Posts Tagged With: Rudolph Valentino

1916 – Aimee Crocker and Senor Rudolpho

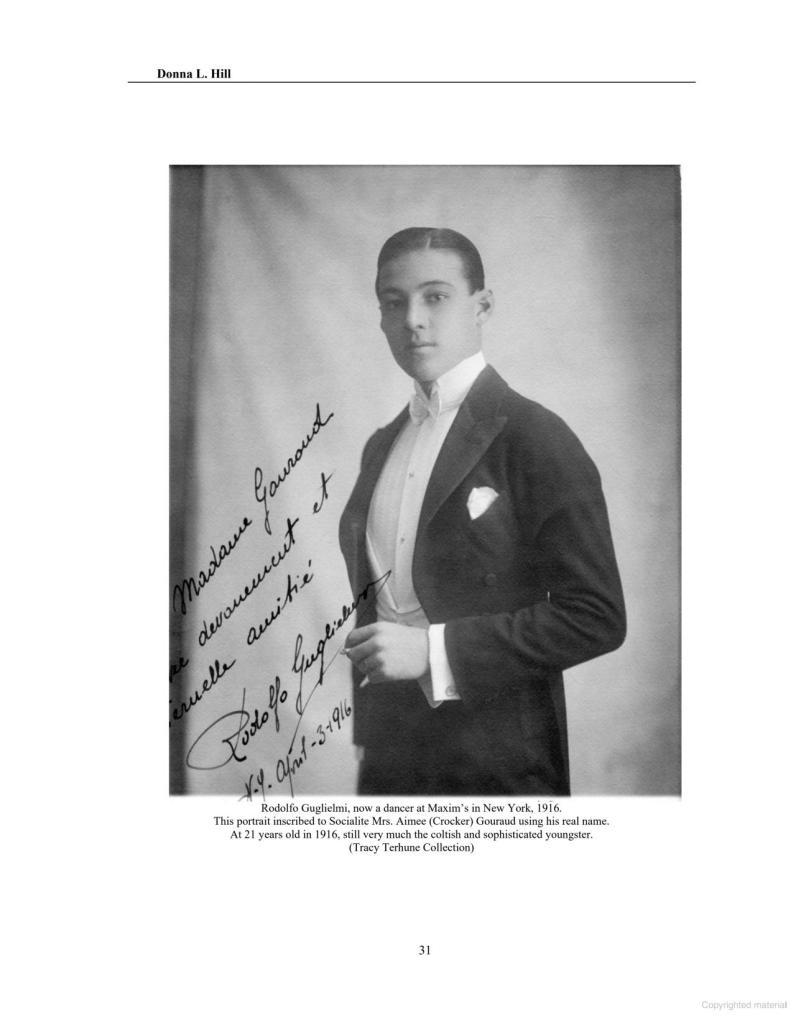

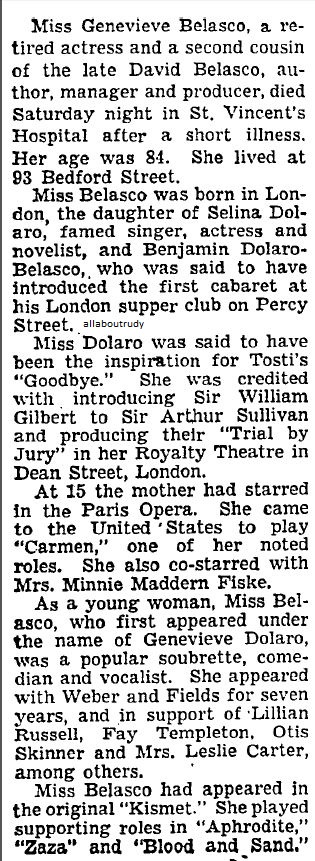

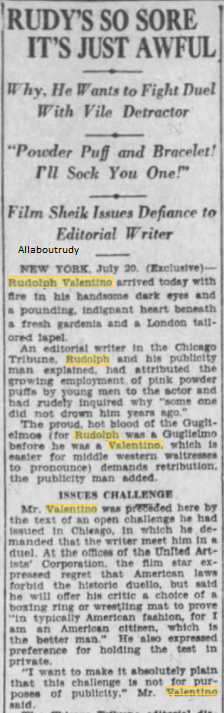

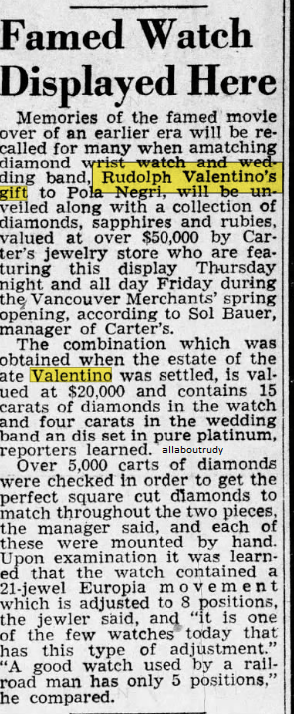

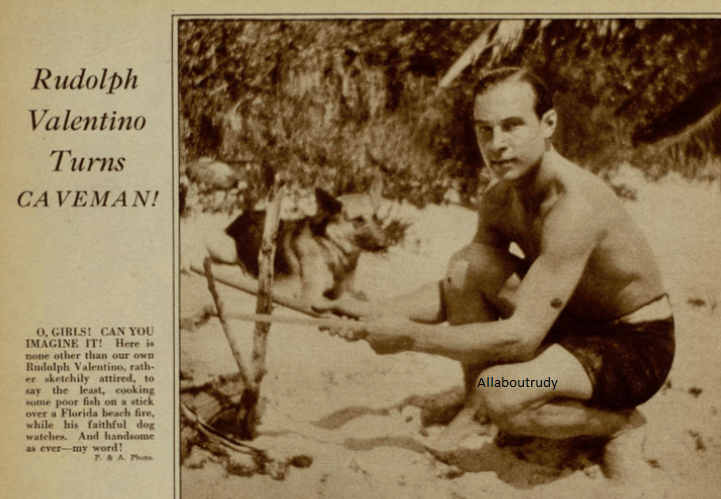

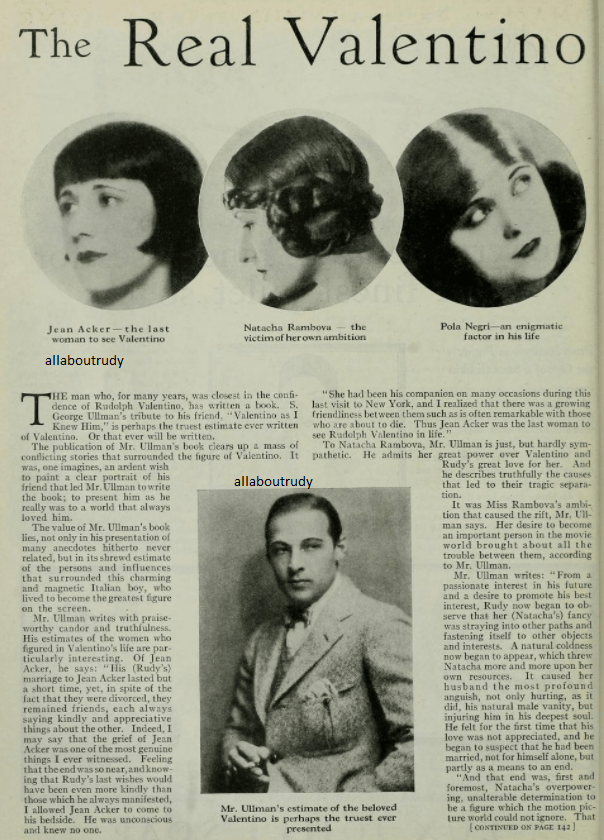

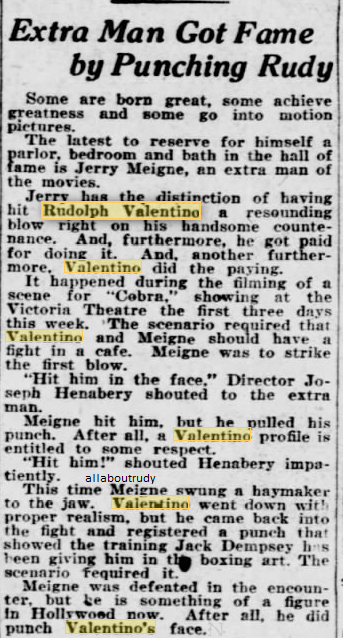

Aimee Crocker was born in 1864, Sacramento, California to parents who came from privileged backgrounds and scandalous headlines seemed to be an inherited trait. When Aimee became older, she seemed to attract attention wherever she went. When New York City became the epic center for the rich and powerful our young lady became a true socialite. She was young, rich, two dangerous combinations. A true Gilded Age beauty in New York City high society. She socialized with the upper 400 hundred and was friends with society matrons of the day such as Mamie Fish, Caroline Webster Schermerhorn, Tessie Oelrich and Alva Vanderbilt Belmont. However, the Gilded Age was struggling to survive and yet Aimee somehow managed to make local gossip headlines with her antics. Aimee had no need to worry about money. However, for poor immigrants newly arrived to Ellis Island for a chance at the American dream. One of these immigrants eventually became famous in his own right but success would take time for Rudolph Valentino to achieve. As a young immigrant who could not speak English, he realized that in order to become successful he needed to make connections, get a job, learn English and survive in anyway he could. A born survivor and dreamer, he found his way to work at the world-famous Maxim’s de Paris. This restaurant was expensive and everything was done on a grand scale that they were noted for. Julius Keller, proprietor of Maxims knew that rich Americans savored a European Continental style atmosphere, and they introduced a ballroom that offered dancing with paid dancers and music. To attract a certain clientele, it was important to hire young and handsome men who knew how to dance and treat and cater to a paying public. Eventually Valentino found work there and often gave “private dance lessons” and soon became a local favourite. One of these such fans Aimee would become known for participating in private dance lessons in one of the rooms set aside. Eventually she would let it publicly be known he was her protégé’. However, as time went by Valentino would make his way to California and the rest is a true Hollywood story.

Reference:

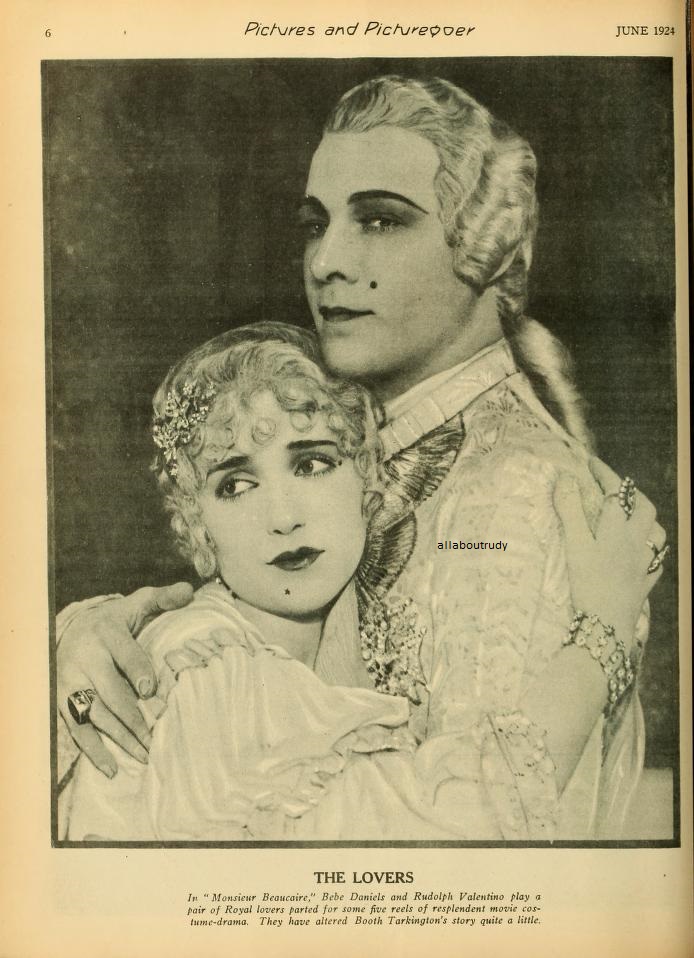

Photo is courtesy of Tracy Terhune Collection

28 May 1988 – Valentino Press Agent

21 May 1956 – Man Buys Valentino Chair in Hollywood Hotel Auction

Mark (Lucky) Marlatt, ice cream salesman, decided to pop into an ongoing auction of furniture at the old Hollywood Hotel. He paid $12.00 for two chairs silent film star Rudolph Valentino once sat in. He asked he auctioneer “Do you mind if I sell a little ice cream while I am here”? Within minutes he was doing a thriving business in the hotel lobby. The hotel will be soon torn down and I will have those chairs paid for in no time and it turns out he was right. He made enough money to buy them.

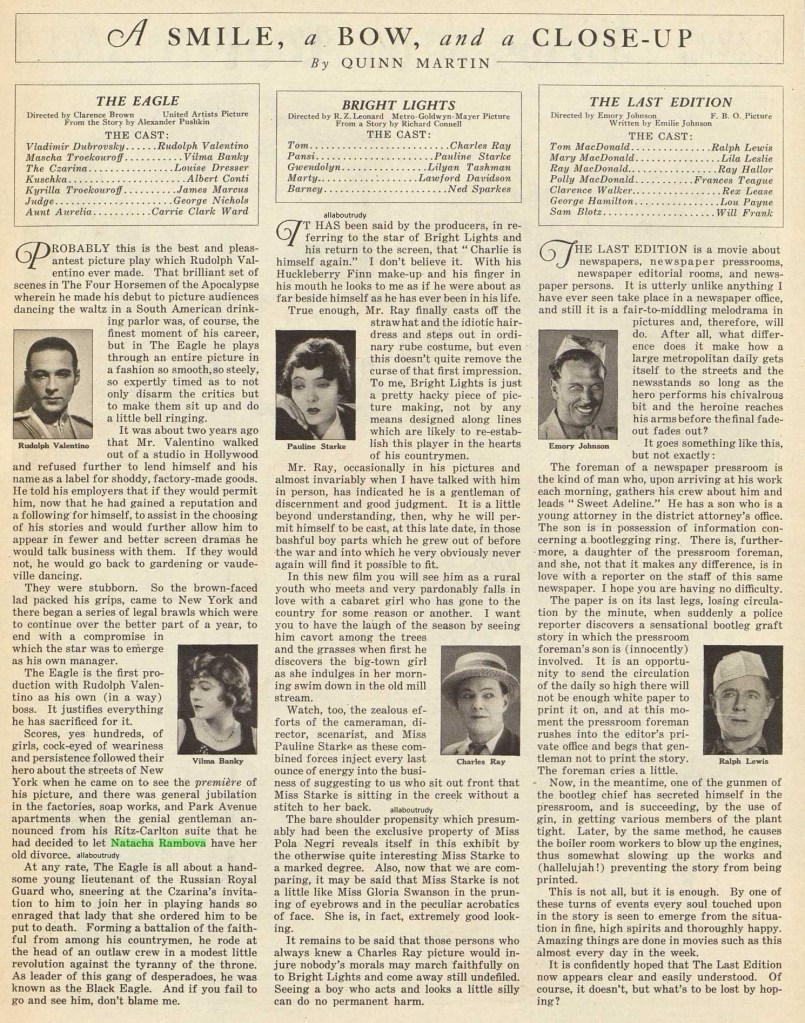

May 1923 – WHAT’S the MATTER with the MOVIES? by RUDOLPH VALENTINO

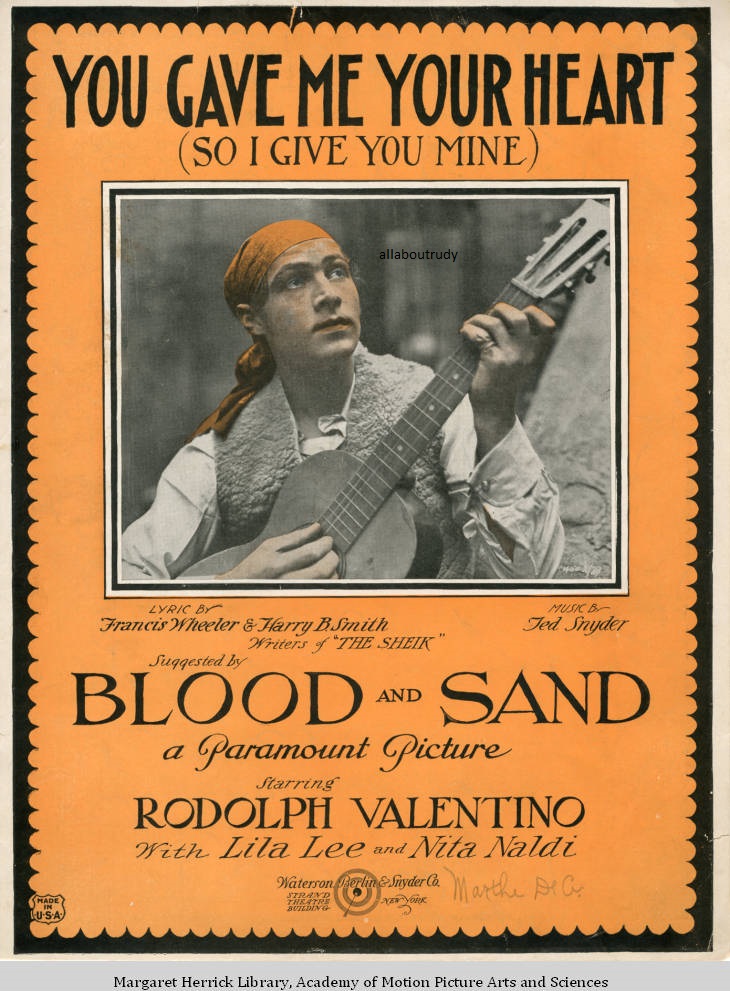

There is nothing the matter with the movies that cannot be remedied. This is indeed fortunate–for the movie has earned an important place in the life of the American public. No one will deny that motion pictures have been helpful, instructive, and entertaining. No one doubts that they can be a great influence for good–or evil. And everyone knows they are too big to be ignored. They have assumed such importance as to incur a proportionate responsibility. And yet those entrusted with their development choose to close their eyes to the writing on the wall. The principal trouble with the motion picture today is that it is an industry, not an art. It has been too highly commercialized for its own good. Of course, the businessperson is necessary to the motion picture, but not to the exclusion of the artist. It is right and good that Fords and locomotives and adding machines and safety razors and lead pencils shall be standardized and turned out according to hard and fast specifications–and that quantity production shall cut down overhead. It is also good business that the distributing station be standardized and handle the usual full line of equipment at standard prices. But those methods are bad medicine for motion pictures. The film made to the dollar-ruled specification, turned out on a quantity production basis, added to the cut-and-dried program, and then released throughout the trust-controlled theatres is, without doubt, a specimen of efficient industrial production–but as an artistic entertainment it is a sad failure. No one doubts that pictures can be produced under this highly efficient business method much cheaper and faster than by the old “hit-or-miss” artistic way–and that these pictures can net their producers and distributors a much larger return per dollar invested than those handicapped by artistic requirements. But, after all, what are you spending your money in your local moving-picture theatre for? To see artistic, fascinating pictures or to build fortunes for those in control of the industry? There the heart of the problem is exposed–the average motion picture is made to fatten purses, not to entertain the public. Commercial motion pictures have their rightful usage, as have also less artistic films of entertainment, just the same as commercial art has its proper place, and commercial music and jazz, and advertising and cheap vaudeville and burlesque. But how would you like to discover the powers that be insisting that you must take your art and your music and your literature “according to our program.” Suppose you went to the Grand Opera and heard a little factory-produced opera, then a little jazz and then a half hour of song “plugging” flavored with ten minutes of Galli-Curci or Chaliapin singing a nursery rhyme. Or suppose when you purchased a set of Shakespeare you found every other page devoted to advertising or publicity writing or that your evening to Ethel Barrymore was four-fifths taken up by an act of cheap melodrama, a little burlesque, a bit from the minstral and an acrobatic squad. Suppose that when you attempted to buy pictures for your home you discovered they could only be shown in connection with commercial drawings. Yet you get just about such a hodgepodge when you attend a motion picture theatre running trust-controlled programs. And with the trust growing stronger every day the independent exhibitor is being driven farther and farther into the corner. All of which is very fine for efficiency and profit, but very bad for art and entertainment. In my opinion, 75 per cent of the pictures shown today are a brazen insult to the public’s intelligence. The other 25 per cent are produced by such experts as D. W. Griffith, Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, the Talmadge interests–and a few other independent stars and producers who realize that the making of pictures is an art, not an industry. Such splendid features as “Broken Blossoms,” “Way Down East,” “Tolerable [sic] David,” “Little Lord Fauntleroy,” “Robin Hood,” “The Kid,” “When Knighthood was in Flower,” along with a few other productions which rank among these, have invariably been received in such a way as to prove that the American public wants and appreciates artistic productions. The next thing to do is demand them. The public always gets what it _demands_. All of these pictures were produced by independent companies who loathe to follow the factory cut-and-dried methods perfected by the picture trusts. The various stars and directors who have fought and dared to produce films of real merit are keeping faith with you in spite of the handicaps they face. They are courageously battling the interests that are monopolizing not only the production but the exhibition of motion pictures. They deserve your unqualified support. The only hope for the future of the moving picture lies with them. Support them and you will enjoy pictures made by conscientious producers, from real stories, pictures in which the artists have an opportunity to give you the best they have. Under the present system the actor is treated like a factory hand–is driven helter-skelter through a picture by a director who is afraid of the slave-driving studio manager who, in turn is spurred to increased production by producers. And these producers have but a single motive–profit. Such producers established themselves by imitating, in a superficial and insincere way, the artistic productions of D. W. Griffith, Mary Pickford and others by cashing in on their creative genius. Then they were merely parasites. Now they are infinitely worse. Instead of merely imitating, they are attempting to crush the conscientious producer. And their method of crushing is efficient–as is every other business scheme they have worked out. The blade with which they are trying to knife the producer of artistic pictures cuts two ways. First it hamstrings him and then it cuts off his lines of distribution. Process No. 1 is to discredit the stars that work with him and at the same time reduce to a minimum the value of the production on which he is working. The most efficient way to discredit stars is to make them common–to belittle their work; to prevent them from expressing their own interpretation of art; to compel them to perform poorly. Name over to yourself a dozen of your favorite stars. When you think of moving picture stars you think of them. Now suppose that eight of that dozen were hired by powerful syndicates and put to work on cheap pictures. Suppose that the pictures they made were weak and their work was unconvincing. Suppose each of them made four pictures, or even six or ten pictures, to every picture one of the other four made. In other words, suppose that of every ten pictures featuring your favorite stars nine were weak and and the stars’ work most disappointing. Wouldn’t you begin to feel that, after all, it was not the star but the picture that counted? And the method of discrediting artistic feature pictures is as simple. D. W. Griffith produces a marvelous spectacle–the work of countless months of time and the genius of true artists. It impresses you mightily. You must see the next spectacle of that kind when it is released. So, the “industrial” producers figure. Before D. W. Griffith can produce another masterpiece, they flood the theatres with dozens of cheap imitations, each heralded as the peer of Griffith’s best work. So grossly are they misrepresented, so flagrantly are they mis-advertised and so miserably do they fall below your expectations that you naturally “swear off” spectacles for the rest of your life. “Who suffers?” The conscientious producer. No matter how good it may be his next production is almost guaranteed a failure, now. Meanwhile the imitator flits to the next artistic production and proceeds to copy it, cheaply. In doing so he shackles a star to a weak part and then rushes him through the picture, thus, killing two birds with one stone. For the public feels it has been hoodwinked by stars and features. As real stars and real productions are all the independent producer with the conscience has to offer, he suffers once again. Do you wonder then that a moving-picture actor whose hope? for the future lies in his work of today repudiates an unfair contract rather than be a party to the ruination of good pictures? That is why I have refused to work for picture butchers at $7,000 a week on cut-and-dried program features and have offered to return to work for twelve hundred and fifty dollars a week if a competent, conscientious director directs my work in worth-while features. The trusts method of curtailing the independent producer’s distribution is also very efficient. This is accomplished through its distributing mediums. Again, we find its methods twofold. They sell complete programs, a trick by which the small exhibitor must show a whole year of their pictures in order to get any at all–and then he must take the whole program, just as it is turned out of the mills. The other method is to secure interest or ownership in theatres and permit them to show only trust pictures. So, it is not always the fault of the exhibitor who runs the theatre you patronize if the ordinary program pictures you see day in, and day out are not up to your expectations. He is not to blame any more than is the artist who appears in the picture you take exception to. The poor exhibitor, in order to secure a few good pictures with box-office value, is forced to sign the trust’s entire output for the year. And so, he must contract to rent eighty-two or more pictures, though he knows full well that some will be so impossible he will have to refrain from showing them and simply pocket his loss. That is what is the matter with the movies–and that is why the American public spent only one half as much on pictures last year as they did the year before. And that is why they will spend even less next year if something is not done to remedy the situation. The American public wants good pictures and is entitled to them. The conscientious producers want to produce good pictures and should be supported in doing it. The real artist-actor wants to give you the best there is in him. In order to do this, he must be allowed to act in high-grade pictures and take sufficient time to make them. Art is the only weapon with which the conscientious producer and the artist, or star, can fight the commercialism of the trust producers. Naturally, the trust wants to discredit art and lower the public’s idea of what the standard of pictures should be. The lower the standards, the cheaper the pictures can be made, the lower the overhead, the more the profit. Now you can understand why Rudolph Valentino is not making pictures. The merciless cutting of “Blood and Sand” threw me into grave doubts. My experience in “The Young Rajah” verified my fears. I realized that I was not going to be permitted to act in real pictures or give the necessary time and study to me work. Art? What did that mean to the commercial producers? They wanted film–thousands of feet of film. And they wanted it quickly. The quicker the film was made the less the overhead, and the sooner the release. So, we hurried through. Night after night we worked–sometimes until daylight. We actually finished the picture August 10, at three in the morning. Apparently, those producers were convinced that midnight oil is conducive to genius. I’m not going to hurry through any more pictures, and I’m not going to be cast to parts that are unworthy of a novice or a worn-out ham. Other movie actors have taken this stand. Some have fallen by the way. Some have emerged victorious–Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplin, the Talmadge girls, and now comes Harold Lloyd. Forget Valentino and his little squabble–but keep your eyes on the independent producers and on these stars. Compare them productions with those of trust-controlled producers. Remember that your money is the deciding vote whether the independent producer prospers and gives you real pictures or whether the trust monopolizes the whole industry and feeds you what profits it best. You are to be the judge. I know what your verdict will be. I have been asked why the producers so mercilessly hacked “Blood and Sand.” When the film was completed, it went to the business office. It was measured. It was too long–the most heinous offense known to the trust–a full six hundred feet too long. Its extra length meant a little less profit. So, to the butchering rooms it went. Of course, certain parts of it could be re-acted and condensed and thus keep the continuity clear. But that meant more time, more money, and less profit. So, clip, clip, clip. And the very heart of the film was cut out. How much that saved, I do not know, but it saved money. What if the public was a little confused and disappointed here? and there? The picture would get by. Everybody knew it was good. Why quibble about a scene or two? As a matter of fact, the picture was a lot stronger than it needed to be. And making pictures too good was simply piling up trouble for the future. It was spoiling the public. The better you give them the better they want. The thing to do was to standardize picture quality. Then they wouldn’t always be demanding the world and all for the price of one admission. With that philosophy in mind, they made “The Young Rajah”–and I quit. Maybe I’m temperamental because I refuse to caper through rot on the strength of what reputaion I may have earned. But this I know–the “Rajah” picture was the first step down. After that the descent would have been steady–and not so slow, either. Maybe, it is unbusinesslike to repudiate a contract that involves you in producing films in which you cannot possibly give the public what it is paying for, and in a process of cheapening that would mark one as a puppet rather than as an actor. If it is, then I’m unbusinesslike. It just happens that I have ideals–and hopes. I am sorry I ever acted in “The Young Rajah.” I will never act in another picture like it. The public wants art in pictures, and I believe I can put it there. Doug and Mary and Charlie and D. W. have done it and I’m going to try.

17 Apr 1934 – GUGLIELMI’S ESTATE. ULLMAN v. GUGLIELMI

District Court of Appeal, First District, Division 2, California. GUGLIELMI’S ESTATE. ULLMAN v. GUGLIELMI ET AL Civ. 9321.

Decided: April 17, 1934

Newlin & Ashburn and Gwyn Redwine, both of Los Angeles, for appellant. Scarborough & Bowen and McGee & Sumner, all of Los Angeles, for respondent Bank of America National Trust & Savings Ass’n.

Appeals were taken from an order of the probate court settling the account current and report of the executor and from an order denying a petition for partial distribution. Both appeals are presented on the same typewritten transcripts.

Rodolpho Guglielmi, also known as Rudolph Valentino, a motion picture actor, died testate August 23, 1926. On October 13, 1926, the appellant herein was appointed executor, and thereupon entered upon the administration of his estate. The pertinent portions of the decedent’s will, which was duly admitted to probate, provide:

“First: I hereby revoke all former Wills by me made and I hereby nominate and appoint S. George Ullman of the city of Los Angeles, County of Los Angeles, State of California, the executor of this my last will and testament, Without bonds, either upon qualifying or in any stage of the settlement of my said estate.

“Second: I direct that my Executor pay all of my just debts and funeral expenses, as soon as may be practicable after my death.

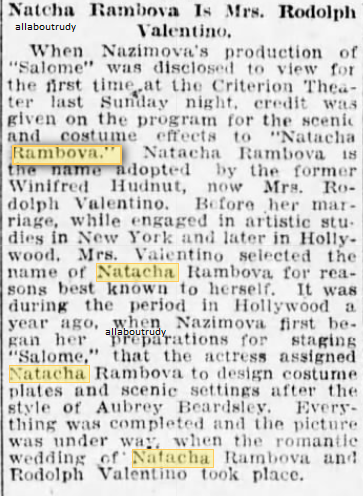

“Third: I give, devise and bequeath unto my wife, Natacha Rambova, also known as Natacha Guglielmi, the sum of One Dollar ($1.00), it being my intention, desire and will that she receive this sum and no more.

“Fourth: All the residue and remainder of my estate, both real and personal, I give, devise and bequeath unto S. George Ullman, of the city of Los Angeles, County of Los Angeles, State of California, to have and to hold the same in trust and for the use of Alberto Guglielmi, Maria Guglielmi and Teresa Werner, the purposes of the aforesaid trust are as follows: to hold, manage, and control the said trust property and estate: to keep the same invested and productive as far as possible; to receive the rents and profits therefrom, and to pay over the net income derived therefrom to the said Alberto Guglielmi, Maria Guglielmi and Teresa Werner, as I have this day instructed him; to finally distribute the said trust estate according to my wish and will, as I have this day instructed him.”

The instructions referred to in paragraph 4 of the will are as follows:

“To S. George Ullman.

“I have this day named you as executor in my last will and testament; it is my desire that you perpetuate my name in the picture industry by continuing the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., until my nephew Jean shall have reached the age of 25 years; in the meantime to make motion pictures, using your own judgment as to numbers and kind, keeping control of any pictures made, if possible.

“Whenever there are profits from pictures made by the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., it is my wish that you will pay to my brother Alberto the sum of $400.00 monthly, to my sister Maria the sum of $200.00 monthly, and to my dear friend Mrs. Werner the sum of $200.00 monthly.

“When my nephew Jean reaches the age of 25 years, I desire that the residue, if any, be given to him. In the event of his death then the residue shall be distributed equally to my sister Maria and my brother Alberto.

“Rodolpho Guglielmi

“Rudolph Valentino.”

In due time the probate court decided that these instructions were made contemporaneously with the will and became a part of the execution of the will, also that the will and the instructions taken together constituted the full terms of the trust created by the will.

Notice to creditors was given, and all claims were paid or settled or had become barred when the account was filed. The inventory and appraisal filed April 13, 1927, showed real and personal property amounting to $244,033.15. A supplementary inventory and appraisal filed January 9, 1928, showed additional real and personal property amounting to $244,550 or a total estate of over $488,000.

On February 28, 1928, appellant filed his first account as executor, to which objections were made by Alberto Guglielmi and Maria Guglielmi Strada, the brother and sister of deceased. Proceedings for the settlement of this account were abandoned. On April 5, 1930, appellant filed a new first account to which objections were made by the same parties, but were not heard. On June 7, 1930, appellant filed his resignation as executor, which was accepted, and the respondent Bank of America was appointed administrator with the will annexed. On August 18, 1930, appellant filed a supplemental account, to which the administrator filed objections, including the objections made by the brother and sister to the former accounts. These accounts, with the objections of the administrator and of these heirs, came on for hearing on November 5, 1930, and on August 8, 1932, the probate court made the decree from which this appeal is taken.

In the course of this hearing, the question arose as to the legality of advances made by appellant to the brother and sister of the deceased and to another beneficiary of the will, and, on the suggestion of the court, a petition for partial distribution was filed by the administrator. On the hearing of that petition, the probate court found that the decedent left surviving him as his only heirs at law Alberto Guglielmi and Maria Guglielmi Strada; that the only persons entitled to benefit from the trust created by the will were said heirs, Teresa Werner, and Jean Guglielmi; that the questions relative to the advances made to three of the above beneficiaries were determined by the decree settling the account entered contemporaneously with this account; and that, because of the condition of the estate, no partial distribution should be decreed.

During his lifetime the decedent had been engaged in various activities in addition to his work as an actor. He was interested in the production and development of pictures under the corporate name of Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., which, however, was but an alter ego. He was engaged in the exploitation of chemical discoveries under the corporate name of Cosmic Arts, Inc. He was also sole owner of a cleaning business under the name of Ritz, Inc. In March, 1925, decedent made a contract with a motion picture producer under which he agreed to give his services as a motion picture actor to that producer exclusively. In April, 1925, he assigned his interest in the profits under this contract to Cosmic Arts, Inc. In August, 1925, Cosmic Arts, Inc., assigned its interest in this contract to Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc. The stockholders in Cosmic Arts, Inc., were the decedent, Natacha Rambova, his wife, and Teresa Werner, his wife’s aunt. Though these three corporations were separate entities, the decedent for a long time prior to his death conducted the affairs of all three under the ostensible name of Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., making all expenditures through the latter, with little regard for the corporate identity of the other two concerns. During this period, the appellant served in the capacity of business manager and personal representative of the decedent; superintendent of Ritz, Inc.; secretary, treasurer, and director of Cosmic Arts, Inc.; and manager of Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., his compensation for all these services being paid by Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc.

Immediately upon his qualification as executor, and acting upon the asserted authority of the will to continue the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., for the purpose of perpetuating the name of deceased, the appellant entered upon the management of all these concerns in the same manner in which they had been conducted in the lifetime of the decedent. In these transactions the appellant, seemingly acting as the executor of the estate rather than as trustee under the will, paid all claims outstanding against the decedent, personal as well as those incurred by the corporations mentioned. The exact figures covering these expenditures are not material to this inquiry, but the appellant emphasizes the fact that as executor he took an estate which was heavily involved financially and practically bankrupt, and through his management all indebtedness was cleared and the property of the estate was increased in value to $890,000.

In the course of the conduct of these activities, the appellant borrowed and loaned money, executed mortgages and retired existing liens, purchased new property to be used in the business, and sold property belonging to the estate. To obtain publicity to aid in the display of the decedent’s pictures, two spectacular funerals were held––one in New York and one in Los Angeles––and Valentino Memorial Clubs were organized in many different centers. Because of the financial condition of the estate at the time, these expenditures were paid largely from money borrowed by the executor on his personal obligations, and all, or nearly all, were made without an order of court. When funds accumulated through the distribution of pictures, the appellant made loans, some with security and some without. In September, 1927, he loaned one Mae Murray $22,000 at 7 per cent. In March, 1928, he loaned the Pan American Company $50,000 at seven per cent., secured by Pan American Bank stock of the then value of $78,000; at various times during the year 1928 he loaned one Frank Menillo $40,000 at 8 per cent. The Murray loan was repaid. The Pan American loan was compromised at a loss of $16,000 to the estate, with which amount appellant was charged to account with interest on the full amount of the loan. The Menillo loan was unpaid at the time of the entry of the decree herein, and appellant was charged to account in full with interest.

The ruling of the probate court on these two items presents the principal ground of attack upon the decree. If appellant was authorized to carry on the business of the decedent, to invest and reinvest the funds in his hands, then any losses arising from these transactions must be borne by the estate. If he was not so authorized, the losses are his. The question of the right of an executor to carry on the business of the deceased when so directed by the testator first came directly before our appellate courts in Estate of Ward. 127 Cal. App. 347, 15 P.(2d) 901, a case which was decided after the decree herein was entered. In that case Judge Ames, sitting pro tempore in the appellate court, carefully reviewed the authorities, and concluded that, in the absence of fraud or mismanagement, an executor should not be charged with losses while he is following out the instructions of the testator. Numerous authorities from other jurisdictions are cited by Judge Ames, to which reference may be had in that opinion. This distinction between the two cases should be noted––here all these loans were made from profits of the estate accumulated by the executor; in the Ward Case the losses were in the principal. The conclusions there reached compel a reversal of the decree as to the Pan American and Menillo loans because they were attacked on the sole ground that they were made without order of court or without “sufficient” surety, but were not attacked upon any charge of fraud or mismanagement.

The dual capacity of the executor and trustee involved in this appeal is the same as that considered in the Ward estate, where the court, after reviewing authorities on that subject, held that, taking the will as a whole, it could not have been the intention of the testator to suspend operations of the business during the period of time required for the administration of the estate and the appointment of a trustee. The case here is even stronger than the will interpreted in the Ward Case, because the instructions of the testator to the trustee are so blended and mingled that they could scarcely be separated the one from the other. The directions to the executor to “perpetuate my name in the picture industry by continuing the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc.,” and the directions, to the trustee “to hold, manage, and control the said trust, property, and estate; to keep the same invested and productive as far as possible,” disclose an intention of the testator to treat the executor and trustee without the legal distinction that a court would draw between the two offices.

For these reasons we conclude that the executor was both authorized and directed by the will to carry on the business of the decedent as it had been carried on in his lifetime, and that the investments made by him through loans to the Pan American Company and to Menillo were made in the course of the operation of that business, and, being without fraud, the appellant should not be charged for the losses occurring therefrom, nor should he be surcharged with interest on account of any investments made in his management of the estate.

The probate court charged appellant with an item of $17,280.19 expended by him in compliance with a contract of Cosmic Arts, Inc. This item presents an issue closely related to that just discussed. Cosmic Arts, Inc., was a family corporation organized by the deceased. Ten shares of stock were issued, all in the name of Natacha Rambova, the then wife of the decedent. One of these shares was transferred to her aunt, another to the decedent, and the three were the directors. Decedent resigned from the directorship and had the appellant appointed in his place. While the latter was acting as director and treasurer of the corporation and under the authority of the by–laws, he executed a contract with one Lambert obligating the corporation to bear any and all expenses in connection with the patenting, sale, and exploitation of patents covering a chemical discovery called Lambertite. For a considerable period prior to his death, the affairs of this corporation were conducted by the decedent as his alter ego, acting through the appellant as his personal manager in very much the same manner as the affairs of the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc., were conducted. The contract referred to was apparently ratified by the corporation, and the expenses of the corporation were paid by the decedent, not only in connection with the patenting of the process, but in the conduct of the laboratory in New York City for the development of the process. Upon his qualification as executor the appellant continued to pay these expenses, amounting to a total of over $19,000 and so accounted to the estate. In the hearing of the objections to this item, the appellant contended that the entire stock of the corporation had been transferred to the decedent through a property settlement made at the time of the separation with his wife, but the separation agreement was not produced. The contract with Lambert was received in evidence, and from this the probate court found that Cosmic Arts, Inc., was entitled to one–third of the profits resulting from the sale and exploitation of the patents, and that therefore it was liable for but one–third of the expenses incurred in the patenting, sale, and exploitation of the process. Upon this theory it was concluded that the decedent and his estate were liable for but one–ninth of these expenses, basing this conclusion solely upon the theory that Cosmic Arts, Inc., was a family corporation organized by the decedent, his wife, and his wife’s aunt, in which the decedent had a one–third interest.

The evidence on this issue is in such an unsatisfactory state that it is impossible at this time to determine the issue. It is manifest that it was tried by the probate court without the benefit of the decision in the Ward Case, and that, if the facts justify the contention of the appellant that Cosmic Arts, Inc., was also an alter ego of the decedent, the business of which appellant was authorized by the will to carry on under the will, then such losses incurred by appellant in the operation of that business as may be found to have been incurred without fraud or mismanagement must, under the rule of the Ward Case, be held to be the losses of the estate and not of the appellant. For these reasons this issue should be retried.

Appellant, complains of the ruling of the probate court surcharging him with interest on the full amount of moneys withdrawn by him on account of his fees for extraordinary services in advance of an order of court authorizing any fee for such services. The evidence discloses that during his period of administration the appellant withdrew from the funds of the estate sums aggregating $22,300, for which he asked credit in the settlement of his account upon the basis of extraordinary services rendered the estate. The probate court disallowed the item and charged appellant to account for interest at the rate of 7 per cent. from the time of each withdrawal. It then allowed the appellant an additional fee for extraordinary services fixed at $15,000. The appellant now argues that this sum should be subtracted from the total amount withdrawn, and that he should be charged to return to the estate the difference, amounting to $7,300, and should be charged interest on that amount only. Authorities cited by the appellant relating to statutory fees to which an executor is entitled as matter of right do not apply to a case of this kind. Extraordinary fees are allowed an executor within the discretion of the probate court, and, unless and until an order is made, there is no obligation on the part of the estate to pay more than the statutory fees. Hence, when an executor upon his own motion withdraws the funds of an estate to pay himself fees in addition to the amount allowed by statute, he is to be charged with the amount thereof, with interest thereon from the date of withdrawal. Estate of Piercy, 168 Cal. 755, 757, 145 P. 91.

It is next contended that the court erred in holding the appellant liable for the advances to the brother and sister of the decedent and to Teresa Werner on account of what he deemed to be their distributive shares of the estate. The court found in its decree settling the account that the executor improperly and without authority or order of court advanced to decedent’s brother over $37,000 out of the funds and property of the estate; to the decedent’s sister over $12,000 in cash and personal property; to Teresa Werner over $7,000 in cash; and to Frank A. Menillo at various times and in various amounts an aggregate sum of $9,100. Having ruled during the hearing on the settlement of the account that it was not competent for the court in that proceeding to determine questions of heirship, and having directed a special proceeding to be instituted for that purpose, the court, contemporaneously with the entry of its decree in the settlement of the account, entered its decree in the other proceeding wherein it was found that the brother and sister were the only surviving heirs at law of the decedent, and that the only persons entitled to benefit under the will were the brother, the sister, Teresa Werner, a stranger, and Jean Guglielmi, a nephew of decedent. It will be recalled that under the terms of the instructions the brother, the sister, and Mrs. Werner were each to receive a stipulated sum monthly until the nephew, Jean, reached the age of 25 years, when the residue was directed to be given to him; that, in the event of the death of the nephew, the residue was to be distributed equally between the brother and sister. It is apparent from these provisions of the will that Teresa Werner was entitled to participate in the assets of the estate only to the extent of a monthly payment out of profits which the executor derived from pictures made under his direction, and that the brother and sister were entitled to a distributive share in the estate only in the event of the death of the nephew, Jean. It necessarily follows that advancements made to these individuals in excess of the monthly payments directed by the will were improper. The appellant does not question this final result, but does criticize the method by which the court expressed its conclusion. In its decree in the proceeding for partial distribution, it declared the issues relative to these advances had been determined by its decree correcting and settling the account of the executor, and that by reason of the foregoing decree said advances “are hereby declared to be void and improper and chargeable to said executor herein.” It is true, as argued by the appellant, that the issue covering the propriety of advances on distributive shares is not one which may be determined on a hearing of a settlement of the executor’s account, but that such issue can be determined only upon a hearing for distribution, partial or final. 12 Cal. Jur. 181. We are not, however, in accord with appellant’s view that the court was in error so far as it went. Though reference is made in its decree to the order settling the account, there is sufficient in the decree denying distribution to constitute a determination that these advances were void and improper and as such chargeable to the executor.

There are certain equities involved in this issue which require comment. In the will proper, which was admitted to probate in October, 1926, the executor was directed to hold all the property in trust “to keep the same invested and productive as far as possible and to pay over the net income derived therefrom” to Alberto and Maria Guglielmi and to Teresa Werner. Four years later, the appellant, in answer to the petition for partial distribution, came into court and for the first time set forth a copy of the written instructions which he alleged had been executed contemporaneously with the execution of the will and which he alleged had been lost, destroyed, or surreptitiously removed from the personal effects and safe of the decedent. In the decree entered in that proceeding the probate court found this to be a true copy of the original instructions executed by the decedent, and declared that said instructions should be taken together as the complete terms of the trust created by the will. Under the terms of these instructions, the appellant was directed to pay to Alberto Guglielmi $400 a month, to Maria Guglielmi $200 a month, and to Mrs. Werner $200 a month out of the “profits from pictures made by the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc.” Then for the first time the nephew, Jean, is mentioned, and to him is given the entire residue when he reaches the age of 25 years. This is followed by the proviso that in the event of his death the residue should be distributed equally to Alberto and Maria. It will be noted that under the terms of the will proper the appellant was directed to pay over to Alberto and Maria and to Mrs. Werner the net income derived from the estate as a whole, whereas under the terms of the written instructions he was directed to pay stipulated amounts monthly to each of the three from profits from pictures made by the Rudolph Valentino Productions, Inc. It does not appear from the record who was responsible for the loss of the written instructions following the decedent’s death nor whether the appellant had any information or knowledge of their terms prior to the advancements he made to these three. It does appear that all these advances were made with the consent and at the solicitation of the three beneficiaries involved. We are in accord with the holding of the probate court that these advances were improperly made if the terms of the written instructions are held to be controlling over the terms of the fourth paragraph of the will proper and if these advances are held to have been made from funds other than the net income derived from the estate as a whole. Under the rule of Estate of Willey, 140 Cal. 238, 73 P. 998, this is an issue which cannot be tried or determined in the proceeding for the settlement of the account, but is one which could have been determined on the proceeding for partial distribution. The proper practice is as outlined in the Willey Case to retire from the consideration of the settlement of the account the question of the propriety of advances of distributive shares so that that question can be determined on distribution of the estate. The record on the petition for distribution does not disclose that this question was fully tried and determined. Manifestly, if these three beneficiaries were entitled to the net income derived from the management of the estate as a whole, and if the advances made to them by the appellant were from that net income alone, he should not be charged to account to the estate in full for those advances or for interest as if he had defaulted or misapplied the funds to his own use. On the other hand, if, upon final distribution, it be found that the nephew is dead and that the brother and sister are then entitled under the will to the entire residue, then the amounts advanced to them by the appellant may be held to have been advanced on account of their distributive shares, and appellant would be entitled to a credit accordingly. These considerations were undoubtedly in the contemplation of the probate court when, in rendering its decree denying partial distribution, it found that it was unable to determine whether there would be sufficient funds or property to distribute to the trustee or to permit the trust to be executed and performed, and for that reason reserved its determination of the ultimate practicability of the trust until the final distribution of the estate. But, in any event, if these advances were made in good faith and at the solicitation of the beneficiaries, and appellant is held to be accountable to the estate in full therefor, he should be given an appropriate lien against the beneficial interest of those who participated in the advancement of the property and funds of the estate. In re Moore, 96 Cal. 522, 31 P. 584; Finnerty v. Pennie, 100 Cal. 404, 407, 34 P. 869; Estate of Schluter, 209 Cal. 286, 289, 286 P. 1008.

Though the appellant has not assigned any special error for the reversal of the order denying partial distribution, the equities herein referred to impel a reversal, so that both matters may be before the probate court for new proceedings consistent with the views herein expressed.

The orders appealed from are both reversed.

NOURSE, Presiding Justice.

We concur: STURTEVANT, J.; SPENCE, J.

11 Feb 1934 – Ullman Loses Suit

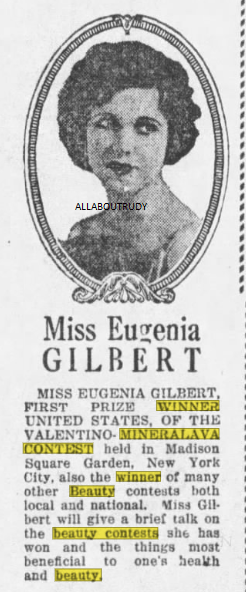

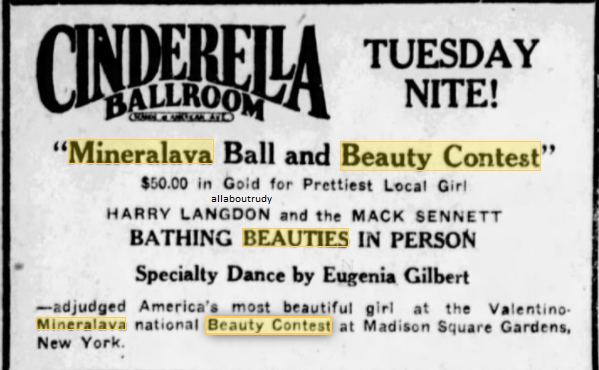

Feb 1924 – Mineralava Winner Update

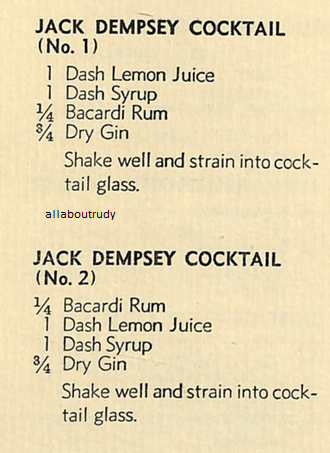

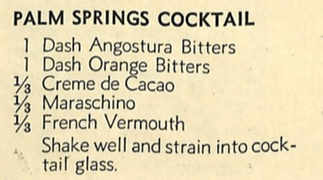

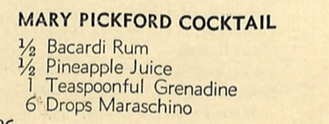

1920’s – Mixology

Since the Pandemic began a couple of years ago, there had been a phlethera of Old Hollywood Virtual Lectures with a portion dedicated to favorite Silent Film Stars cocktail receipes. I thought I would include a few that have not been featured anywhere else.

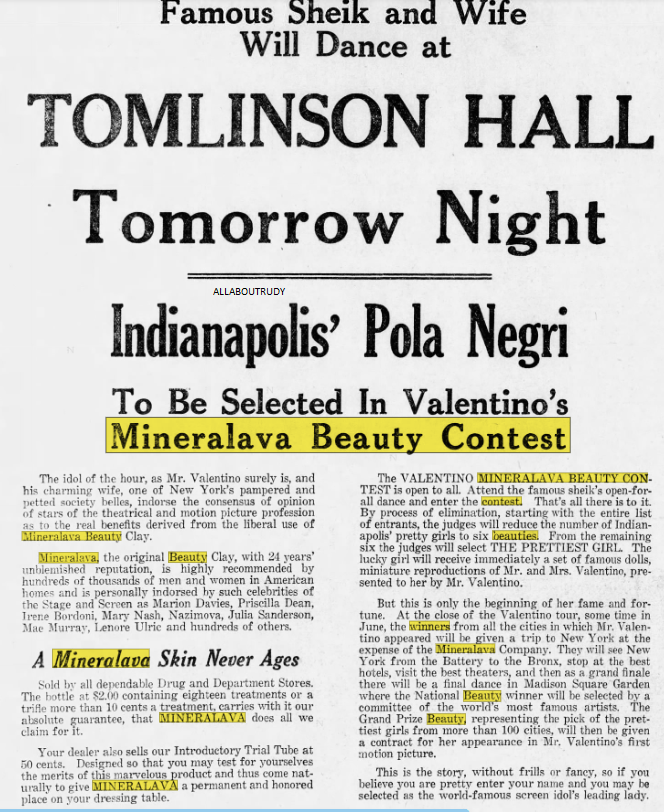

1 Jan 2024 – Mineralava Beauty Contest Continues

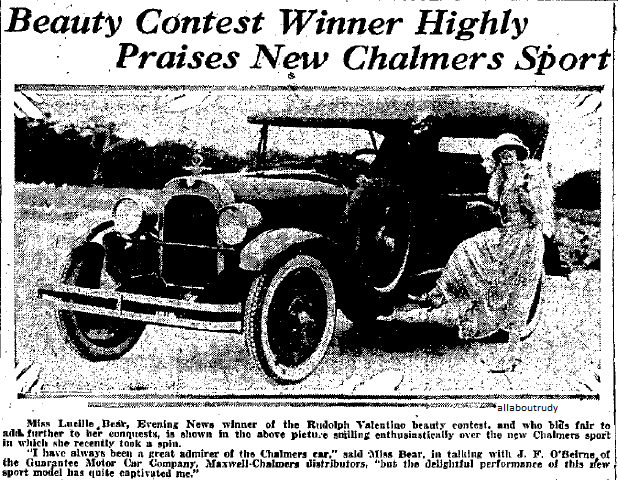

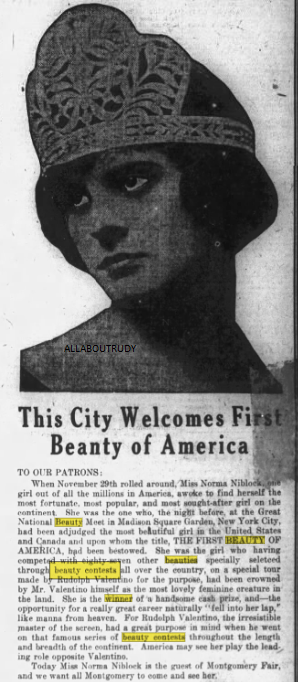

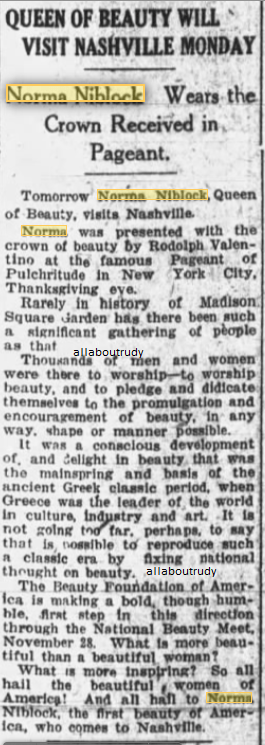

The month of January will be filled with continuing news articles on the Mineralava Beauty Contest. Contest winners were making local and national news in order to gather interest from the general public for potential movie career opportunities.

I want to take this opportunity to thank you and with you a Happy and Healthy New Year.

You must be logged in to post a comment.