took her surname adding it to the one which she believed expressed her own personality. She explained how she was won over to the belief in reincarnation and other occult doctrines of the East. I don’t feel the slightest sadness when I think that we never, at any time or under any conditions. will be together again. I have only a sense of completion, for our karma is worked out, our problem is solved whatever it was, and our time together is over. That is why we separated.

Natacha Rambova, former wife of Silent Film Star Rudolph Valentino died on 5 June 1966 in Pasadena, California. Today, her will went into probate in New York and her estate was valued at $367,000. Miss Rambova lived in New Milford Conneticut in her later years. However, her immediate family moved her out to California due to ill health. She was the adopted daughter of perfume mogul Richard Hudnut to whom her mother was married to. The will lists 25 specific bequests, left a $200 monthly lifetime pension to her half-sister Mrs. Mary Boyd, San Francisco and the balance of the estate went to 11 other relatives. One personal bequest left her entire library and collection of Tibetian and Nepalese Paintings and Bronzes to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

There was something about the new dances that were being introduced to the public. It was these very dances that made this country’s melting pot sizzle. In New York City, there were famous places employing male dancers who catered to women and their preoccupation with pleasure of being in a man’s arms and enjoying an afternoon of lighthearted flirting. There was something of a paradigm shift and a change in standards of acceptable public behavior for woman. For the times they lived in it was quite liberating for women calling all the shots. One newspaper editorial talked about woman swooning in the embraces of the male dancers and their dutiful husbands were working hard. So why couldn’t men move from behind the counter or desk and take their rightful place on the dance floor and make anywhere from $30.00 to $100.00 a week? The movie industry wanted to capitalize on the dance craze, and this was about to occur on a grand scale. In 1921, “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”, an epic melodrama became the biggest box office hit of the 1920’s.

Transformations of the Picturesque The world was dancing Paris had succumbed to the mad rhythm of the Argentine tango. – The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921)

The movies leading star, Rudolph Valentino became a household name. To women the world over he became “a romantic symbol of the modern age”. Famous Players- Lasky realized the silent movie idol’s appeal to women and immediately capitalized on the frantic publicity. Valentino was a former paid dance companion and exhibition dancer. “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” has different dance scenes that capitalize on the social repercussions when two people dance suggestively. The New York World Newspaper’s movie review wrote that Valentino was well chosen for his leading role. The part calls for an adept dancer of the Argentine tango and he was the type needed for the part. The film was a complex family centered narrative with amazing special effects. The box office advertising you cannot have known how the tango can be danced until you see “The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse”. When Valentino appears in his first movie scene dressed in a gaucho outfit puffing on a cigarette while he stares suggestively at a female dance in a Buenos Aires Dance Hall, this stirs the imaginations of woman movie goers. Then Valentino glides with his partner across the dance floor in the sensuous moves of the tango but the effect is amazing. Julio his male beauty and sex appeal showing his dance partner he is the master of her body in the tango’s controversial hot hip contact. A master of seduction he moves on to his next conquest Marguerite Laurier, an attractive married woman. Their affair starts in a Parisian tango palace and on the dance floor he impresses her with his charm and grace. Then on to his art studio, Julio crushes his lover in a romantic embrace and his hands are all over her body in places one would not normally see on a movie screen. Alas all good things must come to an end and the affair is discovered and Julio must atone for his sexual transgressions. The start of WWI, Julio realizes his love for Marguerite, but he has a greater responsibility and a noble cause to his country. Julio dies on a muddy battlefield and both his family and lover mourn his loss. After this movie release, magazine articles were publishing articles about dancing with Valentino is an ultimate fantasy. For example, Movie Picture World Magazine article “When Valentino Taught Me to Dance” author Mary Winship gives a first-person account. She said “his arm supported me like a brace, I swum myself back, closed my eyes, breathed in the music and followed his movies. The music stopped, Valentino applauded and was so sweet. In 1922, Motion Picture Magazine, published an article “The Perfect Lover”, described Valentino as suave, debonair, with a glistening courtesy alien and disarming. After this article was published, he advised readers to “first dismiss the idea of me being sleek and elegant”. In the same year, another studio magazine Screenland talks about the problems with Valentino’s former profession. Valentino could make a good living as a dancer though he does not like it as a profession. His real qualifications as a landscaper are where he should earn his living. There is doubt whether he could earn a living outside of a studio or a dance hall. Valentino was woman made as a professional dancer since he partnered with already established female dancers. June Mathis described by fan magazines as a maker of young men was besieged by other young Valentino like men who constantly obtrude themselves into her home, imploring to be made with conscientiously amorous eyes. The role of dance in determining Valentino’s popularity was most forcefully illustrated when Valentino walked out on his contract with Famous Players-Lasky. In 1923, Valentino and his second wife Natacha Rambova, a trained ballet dancer, embarked on a successful dance exhibition tour under the sponsorship of Mineralava Beauty Company. In 1924 magazine poll, Valentino being named the fourth most popular dancer in the United States. Valentino’s legal problems with Famous Players Laskey were eventually resolved and he was able to go back to work. In 1925, two movies, “Cobra” and “Eagle” premiered, and Valentino’s moves are dance-like with refinement and grace. Both were not a box office success, but it still cemented his status as fan favorite. In January 1926, Valentino was interviewed for Collier’s Magazine. In the interview dance is portrayed as the last resort of an immigrant’s honest attempts to make a living. The star recounts falling back on his dance talents after he has pursued other jobs such as ‘”polishing brass, sweeping out stores, anything that will put a roof over my head and food in my stomach.” He is quoted as saying of his film career: “I wanted to make a lot of money, and so I let them play me up as a lounge lizard, a soft, handsome devil whose only aim in lite was to sit around and be admired by women. But at the same time, all I am a farmer at heart. In October 1926, The Dance Magazine, satirically declared Hollywood was the heaven of opportunity “where good dancers go when they die.”. Valentino’s sudden death of peritonitis five weeks before the magazine’s appearance demonstrated a deep if no doubt unintended irony in that statement. Death would not end the debate over Valentino’s symbolic place within the perceived crisis in American sexual and gender relation. Valentino, like dance, had become symbolic of social changes, taking place in the system governing American sexual relations in a post Victorian country. Valentino had confronted the country with other uncertainties as well. While some of these gender-based uncertainties converged with those offered by other matinee idols, such as John Barrymore, Valentino presented a higher order of problematics that circulated around the convergence of female fantasy with the dangerous, transformative possibilities of dance and with the highly restrictive norms

From September 1923 issue of Pictures and Picturegoer Fan Magazine. Valentino sails to London for a vacation and naturally a moving going public would like to know more about their favourite idol.

This is not an answer to the question “why do girls leave home,” but an attempt to analyse Rudolph Valentino, the screen’s most popular lover. This London interview, with the beloved Rudolph gives you an unconventional pen-picture of the man whose charm has been described as “irresistible” by feminine picturegoers all the world over. Once upon a time there was a man named Job who had a pretty rough passage through this vale of tears. Job, as you remember, was a patient man. Sarcastic women will tell you that he is the only patient man in the history of the world. I disagree. In my time I have met a large number of patient men, but without any hesitation I award the palm of patience to a man I met to-day. His name is Rudolph Valentino. When a celebrity comes to London, journalists foregather in his vicinity like flies round a honeypot. If he is good “copy,” he has to stand and deliver. There is no escape. Clever people can dodge bloodhounds and it is possible to deceive a policeman; but the copy-hound will get you every time. In a reception room on the first floor at the Carlton Hotel, Rudolph Valentino entirely surrounded by copy-hounds. I recognised the old familiar bark: “And what do you think of England and the English people?” before the door opened to admit me into the presence of the man who rules the raves. A moment later I was shaking hands with a dark man of strikingly handsome aspect, who wore a magnificent dressing-gown over purple pyjamas, and sported rings on his fingers and red Russian-leather slippers on his toes. There is no denying that the man is devilish good looking, but if he carries the conceit that usually goes with good looks he dissembles very cleverly. For he is quiet and shy and sensible and as you shall learn hereafter, he is about the most patient thing that ever happened. For three days and nights life for Valentino had been one question after another. Yet when I met him on the fourth day of his visit he was as bland and smiling as the man who says, “Yes, we have no bananas.” But the burden of Rudolph’s song was, “No, I can’t tell you anything about London. I haven’t seen it yet and then where have you been” I inquired. “Here,” said Rudolph Valentino. “Here in this hotel answering questions, the telephone, or letters. I have had to engage a secretary to assist with the correspondence it is more than one person can handle. See that pile there? Girls write and say: “Please may I come and see you and bring mother and father. Now what “Ting-a-ling! “He hasn’t had a minute’s peace, said Personal Representative Robert Florey, a very tall and very polite young Frenchman. “He came here for a holiday, and “Of course, I am delighted with all your kindness, ” said Rudolph Valentino, returning from the phone. “It is splendid of you to give such a reception to a foreigner. Now if only A new journalist stepped into the room, crossed the floor and fixed Rudolph with a glittering eye. Tell me, “What do you think of London? And do you like the English girls?” Rudolph Valentino still smiled. “Yes, I am on a holiday,” he told me when we got together again five minutes later. “A few days in London, then Paris, and then a motor trip to Nice. Afterwards I am going to my home after an absence of ten years. It will be Ting-a-ling! Rudolph Valentino lifted the telephone receiver with one hand and held out the other to the latest visitant from the Street of Ink. “Very pleased to meet you, Mr. Valentino,” said the new arrival. “How do you like London, and what do you think of the English people?” Some minutes afterwards I got Rudolph into a corner and asked him to autograph some pictures for me. I noticed that he signed himself Rudolph Valentino. I suppose he ought to know, but most people spell its Rodolph or Rodolf these days. “I owe my introduction to the movies to Norman Kerry,” he told me. We shared a flat together during my dancing days. He taught me a lot about America, and it was on his advice that I tried for a film engagement. At first, I played a number of minor roles. One of my early pictures were “Out of Luck” with Dorothy Gish, but I was not at home in comedy. Being a distinct Latin type I did not shine in American roles, and I did not get a real chance until “The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.” As Julio I “Excuse me, Mr. Valentino,” broke in Robert Florey at this juncture. “This gentleman from the ‘Weekly Guzzle’ would like to meet you.” How are you, Mr. Valentino?” said the gentleman from the “Weekly Guzzle.” “I suppose you will be settling down in London by now. How do you like it? And what do you think of the English people?” Sometime afterwards Valentino told me: “I was in New York when I received a telegram from Rex Ingram and June Mathis asking if I would go to Hollywood to play the part of Julio Desnoyers in “The Four Horsemen.” I telegraphed an acceptance and set out for the Coast at once. It was June Mathis, the scenarist who recommended me for the role, and the telegram was the turning point in my career. I worked very hard because I made up my mind to succeed now that my chance had come. Apart from my acting I helped Mr. Ingram to direct the big crowd scenes and I coached the crowds in the tango palace episodes. I tried . . .”Ting-a-ling! After the interval, I tried to get Valentino to talk about the ladies. The man who has fluttered more feminine hearts than any hero of the age should be worth listening to on this subject. But all he would tell me was: “A woman is always a woman, whether she wears a straw skirt or a Paquin gown. “Maybe that is why Rudolph is loved by the ladies from Kew to Katmandu. The screen’s most perfect lover understands feminine psychology. In between telephone calls and visitations, Rudolph told me something of his early career. When he arrived in New York at the age of eighteen, he could speak very little English and for some time he had a very rough passage as a stranger in a strange land. His first job in America was as a landscape gardener, but it didn’t last long enough to yield him any tangible benefit. So being something of a tango expert he set out to make a living as a professional dancer. He made a living all right, but there was nothing luxurious about it. Indeed, for many months Rudolph was perilously near starvation on more than one occasion. After dancing his way along the road to fame without getting any appreciably nearer to his goal, Rodolph started again as an actor. This time he travelled some distance, all the way to Salt Lake City with a touring company in fact–but the show went bust, and, with it, Rudolph’s hopes. In 1917 played his first speaking part, when he appeared with Richard Dix in a play called “Nobody Home.” Still success refused to smile upon him, and after trying in vain to enlist in the Italian, Canadian and British armies, Rudolph began to think that fortune had a grudge against him. There followed a period of hard-luck days before Rudolph took his first chance with the movies. Some of his earlier picture efforts were “The Married Virgin,” “The Delicious Little Devil” (with Mae Murray), “Eyes of Youth” (with Clara Kimball Young), “Ambition” (with Dorothy Phillips) and “The Cheater” (with May Allison). Most of all, Rudolph Valentino hates to be looked upon as a lounge lizard type of man. He is debonair to a degree, but there is nothing effeminate about him. Amongst other things he is a skilled horseman and is looking forward to hunting in this country later in the year. The above brief sketch of Rudolph’s career will show you that he has known a good deal of the seamy side of life. Although he made a record jump from the bottom of Fame’s ladder, the success he enjoys to-day is by way of compensation for his sufferings of yesterday. Most people, when their luck changes so rapidly, put on airs and lose their mental balance. People who have known Rudolph from the beginnings of his screen career assert that he hasn’t changed at all, which is a pretty high tribute to his strength of character. Wherein lies the secret of Rudolph’s wonderful power over the hearts of film fans. I have but put the question to a number of feminine friends and all returned different answers. “He looks so thoroughly wicked,” one told me. “He is so adorably handsome,” said another. “He is a wonderful actor, and that’s why,” explained a third, whilst a fourth murmured mysteriously: “It’s his eyes!” Rudolph’s eyes are of very dark brown, and his raven hair fairly gleams in the light. His complexion is swarthy, and he has a well-knit frame suggestive of strength. He speaks in a very quiet musical voice with very little trace of a foreign accent. He is neither voluble nor given to gesture, and during the time I was with him he betrayed no traces of excitement. The phone bell rang with steady persistency every other minute, and eager interviewers filed in and out to ask him what he thought of London. But Rudolph came through it all with a smiling face. His patience seemed inexhaustible. Rudolph Valentino hopes to be back in movie harness again by the autumn when his legal battles will be settled. Rudolph is out to raise the standard of the movies for he holds that screen art is being ruined by commercialism at the present time. “The right to strike” applies to screen stars in Valentino’s opinion, and so he struck. He gave me a scathing denunciation of the methods of American moviemakers. “There is graft all the way through,” said Rudolph, “and it is graft that helps to destroy artistic effect. Here’s just one example. The art or technical director in the production of a photoplay selects the costumes, settings and the properties, that is to say, he creates the atmosphere for the picture. A scene, for example, that calls for a Louis XVI setting demands furniture and other decorations of that period. Selecting and arranging these articles is the work of the art director. These properties are rented from firms who make a specialty of that business. “Now producing companies’ managers frequently form a combination with these rental firms, which work out in this way when a picture is made. The technical directors are given a list of stores from which they are compelled to make their art selections, regardless of whether the proper goods are obtainable in them. If a Louis XVI setting is desired, perhaps one couch or chair of that particular period can be found in the favoured stores. Selections cannot be made from firms other than those on the list and manufacture of them is out of the question, because of the cost. The art directors go to the manager in dismay, and he says, “Use anything, what does the public know about it?” Their alibi is always that the public cannot tell the difference anyway. The secret is that the listed stores charge the producers double rental prices, one-half of which goes to the grafting manager. “If a rug of particular pattern could be rented at a store not on the list for twenty dollars, a rug of much less value to the picture would have to be selected at a listed store for fifty dollars, the difference going to graft. There is no freedom anywhere. The men who head the different departments under the art director, such as the electricians, carpenters, etc., all artists in their line, are frequently replaced by others with no qualifications, but who are friends of the manager, his wife’s brother, or his Cousin Willie, and so on.” At this juncture Valentino was called away to the telephone again, and I prepared to take my leave. “I’m sorry we were interrupted so often,” he told me at parting. “We must meet again for a quiet chat. Don’t forget to tell the English picturegoers how grateful I am to them for their reception of myself.” On my way down the stairs, I met a man who looked uncommonly like a journalist. “Is that Mr. Valentino’s room?” he asked. I acquiesced and stood for a moment whilst the inquirer vanished through the doorway. In that moment I heard a mellow voice beginning: “Tell me, what do you think of London, and” Like Pontius Pilate, I paused not for the answer. I knew it already. Also, I know that I am backing Rudolph Valentino for the Patience Stakes. I reckon he can give Job a couple of stone and lose him over any distance.

I recently came across a made for television “movie” that I had not seen before and thought I would watch it and provide a review. This is a heavily fictionized story of silent film actor Rudolph Valentino, and Metro Pictures screen writer June Mathis. June Mathis is finishing the script for “The Four Horsemen” and Valentino was caught robbing her home. It was then, she realized the potential this young man had to become a great actor. Through her mentorship June guides her discovery into becoming one of the screens most gifted actors of his time.

The movie’s casting players were all wrong for the roles they played. For example, Franco Nero was a bad choice for the starring role in playing Valentino. Both his look, mannerisms and speech are over dramatic and exaggerated. Susanne Pleshette’s look for the movie was too glamourous and nothing like June Mathis. While she was semi-believable the make-up artists and wardrobe needed to downplay her appearance into a more semblance of what June Mathis might have looked like. Both Yvette Mimieux as Natacha Rambova and Alicia Bond as Nazimova are not even close to the original stars.

I read the original reviews of this made for television trash and I agree this is one that should have never been made a complete waste of both time and money.

Valentino and his fellow Italians celebrated the Christmas holidays during the 1920’s. The 1920’s was a time where globally everyone was still recovering from a world war that took many lives and reeked devastation everywhere. Yet a new century was in full swing and it was still a time where the traditional family unit gathered around the table each night and observed the Sabbath each Sunday. Holidays were a time in life where relatives gathered together during the holiday season to remember and reflect on the true meaning of Christmas and celebrate together with joy. People from all walks of life coming as one upholding traditions passed down thru the generations.

Hollywood a community globally looked on with awe and the Christmas holidays, comes to a city filled with flaming red poinsettias, manicured green lawns, electric lighted Christmas trees. Beautifully decorated streetlamp posts with tinsel decorations and glitter festooned store fronts to let visitors and local citizens alike the holiday season has arrived. Major movie film studio cars, chauffeured town cars, and taxi cabs alike rushing around delivering flowers, baskets of food, beautifully wrapped packages from address to another. These same movie film studios are sending Christmas cards from their favourite star to the fans and newspaper writers who support the industry, all year long. Also, there are the industries workers to consider from the prop boy, hairdresser, tailor, secretaries, grip boys whose valuable contribution to the film making industry. Silent film stars like Lila Lee, Leatrice Joy, Nita Naldi, Buster Keaton, Monte Blue, Gloria Swanson, Mary Miles Minter, Ricardo Cortez, Harold Lloyd, Rudolph Valentino and his wife, Ramon Navarro, Lupe Velez, will gather with their respective family and friends to celebrate in a most festive way. Rudolph Valentino’s family and Natacha Rambova’s family are in Europe wrapped up cozy warm in front of the respective fires celebrating in their own ways. While our couple are remaining in California due to film commitments and a wave of homesickness in the air. They felt Christmas should traditionally be spent where they would put a fire in the fireplace to roast nuts and cook a meal together. Rudy would thoughtfully present Natacha with a new jewel or another dog to add to their growing menagerie. The day would end with them reading poetry to each other and discuss their plans for the upcoming year. However, Rudy would often think about his family back home and miss the wintry weather, mulled wine, and the rich dinner. This was a time of celebrating and the evening would see the churches packed with people looking forward to altars bathed in candlelight and voices joyously singing songs willed with meaning. Sometimes Rudy would take a drive down to Palm Springs dessert where the nights were genuinely like those near Bethlehem where once upon a time, three Wise Men would follow a star. On the other side of the world, Italians would celebrate the Christmas season starting with 8 December with the feast of Immaculate Conception and end on 6 January with the feast of Epiphany. Their trees would be quietly decorated with cherished ornaments passed down through the family and the base of the tree would feature a nativity scene. Italians are a traditional people, and their Christmas eve meal would not have meat and of course a lavish dessert of Christmas cake or Panettone is served. An old saying goes “Christmas with your family and Easter with anyone you wish.” The most characteristic Italian Christmas sound is the one of bagpipes, played by pipers called zampognari. Stockings would be filled with fruit and simply carved toys for children and the adults would exchange home-made gifts. Times with family had special meaning and there was a festive spirit that was in everyone. A courteous greeting was extended to all while the New Year was looked upon with a certain relief it was a simple time where family and friends were more important.

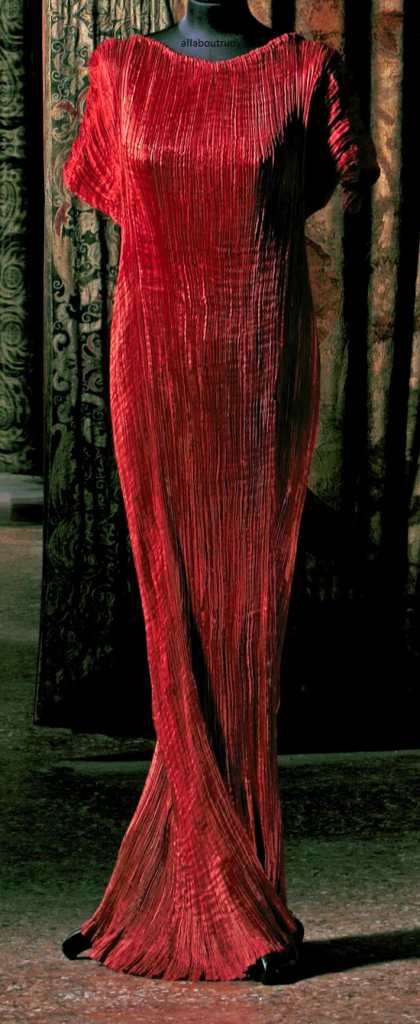

In 1924, Natacha wore a Fortuny Delphos dress. These two pictures show both the colored version and the black/white version of the dress.

Newlin & Ashburn and Gwyn Redwine, both of Los Angeles, for appellant. Scarborough & Bowen and McGee & Sumner, all of Los Angeles, for respondent Bank of America National Trust & Savings Ass’n.

Appeals were taken from an order of the probate court settling the account current and report of the executor and from an order denying a petition for partial distribution. Both appeals are presented on the same typewritten transcripts.

Rodolpho Guglielmi, also known as Rudolph Valentino, a motion picture actor, died testate August 23, 1926. On October 13, 1926, the appellant herein was appointed executor, and thereupon entered upon the administration of his estate. The pertinent portions of the decedent’s will, which was duly admitted to probate, provide:

“First: I hereby revoke all former Wills by me made and I hereby nominate and appoint S. George Ullman of the city of Los Angeles, County of Los Angeles, State of California, the executor of this my last will and testament, Without bonds, either upon qualifying or in any stage of the settlement of my said estate.

“Second: I direct that my Executor pay all of my just debts and funeral expenses, as soon as may be practicable after my death.

“Third: I give, devise and bequeath unto my wife, Natacha Rambova, also known as Natacha Guglielmi, the sum of One Dollar ($1.00), it being my intention, desire and will that she receive this sum and no more.

“Fourth: All the residue and remainder of my estate, both real and personal, I give, devise and bequeath unto S. George Ullman, of the city of Los Angeles, County of Los Angeles, State of California, to have and to hold the same in trust and for the use of Alberto Guglielmi, Maria Guglielmi and Teresa Werner, the purposes of the aforesaid trust are as follows: to hold, manage, and control the said trust property and estate: to keep the same invested and productive as far as possible; to receive the rents and profits therefrom, and to pay over the net income derived therefrom to the said Alberto Guglielmi, Maria Guglielmi and Teresa Werner, as I have this day instructed him; to finally distribute the said trust estate according to my wish and will, as I have this day instructed him.”

The instructions referred to in paragraph 4 of the will are as follows:

“To S. George Ullman.

“I have this day named you as executor in my last will and testament; it is my desire that you perpetuate my name in the picture industry by continuing the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., until my nephew Jean shall have reached the age of 25 years; in the meantime to make motion pictures, using your own judgment as to numbers and kind, keeping control of any pictures made, if possible.

“Whenever there are profits from pictures made by the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., it is my wish that you will pay to my brother Alberto the sum of $400.00 monthly, to my sister Maria the sum of $200.00 monthly, and to my dear friend Mrs. Werner the sum of $200.00 monthly.

“When my nephew Jean reaches the age of 25 years, I desire that the residue, if any, be given to him. In the event of his death then the residue shall be distributed equally to my sister Maria and my brother Alberto.

“Rodolpho Guglielmi

“Rudolph Valentino.”

In due time the probate court decided that these instructions were made contemporaneously with the will and became a part of the execution of the will, also that the will and the instructions taken together constituted the full terms of the trust created by the will.

Notice to creditors was given, and all claims were paid or settled or had become barred when the account was filed. The inventory and appraisal filed April 13, 1927, showed real and personal property amounting to $244,033.15. A supplementary inventory and appraisal filed January 9, 1928, showed additional real and personal property amounting to $244,550 or a total estate of over $488,000.

On February 28, 1928, appellant filed his first account as executor, to which objections were made by Alberto Guglielmi and Maria Guglielmi Strada, the brother and sister of deceased. Proceedings for the settlement of this account were abandoned. On April 5, 1930, appellant filed a new first account to which objections were made by the same parties, but were not heard. On June 7, 1930, appellant filed his resignation as executor, which was accepted, and the respondent Bank of America was appointed administrator with the will annexed. On August 18, 1930, appellant filed a supplemental account, to which the administrator filed objections, including the objections made by the brother and sister to the former accounts. These accounts, with the objections of the administrator and of these heirs, came on for hearing on November 5, 1930, and on August 8, 1932, the probate court made the decree from which this appeal is taken.

In the course of this hearing, the question arose as to the legality of advances made by appellant to the brother and sister of the deceased and to another beneficiary of the will, and, on the suggestion of the court, a petition for partial distribution was filed by the administrator. On the hearing of that petition, the probate court found that the decedent left surviving him as his only heirs at law Alberto Guglielmi and Maria Guglielmi Strada; that the only persons entitled to benefit from the trust created by the will were said heirs, Teresa Werner, and Jean Guglielmi; that the questions relative to the advances made to three of the above beneficiaries were determined by the decree settling the account entered contemporaneously with this account; and that, because of the condition of the estate, no partial distribution should be decreed.

During his lifetime the decedent had been engaged in various activities in addition to his work as an actor. He was interested in the production and development of pictures under the corporate name of Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., which, however, was but an alter ego. He was engaged in the exploitation of chemical discoveries under the corporate name of Cosmic Arts, Inc. He was also sole owner of a cleaning business under the name of Ritz, Inc. In March, 1925, decedent made a contract with a motion picture producer under which he agreed to give his services as a motion picture actor to that producer exclusively. In April, 1925, he assigned his interest in the profits under this contract to Cosmic Arts, Inc. In August, 1925, Cosmic Arts, Inc., assigned its interest in this contract to Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc. The stockholders in Cosmic Arts, Inc., were the decedent, Natacha Rambova, his wife, and Teresa Werner, his wife’s aunt. Though these three corporations were separate entities, the decedent for a long time prior to his death conducted the affairs of all three under the ostensible name of Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., making all expenditures through the latter, with little regard for the corporate identity of the other two concerns. During this period, the appellant served in the capacity of business manager and personal representative of the decedent; superintendent of Ritz, Inc.; secretary, treasurer, and director of Cosmic Arts, Inc.; and manager of Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., his compensation for all these services being paid by Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc.

Immediately upon his qualification as executor, and acting upon the asserted authority of the will to continue the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., for the purpose of perpetuating the name of deceased, the appellant entered upon the management of all these concerns in the same manner in which they had been conducted in the lifetime of the decedent. In these transactions the appellant, seemingly acting as the executor of the estate rather than as trustee under the will, paid all claims outstanding against the decedent, personal as well as those incurred by the corporations mentioned. The exact figures covering these expenditures are not material to this inquiry, but the appellant emphasizes the fact that as executor he took an estate which was heavily involved financially and practically bankrupt, and through his management all indebtedness was cleared and the property of the estate was increased in value to $890,000.

In the course of the conduct of these activities, the appellant borrowed and loaned money, executed mortgages and retired existing liens, purchased new property to be used in the business, and sold property belonging to the estate. To obtain publicity to aid in the display of the decedent’s pictures, two spectacular funerals were held––one in New York and one in Los Angeles––and Valentino Memorial Clubs were organized in many different centers. Because of the financial condition of the estate at the time, these expenditures were paid largely from money borrowed by the executor on his personal obligations, and all, or nearly all, were made without an order of court. When funds accumulated through the distribution of pictures, the appellant made loans, some with security and some without. In September, 1927, he loaned one Mae Murray $22,000 at 7 per cent. In March, 1928, he loaned the Pan American Company $50,000 at seven per cent., secured by Pan American Bank stock of the then value of $78,000; at various times during the year 1928 he loaned one Frank Menillo $40,000 at 8 per cent. The Murray loan was repaid. The Pan American loan was compromised at a loss of $16,000 to the estate, with which amount appellant was charged to account with interest on the full amount of the loan. The Menillo loan was unpaid at the time of the entry of the decree herein, and appellant was charged to account in full with interest.

The ruling of the probate court on these two items presents the principal ground of attack upon the decree. If appellant was authorized to carry on the business of the decedent, to invest and reinvest the funds in his hands, then any losses arising from these transactions must be borne by the estate. If he was not so authorized, the losses are his. The question of the right of an executor to carry on the business of the deceased when so directed by the testator first came directly before our appellate courts in Estate of Ward. 127 Cal. App. 347, 15 P.(2d) 901, a case which was decided after the decree herein was entered. In that case Judge Ames, sitting pro tempore in the appellate court, carefully reviewed the authorities, and concluded that, in the absence of fraud or mismanagement, an executor should not be charged with losses while he is following out the instructions of the testator. Numerous authorities from other jurisdictions are cited by Judge Ames, to which reference may be had in that opinion. This distinction between the two cases should be noted––here all these loans were made from profits of the estate accumulated by the executor; in the Ward Case the losses were in the principal. The conclusions there reached compel a reversal of the decree as to the Pan American and Menillo loans because they were attacked on the sole ground that they were made without order of court or without “sufficient” surety, but were not attacked upon any charge of fraud or mismanagement.

The dual capacity of the executor and trustee involved in this appeal is the same as that considered in the Ward estate, where the court, after reviewing authorities on that subject, held that, taking the will as a whole, it could not have been the intention of the testator to suspend operations of the business during the period of time required for the administration of the estate and the appointment of a trustee. The case here is even stronger than the will interpreted in the Ward Case, because the instructions of the testator to the trustee are so blended and mingled that they could scarcely be separated the one from the other. The directions to the executor to “perpetuate my name in the picture industry by continuing the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc.,” and the directions, to the trustee “to hold, manage, and control the said trust, property, and estate; to keep the same invested and productive as far as possible,” disclose an intention of the testator to treat the executor and trustee without the legal distinction that a court would draw between the two offices.

For these reasons we conclude that the executor was both authorized and directed by the will to carry on the business of the decedent as it had been carried on in his lifetime, and that the investments made by him through loans to the Pan American Company and to Menillo were made in the course of the operation of that business, and, being without fraud, the appellant should not be charged for the losses occurring therefrom, nor should he be surcharged with interest on account of any investments made in his management of the estate.

The probate court charged appellant with an item of $17,280.19 expended by him in compliance with a contract of Cosmic Arts, Inc. This item presents an issue closely related to that just discussed. Cosmic Arts, Inc., was a family corporation organized by the deceased. Ten shares of stock were issued, all in the name of Natacha Rambova, the then wife of the decedent. One of these shares was transferred to her aunt, another to the decedent, and the three were the directors. Decedent resigned from the directorship and had the appellant appointed in his place. While the latter was acting as director and treasurer of the corporation and under the authority of the by–laws, he executed a contract with one Lambert obligating the corporation to bear any and all expenses in connection with the patenting, sale, and exploitation of patents covering a chemical discovery called Lambertite. For a considerable period prior to his death, the affairs of this corporation were conducted by the decedent as his alter ego, acting through the appellant as his personal manager in very much the same manner as the affairs of the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., were conducted. The contract referred to was apparently ratified by the corporation, and the expenses of the corporation were paid by the decedent, not only in connection with the patenting of the process, but in the conduct of the laboratory in New York City for the development of the process. Upon his qualification as executor the appellant continued to pay these expenses, amounting to a total of over $19,000 and so accounted to the estate. In the hearing of the objections to this item, the appellant contended that the entire stock of the corporation had been transferred to the decedent through a property settlement made at the time of the separation with his wife, but the separation agreement was not produced. The contract with Lambert was received in evidence, and from this the probate court found that Cosmic Arts, Inc., was entitled to one–third of the profits resulting from the sale and exploitation of the patents, and that therefore it was liable for but one–third of the expenses incurred in the patenting, sale, and exploitation of the process. Upon this theory it was concluded that the decedent and his estate were liable for but one–ninth of these expenses, basing this conclusion solely upon the theory that Cosmic Arts, Inc., was a family corporation organized by the decedent, his wife, and his wife’s aunt, in which the decedent had a one–third interest.

The evidence on this issue is in such an unsatisfactory state that it is impossible at this time to determine the issue. It is manifest that it was tried by the probate court without the benefit of the decision in the Ward Case, and that, if the facts justify the contention of the appellant that Cosmic Arts, Inc., was also an alter ego of the decedent, the business of which appellant was authorized by the will to carry on under the will, then such losses incurred by appellant in the operation of that business as may be found to have been incurred without fraud or mismanagement must, under the rule of the Ward Case, be held to be the losses of the estate and not of the appellant. For these reasons this issue should be retried.

Appellant, complains of the ruling of the probate court surcharging him with interest on the full amount of moneys withdrawn by him on account of his fees for extraordinary services in advance of an order of court authorizing any fee for such services. The evidence discloses that during his period of administration the appellant withdrew from the funds of the estate sums aggregating $22,300, for which he asked credit in the settlement of his account upon the basis of extraordinary services rendered the estate. The probate court disallowed the item and charged appellant to account for interest at the rate of 7 per cent. from the time of each withdrawal. It then allowed the appellant an additional fee for extraordinary services fixed at $15,000. The appellant now argues that this sum should be subtracted from the total amount withdrawn, and that he should be charged to return to the estate the difference, amounting to $7,300, and should be charged interest on that amount only. Authorities cited by the appellant relating to statutory fees to which an executor is entitled as matter of right do not apply to a case of this kind. Extraordinary fees are allowed an executor within the discretion of the probate court, and, unless and until an order is made, there is no obligation on the part of the estate to pay more than the statutory fees. Hence, when an executor upon his own motion withdraws the funds of an estate to pay himself fees in addition to the amount allowed by statute, he is to be charged with the amount thereof, with interest thereon from the date of withdrawal. Estate of Piercy, 168 Cal. 755, 757, 145 P. 91.

It is next contended that the court erred in holding the appellant liable for the advances to the brother and sister of the decedent and to Teresa Werner on account of what he deemed to be their distributive shares of the estate. The court found in its decree settling the account that the executor improperly and without authority or order of court advanced to decedent’s brother over $37,000 out of the funds and property of the estate; to the decedent’s sister over $12,000 in cash and personal property; to Teresa Werner over $7,000 in cash; and to Frank A. Menillo at various times and in various amounts an aggregate sum of $9,100. Having ruled during the hearing on the settlement of the account that it was not competent for the court in that proceeding to determine questions of heirship, and having directed a special proceeding to be instituted for that purpose, the court, contemporaneously with the entry of its decree in the settlement of the account, entered its decree in the other proceeding wherein it was found that the brother and sister were the only surviving heirs at law of the decedent, and that the only persons entitled to benefit under the will were the brother, the sister, Teresa Werner, a stranger, and Jean Guglielmi, a nephew of decedent. It will be recalled that under the terms of the instructions the brother, the sister, and Mrs. Werner were each to receive a stipulated sum monthly until the nephew, Jean, reached the age of 25 years, when the residue was directed to be given to him; that, in the event of the death of the nephew, the residue was to be distributed equally between the brother and sister. It is apparent from these provisions of the will that Teresa Werner was entitled to participate in the assets of the estate only to the extent of a monthly payment out of profits which the executor derived from pictures made under his direction, and that the brother and sister were entitled to a distributive share in the estate only in the event of the death of the nephew, Jean. It necessarily follows that advancements made to these individuals in excess of the monthly payments directed by the will were improper. The appellant does not question this final result, but does criticize the method by which the court expressed its conclusion. In its decree in the proceeding for partial distribution, it declared the issues relative to these advances had been determined by its decree correcting and settling the account of the executor, and that by reason of the foregoing decree said advances “are hereby declared to be void and improper and chargeable to said executor herein.” It is true, as argued by the appellant, that the issue covering the propriety of advances on distributive shares is not one which may be determined on a hearing of a settlement of the executor’s account, but that such issue can be determined only upon a hearing for distribution, partial or final. 12 Cal. Jur. 181. We are not, however, in accord with appellant’s view that the court was in error so far as it went. Though reference is made in its decree to the order settling the account, there is sufficient in the decree denying distribution to constitute a determination that these advances were void and improper and as such chargeable to the executor.

There are certain equities involved in this issue which require comment. In the will proper, which was admitted to probate in October, 1926, the executor was directed to hold all the property in trust “to keep the same invested and productive as far as possible and to pay over the net income derived therefrom” to Alberto and Maria Guglielmi and to Teresa Werner. Four years later, the appellant, in answer to the petition for partial distribution, came into court and for the first time set forth a copy of the written instructions which he alleged had been executed contemporaneously with the execution of the will and which he alleged had been lost, destroyed, or surreptitiously removed from the personal effects and safe of the decedent. In the decree entered in that proceeding the probate court found this to be a true copy of the original instructions executed by the decedent, and declared that said instructions should be taken together as the complete terms of the trust created by the will. Under the terms of these instructions, the appellant was directed to pay to Alberto Guglielmi $400 a month, to Maria Guglielmi $200 a month, and to Mrs. Werner $200 a month out of the “profits from pictures made by the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc.” Then for the first time the nephew, Jean, is mentioned, and to him is given the entire residue when he reaches the age of 25 years. This is followed by the proviso that in the event of his death the residue should be distributed equally to Alberto and Maria. It will be noted that under the terms of the will proper the appellant was directed to pay over to Alberto and Maria and to Mrs. Werner the net income derived from the estate as a whole, whereas under the terms of the written instructions he was directed to pay stipulated amounts monthly to each of the three from profits from pictures made by the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc. It does not appear from the record who was responsible for the loss of the written instructions following the decedent’s death nor whether the appellant had any information or knowledge of their terms prior to the advancements he made to these three. It does appear that all these advances were made with the consent and at the solicitation of the three beneficiaries involved. We are in accord with the holding of the probate court that these advances were improperly made if the terms of the written instructions are held to be controlling over the terms of the fourth paragraph of the will proper and if these advances are held to have been made from funds other than the net income derived from the estate as a whole. Under the rule of Estate of Willey, 140 Cal. 238, 73 P. 998, this is an issue which cannot be tried or determined in the proceeding for the settlement of the account, but is one which could have been determined on the proceeding for partial distribution. The proper practice is as outlined in the Willey Case to retire from the consideration of the settlement of the account the question of the propriety of advances of distributive shares so that that question can be determined on distribution of the estate. The record on the petition for distribution does not disclose that this question was fully tried and determined. Manifestly, if these three beneficiaries were entitled to the net income derived from the management of the estate as a whole, and if the advances made to them by the appellant were from that net income alone, he should not be charged to account to the estate in full for those advances or for interest as if he had defaulted or misapplied the funds to his own use. On the other hand, if, upon final distribution, it be found that the nephew is dead and that the brother and sister are then entitled under the will to the entire residue, then the amounts advanced to them by the appellant may be held to have been advanced on account of their distributive shares, and appellant would be entitled to a credit accordingly. These considerations were undoubtedly in the contemplation of the probate court when, in rendering its decree denying partial distribution, it found that it was unable to determine whether there would be sufficient funds or property to distribute to the trustee or to permit the trust to be executed and performed, and for that reason reserved its determination of the ultimate practicability of the trust until the final distribution of the estate. But, in any event, if these advances were made in good faith and at the solicitation of the beneficiaries, and appellant is held to be accountable to the estate in full therefor, he should be given an appropriate lien against the beneficial interest of those who participated in the advancement of the property and funds of the estate. In re Moore, 96 Cal. 522, 31 P. 584; Finnerty v. Pennie, 100 Cal. 404, 407, 34 P. 869; Estate of Schluter, 209 Cal. 286, 289, 286 P. 1008.

Though the appellant has not assigned any special error for the reversal of the order denying partial distribution, the equities herein referred to impel a reversal, so that both matters may be before the probate court for new proceedings consistent with the views herein expressed.

The orders appealed from are both reversed.

NOURSE, Presiding Justice.

We concur: STURTEVANT, J.; SPENCE, J.

Ten years ago, Rudolph Valentino died in New York City at the age of 31. Today he lies in a borrowed crypt and his fortune whittled down to nothing. The three women in his life are living successful lives of their own. His first wife Jean Acker is in Hollywood, substituting for a movie role in Camille vacated by the illness of Adrienne Matzenpauer and still using his name as a means of making money. His second wife, Natacha Rambova, living in Palma Mallorca and is a wife of a Spanish nobleman. The third woman Pola Negri who at the time of his death, announced to the world she was his fiancé and went on to marry a fake Prince.

The fortune he had at one time was estimated by friends at $2,000,000 was found to be in reality next to nothing. His manager said, “he was always in debt”. In 1932, a court appraisal showed $400,000 had been paid out in monetary claims against the estate had dwindled that amount down significantly. Yet Rudolph Valentino at the time was the highest paid actor. Joseph Schenck chairman of United Artists said Valentino earned $1,000,000 in the year, before his death and spent it lavishly on jewelry, paintings, travels, and horses. When he started out, he was early $5.00 a day as an extra. In 1926, he was under contract at $200,000 for two movies a year, plus one fourth of a producer fee a gross income from his pictures more than the value of his salary.

In London, there is a Rudolph Valentino Memorial Association which from time to time inserts obituary notices about him in the newspapers and supports a roof top garden named after him. In June of this year, buyers paid $23 for the contents of three trunks he left in Turin, Italy he left in 1925. They contained old clothes. Roger Peterson manager of Cathedral Mausoleum says from time to time complains to police people are chipping marble off the Valentino crypt. A few women still come occasionally to pray and leave flowers, he said recently, and one visits the tomb regularly and her name is Jean Acker. Mr. Peterson is talking about writing a book.

You must be logged in to post a comment.